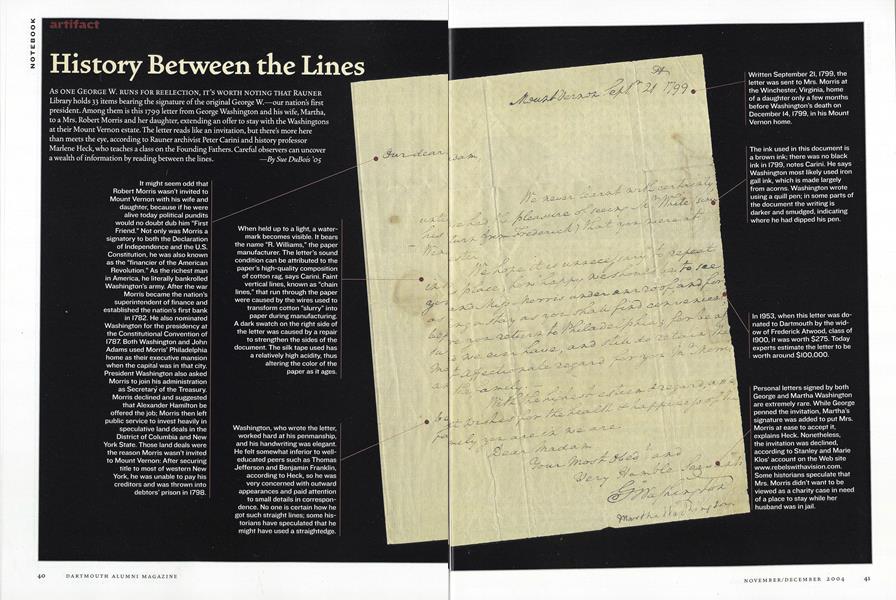

As ONE GEORGE W. RUNS FOR REELECTION, IT'S WORTH NOTING THAT RAUNER Library holds 33 items bearing the signature of the original George W.—our nations first president. Among them is this 1799 letter from George Washington and his wife, Martha, to a Mrs. Robert Morris and her daughter, extending an offer to stay with the Washingtons at their Mount Vernon estate. The letter reads like an invitation, but there's more here than meets the eye, according to Rauner archivist Peter Carini and history professor Marlene Heck, who teaches a class on the Founding Fathers. Careful observers can uncover a wealth of information by reading between the lines.

It might seem odd that Robert Morris wasn't invited to Mount Vernon with his wife and daughter, because if he were alive today political pundits would no doubt dub him "First Friend." Not only was Morris a signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, he was also known as the "financier of the American Revolution." As the richest man in America, he literally bankrolled Washington's army. After the war Morris became the nation's superintendent of finance and established the nation's first bank in 1782. He also nominated Washington for the presidency at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Both Washington and John Adams used Morris' Philadelphia home as their executive mansion when the capital was in that city. President Washington also asked Morris to join his administration as Secretary of the Treasury. Morris declined and suggested that Alexander Hamilton be offered the job; Morris then left public service to invest heavily in speculative land deals in the District of Columbia and New York State. Those land deals were the reason Morris wasn't invited to Mount Vernon: After securing title to most of western New York, he was unable to pay his creditors and was thrown into debtors' prison in 1798.

When held up to a light, a watermark becomes visible. It bears the name "R. Williams," the paper manufacturer. The letter's sound condition can be attributed to the paper's high-quality composition of cotton rag, says Carini. Faint vertical lines, known as "chain lines," that run through the paper were caused by the wires used to transform cotton "slurry" into paper during manufacturing. A dark swatch on the right side of the letter was caused by a repair to strengthen the sides of the document. The silk tape used has a relatively high acidity, thus altering the color of the paper as it ages.

Washington, who wrote the letter, worked hard at his penmanship, and his handwriting was elegant. He felt somewhat inferior to well- educated peers such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, according to Heck, so he was very concerned with outward appearances and paid attention to small details in correspondence. No one is certain how he got such straight lines; some historians have speculated that he might have used a straightedge.

Written September 21, 1799, the letter was sent to Mrs. Morris at the Winchester, Virginia, home of a daughter only a few months before Washington's death on December 14, 1799, in his Mount Vernon home.

The ink used in this document is a brown ink; there was no black ink in 1799, notes Carini. He says Washington most likely used iron gall ink, which is made largely from acorns. Washington wrote using a quill pen; in some parts of the document the writing is darker and smudged, indicating where he had dipped his pen.

In 1953, when this letter was donated to Dartmouth by the widow of Frederick Atwood, class of 1900, it was worth $275. Today experts estimate the letter to be worth around $100,000.

Personal letters signed by both George and Martha Washington are extremely rare. While George penned the invitation, Martha's signature was added to put Mrs. Morris at ease to accept it, explains Heck. Nonetheless, the invitation was declined, according to Stanley and Marie Klos' account on the Web site www.rebelswithavision.com Some historians speculate that Mrs. Morris didn't want to be viewed as a charity case in need of a place to stay while her husband was in jail.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

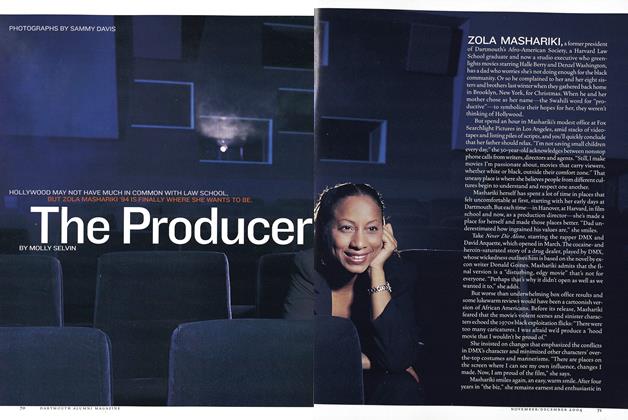

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Sports

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83

Sue DuBois '05

-

Article

ArticleThe 10 Most Coveted Jobs On Campus

May/June 2004 By Sue DuBois '05 -

Article

ArticleActing Locally

Sept/Oct 2004 By Sue DuBois '05 -

Article

ArticleClass Of 1989

Nov/Dec 2004 By Sue DuBois '05 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1965

Mar/Apr 2005 By Sue DuBois '05 -

Article

ArticleLEEDing the Way

July/August 2005 By Sue DuBois '05 -

Article

ArticleClass of 2004

July/August 2005 By Sue DuBois '05