THERE is one point in particular, not discussed by the seniors, which has become of some concern to me. Speaking somewhat metaphorically, I would like Dartmouth to be more than a trade school for snobs. The College should return education, particularly in the humanities, to the students.

The student today is bounded with pressures for higher learning. Society demands it of him, his parents demand it of him, and he demands it of himself. Graduate schools, fellowship committees and professional schools, not to mention future employers, continually look over his shoulder as he studies. The College elaborates upon these pressures with quizzes, hour exams, papers, class reports, theses, final exams, comprehensives, independent reading lists for underclassmen, majors and some particular courses, plus exams and papers on the independent reading, and finally Great Issues journals. These pressures have most recently been focused by the three-three system.

Such artificial strictures emphasize the mechanical side of learning, and tend to produce insensitive machines rather than men. If it is true that "you've got to be a machine to be successful," then it is education for the status quo, a dubious reality. One of the most important goals of education is the development of a double consciousness. The first has to do with substantive or prescribed material, and is a commitment, an immersion in the process of learning. The second, having to do with the self, is an awareness of the nature of this commitment. Mechanized learning impedes the development of the second aspect of this double consciousness. Further, mechanization removes the student from the avant garde, by stressing knowledge only of what can be proven, a triumph for the repressive side of the scientific attitude. I am not arguing for an undisciplined mind. I am not advocating an education in unreality. What I do desire is more freedom in learning, an education uncluttered by self-conscious and repressive gauges of achievement.

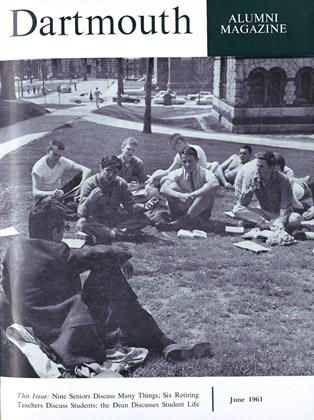

Dartmouth is famous for its school spirit. It possesses a kind of spontaneity which has filled the chests of proud alumni, and the coffers of the College. It is the spontaneity which creates an inspired riot. Unfortunately, Dartmouth is too lacking in spontaneity in the classroom. The mechanics of education have put learning purely on the terms of a job to be done. One need only walk along fraternity row on a big weekend to grasp the feverishness with which the student attempts to escape from the onerous detail of learning.

The politeness of the academic tradition in a small, cloistered, self-satisfied community such as Dartmouth quite literally asphyxiates the excitement of learning. There is a messianic conception now floating around that the industrial revolution which has finally reached Dartmouth with the construction of the Cold Regions Engineering Laboratory, the new dorms, field house, math-psych building, and Hopkins Center will, besides providing a shelter for learning during the cold winters up here, encourage all the needed spontaneity and creativity. Many doubt it.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

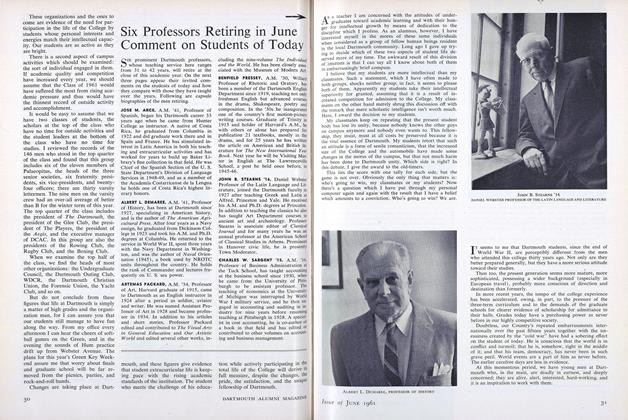

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

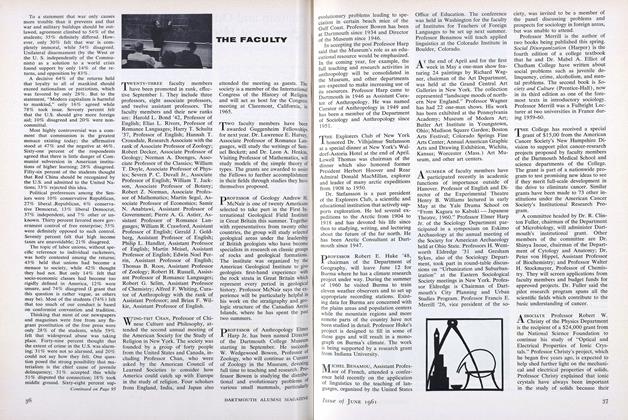

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42

TOM DALGLISH '61

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1960 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

January 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61