HISTORY, like journalism and the law, lives largely on conflict and uncertainty. The historian is always poking into things to see just what was done, or not done - and if done, then how, where, when, by whom, and why. The evidence he has to examine is very uneven; some is good, some better, some is not so good, and some is no good at all. Much is contradictory, and more is incomplete.

The two little princes in the Tower are certainly dead; they were probably murdered, possibly by being smothered under their pillows, maybe at the order of their uncle Richard, maybe not. The Tudors, who took Richard's crown at Bosworth, may well have blackened his reputation. Shakespeare accepted their account, and made of it what everyone remembers. The Yorkists offer their arguments and the Tudors theirs. As yet neither has silenced the other.

So history never settles down. New evidence is always appearing; each generation thinks of new questions inspired by new experience. The method of reducing evidence to truth, Lord Acton said, is that "of common sense," and it is "best acquired by observing its use by the ablest men in every variety of intellectual employment," legal and scientific no less than historical.

The Rev. Mason Locke Weems wrote that George Washington, when about six years old, had killed his father's beautiful young cherry tree with his little hatchet and that when his father demanded to know what had happened, the boy, staggered for a moment by the question, had then looked up "with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth," and cried out: "I can't tell a lie, Pa; you know I can't tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet." In the course of time millions of persons read these noble words and accepted them; but historians suspected that when the Reverend Mr. Weems wrote them his face was less brightened with the charm of all-conquering truth than his small hero's had been. The sentiments quoted had a fishy sound. No citations were offered to support them and no authority but that of "an aged lady," unnamed. Honest departures from the truth seldom infuriate the historian unless they are excessively numerous, whereas evidence that has been concocted or colored or misconstrued arouses him to his highest pitch of accomplishment. Sooner or later, one hears the sound of something being punctured.

A far older fabrication is the so-called Donation of Constantine, produced a thousand years ago or more as evidence that temporal powers in the West had been resigned by the Emperor to the Pope when the capital was moved from Rome to Constantinople. Five hundred years go, Lorenzo Valla proved that the document was a forgery; its author spoke of too many things belonging to a period subsequent to that in which his document was supposed to have been written.

When Mary Queen of Scots fled to England in 1568 and there besought the help of her cousin Elizabeth, the Casket Letters were produced in evidence of her wicked character and unfitness for the help she asked. They were claimed to have been written by Mary and to prove her infatuation with Bothwell and complicity in her husband's murder. If really hers, they accomplish this purpose. If forged, they demonstrate the ability of her enemies, being "perhaps worthy to be regarded as the most daring, ingenious, complicated, and skilfully performed forgery on record." The controversy over these letters - always suspected by some of being forgeries, always believed by some to be genuine, but never proved to be either - presents all the questions that appraisal of evidence must take into account: handwriting, style, correctness of allusions, significant omissions, blunders, parallels, period of composition, contemporary examination, disappearance of the originals, etc. But it is doubtful if these questions have ever been considered with perfect objectivity, or can be, unless by some eccentric with no convictions about politics and religion and with no susceptibilities to erring beauty in distress. Mary Stuart's personality is always there, forfeiting one's sympathy or winning it, and leaving one's judgment of the evidence dependent on what one thinks of her already rather than the other way around.

There is a classic example of intensive enquiry in the efforts of Prof. Frank Maloy Anderson, emeritus, of the Dartmouth history department, to determine the identity of "A Public Man" whose purported diary belonged to the critical period of Lincoln's accession to the Presidency. Authorship was anonymous. The task was to learn which of all the public men of the time was the author. All the evidence was in the printed document itself, there being no letters, no manuscripts, no forgeries in which to hunt for clews. But the document indicated that the author was a tall man, interested in business enterprise and politics, widely acquainted in both Washington and New York, an experienced writer, and conversant with French. He had been in New York and in Washington on certain days between 28 December iB6O and 15 March 1861. Off and on over fifty-one years between his first attempts to identify the diarist and the publication in 1948 of his "historical detective story," while all the time busy with teaching and writing, Professor Anderson searched evidence, including - incredibly - the registrations at New York hotels on 20 February 1861. He found his man and incidentally concluded that the "diary" was largely fiction, and very skilful fiction; for there were no blunders such as usually let the cat out of the bag. But judgments were expressed that belonged to a later period and there were statements of fact recognizably embroidered. It is unlikely that any more informative account exists of tenacious, resourceful, and learned scrutiny of evidence than Professor Anderson's.

But to return to Mr. Weems, how do the historians know that he is not telling the truth about the cherry tree? His story is consistent with what is factual in our conception of Washington, whose reputation for probity has withstood pretty well the efforts of the debunker-historians, by emphasis on trivialities, to make him "human." And besides, Mr. Weems was a clergyman. Why doubt his word? To be sure he was an Episcopalian, but Episcopalians were not always judged so harshly as by the contemporary evangelical who explained that is was easier for a codfish to climb a tree, tail foremost, with a loaf of bread in its mouth than for an Episcopalian to get into heaven. No, Mr. Weems was condemned not by rival religionists but by historians and because his standards of historicity were low. The story appeared casually in the fifth edition of his Life of Washington, 1806, along with several other novelties, obviously false, in the same breezy, moralistic, bubbling style. It makes the father exclaim that his son's heroism was "worth more than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver and their fruits of purest gold" - language that is suspect because the elder Washington is not understood to have been given to Ciceronian cadences in his prose, with the feminine caesura so oddly placed. Nor does it describe any known variety of cherry cultivated in the 18th century. Mr. Weems had a bias for morals against facts.

"Liar" is a harsh word, excellent for its purpose. And should it be thrown away on persons who love to tell stories or on the unfortunates who tell the truth as nearly as they can but have no witnesses to uphold their reports? Mr. Weems made no serious effort to deceive. And after all there are many kinds of representation besides the literal. But they should not be mixed-up or substituted for one another. That is dangerous business. Though factual and imaginative writings are both legitimate, the distinction between them should be firm. History must stay close to verifiable facts, and where it can be but conjectural the imperfection must be admitted. Indeed, the cant of readers who profess that the mere sight of a footnote annoys them is far worse than the cant of those who complain of so much as a breath of invention, because there is more call for accuracy and seriousness in this world than for impressionism and frivolity. But at least until the abominable new missiles begin to fly, there remains room in our culture for both footnotes and fancy - and not room alone but need.

Bray Hammond, the author, lives in Thetford, Vermont, and is engaged in research at Baker Library, where he is a daily visitor. The Pulitzer Prize in history was awarded him in 1958 for "Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Feature

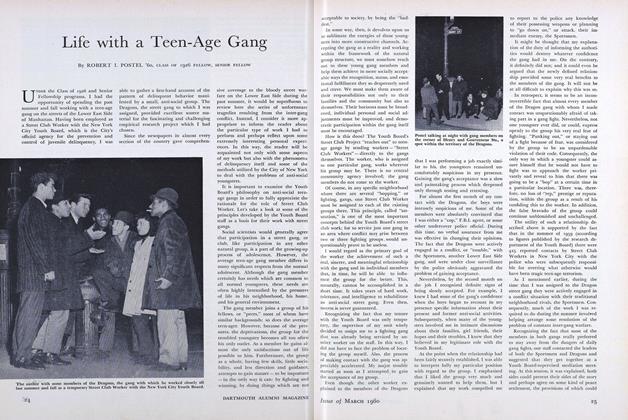

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH