A YEAR or so ago Life published an account with photographs of some Ledyard Canoe Club members on the annual trip from Hanover to Saybrook. The pictures were interesting to me since I made the particular voyage four times in the somewhat distant past. A remark attributed to a dean that few men ever undertook the trek more than once because of its arduous nature stirred some standard reflections about the old days and the decreasing vitality in general of contemporary undergraduates.

I had some of the ambivalent feelings most people do about such a story as it is done in Life. It seemed reasonable to permit humanity to get a close-up of one of the rituals which are part of the Dartmouth Myth. At the same time it seemed regrettable that another of the hitherto uninvaded areas of idyllic charm had been violated by Luce employees, their reports always conveying the impression, in such cases, of an enterprise undertaken by eccentrics and bordering on the buffoonish. The prose as well as the pictures expressed faithfully the condescending amusement Life seems to feel at every additional demonstration of what it considers human folly.

Not knowing whether the photographer followed the hegira by helicopter or got his pictures from a motorboat, I wondered if members of the Canoe Club might have been so bemused by the prospects of a spread in the famous magazine that they paddled a Life man and his cameras all the way from Hanover to Saybrook. It finally occurred to me that the most likely explanation was that some wily member of the Club sold the idea to the magazine and took the pictures himself.

It was in 1935, at the end of my sophomore year that I first decided to take the trip about which I'd heard so much. Dan Quilty '38, who like myself lived in Bridgeport at the time, let himself be sold on the idea. Dan had done little if any paddling previously. We paddled several miles every day for a couple of weeks to get him ready. He became an excellent bowman in short order, though it was only the combination of youth and naive enthusiasm which led him to venture to paddle five days from sun-up to sun-down with so little preparation.

It's now slightly more than a quarter of a century since we shoved off on a warm June morning. This is a length of time sufficient to invest almost any happening, however trivial, with respectability and interest, and so it is in this instance, at least in my own mind.

The trip was a lot of fun and uneventful. It took the usual five days of steady paddling. The weather was good, as it was on each of the subsequent trips. I had a memorable tan, whereas Dan who hadn't taken off his clothes or his hat the whole way lest he get his fair skin burned to a crisp was outwardly un- changed except for a scraggly growth of beard. We left the canoe tagged for shipment back to Hanover in the backyard of a friendly Saybrook family. They always were most cordial about giving us a hand at the end of our trips, though I find I can't recall their name.

The following year Ralph Ruggles '36 paddled bow with me. Art Ekirch and Jim Luttrell, both '37, accompanied us in a second canoe. It was the first of three trips for Art. He went on to become a professor of history. At that time he was gifted with remarkable strength and endurance even though his major interest lay in the realm of scholarly endeavor.

Approaching the first portage at Wilder Dam, Jim who was paddling stern let his canoe come uncomfortably close to the place where the river rushed into the cavernous depths of the power plant. Ralph remarked with his typical humor that he trusted Jim would be careful because he doubted either Jim or Art would be very good men in a turbine. Jim was wary enough, however, and went on to heroic achievements as a bomber pilot during the war.

One night we camped on the edge of a tobacco field. Ralph put his sleeping bag down on some smooth, recently ploughed ground, arranged his mosquito netting on sticks and crawling under, went to sleep. A little later he began to cry out in alarm. When we went over to him he complained groggily that it felt like insects were crawling all over him and dropping on his face. It seemed unlikely in view of the netting, but when I turned a light on him we saw that the underside of the netting was almost black with countless ants. He had apparently bedded down on a nest of them, and it was a while after he had moved to another location before he was composed enough to get back to sleep.

At Saybrook Ralph got out at the long bridge across the river. The road to Hanover ran across it then. We'd figured that if he started hitch-hiking back as soon as we got to the bridge he would get back in time for his graduating ceremonies. It was his senior year. We had been good friends, and had paddled around on the river, swimming and sunbathing all spring. It was with a particular feeling of bereavement and a keen awareness of the nature of life with its meetings and farewells that I took up my paddle to go on. He stood on the bridge waving and calling down the ribald commentaries which seem appropriate at such times. The drama of the moment struck me and I called out, "Just think, Ralph, this is probably the last time I'll ever see you." This turned out to be correct, and though I have heard he lives and works in Cleveland, I haven't so far encountered him again.

The third trip was just before my own graduation. Art Ekirch was my bowman. Bill Timbers and Paul Dickson, both '37, took the second canoe. Bill had to be back in four days for a ceremony in which he was to participate. We'd never made the trip in less than five days but thought by dint of extra effort it might be possible to do it in four so Bill could come with us.

Being a member of the Canoe Club, Bill was used to paddling. Paul hadn't done much of it, though he was then as he is now an imposing specimen. He weighed around two hundred pounds and was about the tallest man in the class. He was an all-round athlete, though he didn't make a profession out of it during the college years.

Paul, who went to Tuck School and into business, was never inclined to loll around in the sun behind the dorms or out on the sandbanks as the majority did in those days. He felt it was a waste of time and preferred some kind of purposeful endeavor. As a result he didn't have much tan.

We started off in good spirits on a bright sunny morning. The fact that Paul outweighed Bill, his bowman, by fifty or sixty pounds created a situation where Bill rode high out of the water with Paul almost awash in the stern. Nobody had the presence of mind to put a few rocks in the bow and so Bill had to reach down quite a way to get his paddle properly into the water. This was too tiring to keep up for long. As a result Paul had to put forth extra effort with each stroke to keep up with Art and myself who weighed about the same.

It was the custom on the trips then, as it may still be, to go most of the time with nothing on. The banks were largely devoid of civilization and there were few motorboats around. Paul, even though mostly untanned, stripped down like the rest of us.

By night he was painfully sunburned all over except for the areas unexposed due to the conventional sitting position. In addition the unaccustomed activity of paddling made him a mass of stiff and painful muscles. Despite these acute discomforts he remained a cheerful and untiring companion throughout.

As if all this were not enough, the first morning just below Hartland Falls, Paul and Bill got too close to a large rock around which was a marked eddy. I happened to glance back at that moment and saw them at a forty-five-degree angle as they were turning over. Art and I found our amusement tempered by the concern about getting them ashore and rescuing clothes and blankets. The thing which most forcibly struck us all at this juncture was the sight of a dozen oranges which were loose and floating around.

"Get the oranges!" someone shouted, and for several minutes we were all busy rounding them up and getting them in our canoe. When they had been retrieved we picked up the packs which were still afloat and dragged the canoe ashore. The most serious loss was a pair of trousers containing Paul's wallet and money. Outside the dilemma produced by this mishap the main concern was to get everything dried out. Since the sun was hot the blankets and clothes spread out in both canoes like itinerant laundry were quite dry by night.

Because of headwinds and the distance involved we made it only to Middletown by the end of the fourth day, some thirty miles from Saybrook. We'd paddled till midnight once or twice but it didn't suffice. Bill had to leave us. After graduation he began the distinguished legal career which led to his becoming a federal judge. He was one of Governor Thomas Dewey's bright young men when Dewey was in the ascendent and Life had not yet elected him president. I later saw Bill occasionally around New Haven where we were both graduate students, and once on a glacier in Estes Park, but I remember him best perched high in the bow of his canoe, paddling comfortably while emitting raucous crow calls, the verisimilitude of which seemed to be doing little to ease the look of tortured concentration we could see on Paul's face as he worked doggedly along.

The fourth and final trip was in 1938 when my brother was ending his first year at Dartmouth. He persuaded a classmate, Bob Floughton, to paddle bow for him. Art and I were making our last trip. The fact that between us we were about to bring our total times down the river to seven would have been even more satisfying to us than it was had we known what the dean was going to say twenty years later.

On the last trip things went pleasantly with little that stands out in my memory. Above Hartford where we were bedding down for the night in a pile of hay in an open shed, Bob decided he wanted to spend the last night of the journey in a bed. He went across the river and located a tourist cabin. It was the best he could find since motels were yet to be invented. It was not in keeping with the Ledyard mystique but perhaps at this late date no harm will be done by mentioning it.

My brother James, or Jim as he was called at college, had a great talent for imitating all sorts of voices. It was part of the reason for his success as a member of The Players. One of the things I recall vividly from this trip was his frequent renditions of one of the most fa- mous voices of the time, F.D.R.'s. I haven't followed Bob's career since, as it has been difficult enough to keep up with my own, not to mention that of some five hundred classmates. James continued with his interest in the theatre and at present has a couple of plays he wrote optioned for production in New York.

I have canoed some since the Hanover days, especially in the last three years during which I have owned an aluminum canoe. Until moving recently to Wisconsin, which is reported to have nine thousand lakes and no doubt as many rivers, I used the canoe on Lake Tillery in North Carolina. The waters in the Piedmont portion of the state are inclined to be muddy, and the summers are very hot. I sometimes thought as I paddled around on the yellow-tinged waters under a blazing July or August sun that it was an odd outcome, in a way, for someone who had paddled a few thousand miles on the crystal lakes and rivers of New England, and who at one time was the official authority for the Canoe Club and the State of New Hampshire on the Connecticut River from Hanover to Saybrook.

At times I wonder if the real purists would own or even get in a metal canoe. I imagine there must be groups somewhere who are certain God never in- tended canoes to be made out of anything but wood and canvas. It may be shameful to admit it, or perhaps it's an indication of the failing faculties of advanced years, but I like metal canoes. I can run into a rock or see my nine-year-old son Reid drop his end with a crash, as he did once on a portage when he tripped, and it doesn't matter. No doubt Spengler or Toynbee would correctly diagnose such an attitude as a sure sign of the imminent collapse of our civilization, but it is hard to struggle against the tides of history.

Canoe trips down the Connecticut do have an impressive irrelevance when compared with what other and hardier Dartmouth men have done exploring Antarctica or ascending the remaining Everests of the world. But for those more moderately endowed with the spirit of adventure the River can serve in a pleasant and memorable way as Everyman's Amazon, Matterhorn and Northwest Passage combined in a neat five-day package.

I imagine the trip isn't quite the same at it was twenty-five years ago, but neither am I. Canoeing, though, is just as much fun as it ever was, and I find myself thinking now and then a bit wistfully that I'd like to locate one of my old bowmen and see if we could still make it to Saybrook in five, maybe ten, days.

Even if we didn't go until 1963 it would still be a celebration of the silver anniversary of one of the trips. I suppose there are Dartmouth men who have paddled down the river more than four times but I never happened to know or hear about them. I accept the notion that there have been eccentrics who have done it ten or twenty times. There are always people like that around Hanover.

The last I heard, a few years back, the speed record set by Butterworth and Moseley from the College to Saybrook had never been broken. They were both in my class and they set the record during their undergraduate years. It's one I don't expect to challenge, and probably they won't either.

DR. ANDREWS, a physician in Wausau, Wisconsin, was the author of "The Return of the Log-Peeler" in our January 1961 issue. At that time we promised this second reminiscent article about his outdoor life at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

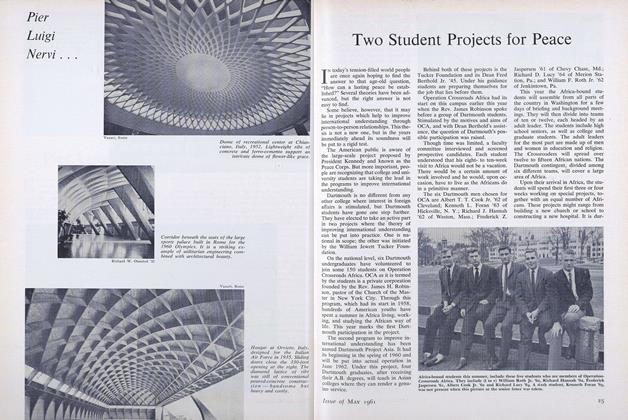

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

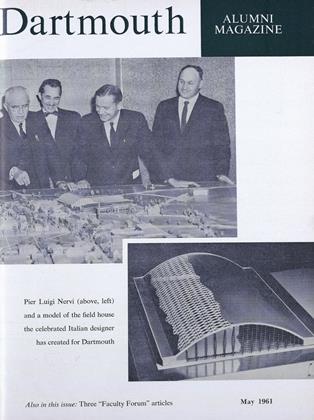

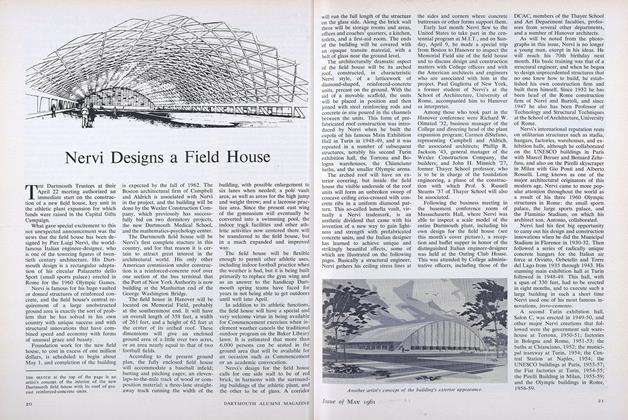

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961

GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37

Article

-

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Club

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleCollege Receives Bequests

February 1945 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

April 1962 -

Article

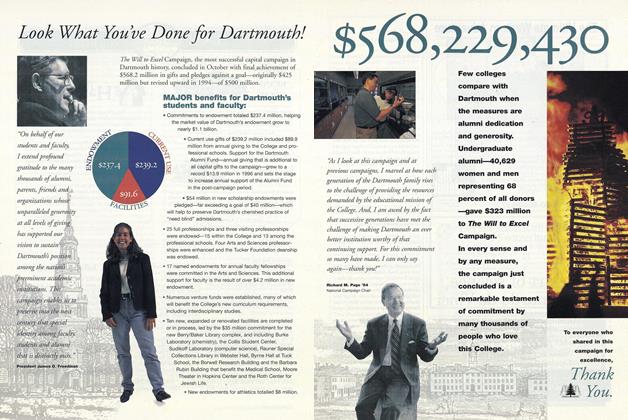

ArticleLook What You've Done for Dartmouth!

JANUARY 1997 -

Article

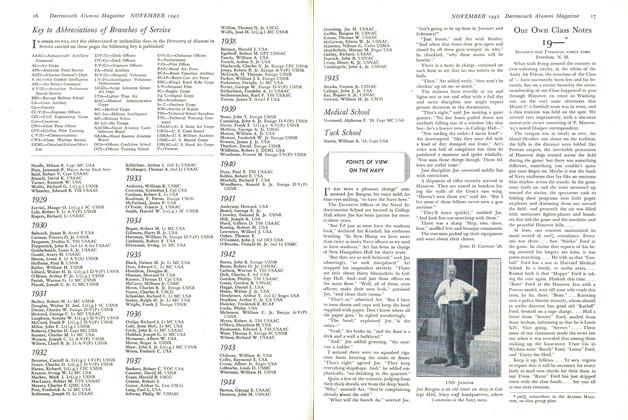

ArticlePOINTS OF VIEW ON THE NAVY

November 1942 By Jonh D. Cannon '26 -

Article

ArticleWhen We Were Freshmen

May 1935 By Warde Wilkins '13