FORMER WASHINGTON BUREAU CHIEF, UNITED PRESS INTERNATIONAL

On April 1, 1940, I saw the flood-lighted magnificence of the Capitol dome for the first time as a newcomer to Washington. On October 2, 1961, as the Detroit-bound plane climbed into the western sky, I saw the sunsetgilded dome for the last time as a newspaperman.

Between this hail and farewell to a Washington newspaper career were years crowded with incredible events; years of convulsive turmoil - political, social, economic; years of enormous change, of breath-taking scientific and technological advances.

This was an era of tragedy and triumph, of dark despair and bright promise. Brave men fought and died in the bloodiest war of all time. Giants strode across the world stage. So did some small men who, in trying to wear the garments of greatness, only in looking like tyrannical Charlie Chaplins. Some of the giants passed away. So, fortunately, did some of the tyrants.

This was the era when a single great explosion and a blinding flash in the desert at Alamogordo, N. M., thundered the dawn of the atomic age - a terrifying thing or a blessing, whatever mankind chooses to make of it. This, too, was the era that spawned the jet and space ages; that saw the United States emerge from its posture as a slumbering, reluctant giant and become the most dominant power on earth. It was an era when medicine made dramatic breakthroughs in developing life-saving antibiotics and vaccines, when the dread scourge of polio finally was subjugated. New nations and two new states — Alaska and Hawaii - were born. Some old concepts died.

For nearly 22 years it was my rare privilege - and awesome responsibility - to help report many of these momentous events to the world. Most times, a reporter-editor's chair in the Washington Bureau of United Press International served as a press-box seat to witness great moments of history in the making.

Many times, however, an unconquerable restlessness, an irresistible desire to be where the big news was breaking, an irrepressible urge for adventure - whatever it was (and it was perhaps a combination of all these) - lured me away from Washington. There were journeys across the length and breadth of the land and to faraway places - to battlefields on Kwajalein, New Guinea, the Philippines, Iwo Jima; to Australia and New Zealand; to the Arctic Circle, Europe, North Africa; to a famed "Kitchen" in Moscow and to the forbidding vastness of Siberia; to elegant palaces where potentates lived and to miserable desert shacks that sorely tested the morale of their GI tenants. Sometimes you traveled plush, sometimes steerage; maybe a jet or an ox cart, a presidential campaign train or a troop train.

Wherever you went, you met people who acted like reporters - they asked questions, too. How do you go about keeping the public informed on what goes on in Washington? What is it like being in the news hot spot of the world? What kind of people are the leaders of government? How well did Nixon stand up against Khrushchev? What President did most with a press conference? What were some of your experiences? What effect has television had on covering the news? Has the job of gathering and presenting the news changed much?

WHAT was it like? It was like this: My first major assignment in Washington was to attend a President Roosevelt press conference. My last was a President Kennedy press conference.

These two events bridged the years. They dramatized the march of history, the tremendous changes we have witnessed in Washington since 1940 — in the techniques, the technicalities, the amazing growth of reportage in the Capital. In their contrasts, they reflected the shifting emphasis of the news, the gigantic strides made by science, the take-over of the new generations, the emergence of Washington as the undisputed news center of the world. For, the presidential press conference is the fountainhead of news in Washington.

Presidential press conferences - as the regular, spontaneous news-makers we know them to be today - were brought to Washington by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the master newsmaker of our time. He. perhaps more than any other chief executive before or since, realized their vast potential and extracted the ultimate from them. In his day, reporters - normally about 100 or more - crowded around his desk for his twice-a-week sessions. They stood. FDR sat, his head tilted back, his cigarette holder angling jauntily from the right corner of his mouth. There was an atmosphere of bantering, person-to-person informality until the guards signaled "All in!" and closed the doors. Then the jousting started. Questions and answers bounced back and forth. (You could not quote the President directly.) Perhaps a question would come from a reporter the President did not know. It didn't matter. (In those days, reporters were not required to stand on the formality of identifying themselves and their news media affiliation before asking a question.) The freeswinging, catch-as-catch-can, question and answer was the thing. FDR relished this man-to-man, head-to-head combat.

At that first-for-me FDR press conference the questions dealt mostly with domestic matters, especially Mr. Roosevelt's views on a then more-or-less politically obscure utilities lawyer named Wendell L. Willkie.

Late last summer, when I sat in on my last presidential press conference, I could not help reflecting upon the changes that had been wrought since that first one. Now, the conference — by a process of evolution from one administration to the next - had become a major theatrical and electronics production.

At a given moment, the President of the United States entered the plush new State Department auditorium through a door on the right. He strode briskly to a microphone-studded lectern on a slightly elevated, floodlighted stage. Still, movie, and TV cameras went into action. Mr. Kennedy faced an audience of more than 425 reporters, deep in cushy, theatertype orange leather seats. The President had some announcements, then recognized a reporter for the first question. The glowing little red eyes on the TV cameras fixed their stare on the standing reporter who dutifully and politely went through the necessary formality of identifying himself: "Mr. President ... So-and-so of the Such-and-such Press ... As soon as Mr. Kennedy appeared to be about to finish his answer to the question, dozens of reporters bobbed up seeking recognition by calling: "Mr. President! ... Mr. President!" Mr. Kennedy would point a finger of recognition at one who then would identify himself (even though personally known by the President). Precisely 29 minutes after Mr. Kennedy opened the conference, a "Thank You, Mr. President" from the senior wire service reporter closed it. That day, the questions told the story of the changing emphasis of the news ... Cuba, Laos, Berlin, Soviet and American space achievements. Within minutes after the conference ended, reporters telephoning their stories were supplied transcripts of the conference - for direct quotation of the President's remarks.

EACH of the last four Presidents has contributed substantially to the drastic changes in the format of presidential press conference.

FDR was perhaps the greatest innovator. He made the presidential press conference a going concern. His predecessor, President Hoover, held conferences only rarely, and then to answer written questions that had been submitted in advance. Mr. Roosevelt made them part of the normal operating procedure of the presidency.

President Truman made the first significant change in the format created by Mr. Roosevelt. For about three years, Mr. Truman operated much like his predecessor. Then, irked by needling questions from reporters he either did not know or could not see because of the mob scene in front of his desk, he determined that reporters who ask questions should stand up and be counted. He switched the press conferences to the old State Department Treaty Room and laid down a new set of rules: The President would stand. Reporters would sit. If they wished to ask a question, they must stand and identify themselves and their news media. That's still the rule.

President Eisenhower also added some important new touches. He permitted filming and sound recording of his press conferences for later television and radio use - after he and his press secretary, James C. Hagerty, had gone over the transcript of his remarks. Hagerty also inaugurated the technique of releasing the entire transcript of the President's remarks for direct quotation, after he had cleared it.

President Kennedy put the presidential press conference in the new State Department auditorium - and into American living rooms on live TV. His very first one was televised live. This created a host of new coverage problems for the wire services. No one may leave a press conference room until the conference ends. Before live TV, that worked well because everybody started from scratch after the conference. But, with live TV bringing the President's words to the world the minute he uttered them, and with reporters still not permitted to leave the auditorium until the conference ended, the pad and pencil reporters faced an enormous competitive disadvantage.

Accordingly, the wire services were compelled to revise their press conference procedures and devise additional types of reporting in order to get stories on the wires while the conference was in progress. This, however, applied only to live televised press conferences. Only seven of Mr. Kennedy's first 29 went on live TV.

Veteran Washington reporters generally agree that FDR used press conferences most effectively and exercised the best control over them. Because of the relative smallness of the group, it was possible at Roosevelt press conferences to explore a subject more thoroughly and thus acquire a better understanding of it. Sometimes this was at the risk of incurring FDR's impatience. In that case, he might say: "Oh, for God's sake, haven't we exhausted that subject? Let's get on with something else."

Mr. Kennedy does not possess FDR's dramatic sense of timing - yet. That may come later. But he is gifted with more natural newspaper savvy than any of his three immediate predecessors. And he has a masterful public relations approach. Once a newspaperman himself, he probably knows and calls more reporters by their first name than any other President.

PRESIDENT KENNEDY has used the relatively tively new medium of television skillfully and adroitly. His live televised press conferences, for example, give him an opportunity to carry his case for certain legislation directly to the people. This, in many ways, is far more effective than sending a special plea to Congress. It also makes it unnecessary, except in most urgent situations, for him to prepare and deliver a separate TV address. Mr. Kennedy has made comparatively few major TV speeches.

Television has brought new and (in many ways) healthy challenges to the task of reporting the news from Washington, and elsewhere.

It has made the skilled craftsman - the old pro — an even more discerning and accurate reporter. (His professional pride wouldn't let him be caught dead making an error of description on something a televiewer had seen on his screen.)

It has alerted editors to the need for a new dimension in reporting - for more background stories, more interpretive stories, more stories which take the reader behind the scenes where the TV camera cannot penetrate.

It has helped increase the output of news from Washington, particularly the type of news that is developed from panel discussions.

It has advanced the politician's access to the public. (This may be a mixed blessing and not necessarily productive of real information to the public since a number of politicians, when exposed to a TV camera, give off more heat and histrionics than light.)

It has sharpened the public's awareness of presidential press conferences and of what goes on at national political conventions.

It has made, and destroyed, presidential candidates and lesser figures.

Along with Washington's emergence as the world's No. 1 news center, it has swelled the army of Washington correspondents - the people who dedicate themselves to the monumental task of keeping the nation and the world informed about what goes on in the Capital.

In 1940 there were 527 accredited newsmen and only 39 accredited radio correspondents in Washington. Today, there are 845 accredited newsmen and 253 accredited TV and radio correspondents. It takes all this manpower to report the news, for not only is there a great flow of news, it is far more complex and requires more specialists. And news is sometimes hard to get at.

Whatever administration is in power, there is always a full-time job of mining the news. Human nature being what it is, no administration likes to have unfavorable stories reach the public. To this extent, there may be - and sometimes is - an effort by some individual in government to suppress information. Sometimes this is done in the name of national security, sometimes for the more nebulous reason of "national interest." In my 22 years in Washington, no reporter worth his salt ever - to my knowledge - put a news beat ahead of genuine national security.

On the other hand, no reporter worth his salt ever would allow himself to be deflected from his objective of digging out news the American public has a right to know.

No honest-to-goodness Washington reporter ever settles for what is put out in a government press agent's release. My favorite guy is what I choose to call a pick-and-shovel reporter - the one who digs for his news, the one who looks for the "why" and "how," not just the "who, where, when, and what."

I THOUGHT about this wonderful breed of guy some nights ago when my plane skimmed in over Washington. That lovely city's lights blazed like a hundred thousand jewels in a royal crown. And the biggest, brightest jewel in the crown was the flood-lighted Capitol dome. The spectacle tapped a flood of treasured memories of experiences - some tragic, some exhilarating - that came to me because I was lucky enough to be a reporter:

That first Roosevelt press conference . . . Writing stories about the gathering crisis in World War II - the Roosevelt-Churchill Atlantic Charter conference, the draft, the sinking of American ships by U-boats, the Japanese "peace" envoys in Washington, the grim warning by a Japanese correspondent who told you the Friday night before Pearl Harbor, after talking to Tokyo, that "things look bad" ... Pearl Harbor Sunday ... The U.S. declaration of war against Japan ... The surrender of the gallant garrison on Wake Island ... and on Corregidor ... Defeat ... Defeat... Then the turning point with the great victory at Midway ... The great "lift" from the Doolittle raid on Tokyo ... Mac Arthur's flight to Australia and his pledge to return ... The great naval battles of the Pacific ... The Roosevelt-Churchill conferences ... D-Day ... Covering FDR's last campaign ... The tour of duty as war correspondent in the Pacific ... FDR's death ... VE Day ... The A-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ... Peace! ... Political conventions ... Truman's 1948 upset victory ... The attempted assassination of Truman in 1950 ... His firing of Mac Arthur ... Eisenhower's election ... The shooting in the U.S. House of Representatives ... The Supreme Court's desegregation decision ... McCarthy ... The Eisenhower heart attack ... Sputnik ... Explorer ... Man in space.

These and many other stories I wrote, covered, or handled as an editor.

After a career has ended, you take inventory and ask yourself: "What experience stands out most vividly?" You get lots of answers. But if you ask yourself what was the most fantastic journalistic adventure, you have to vote for the trip to Russia and Poland with Vice President Nixon in 1959.

What was it like covering that trip? Exhausting. Stimulating. Frustrating. Challenging. Aggravating. Exhilarating. And - fantastic!

Within 24 hours after arriving in Moscow on a non-stop flight from New York you found yourself face-to-face with Khrushchev in his Kremlin office. Like a Sovietized Li'l Abner showing off, he bounced a stainless steel ball in his hands to let you know that this was a replica of the sphere the Russians had planted on the Moon. Then, when Nixon arrived at the Kremlin, Khrushchev got right down to business and - you learned later - cut loose with a barrage of one-syllable barnyard language. But this was only the beginning.

Soon afterwards, Mr. K engaged Nixon in a preliminary skirmish in a TV studio at the U.S. exposition. He tried to badger and humiliate the Vice President with loud talk and ridiculing gestures. Khrushchev appeared to have won that one on points, but when they came to the main event in the "Kitchen," it was another story. By now, Nixon was quite aware of his adversary's tactics. He was ready for him, too. The debate that ensued was incredible. It was, as one bystander said, like two people tossing the H-bomb back and forth at each other while you stood there in breathless fear wondering who'd drop it. Nobody dropped it. But Khrushchev knew, and those who heard him knew, that Nixon had won this one. (And you told the Vice President he'd done a good job.)

Trying to take notes on the debate was a true test of stamina. Crowds surged in against you, stepping on feet - Nixon's, Khrushchev's, everybody's. They pushed, shoved, elbowed. Somebody shoved you. You shoved back and discovered you'd also elbowed the President of the Soviet Union - Voroshilov.

This was the way it was all the way - battling crowds, jockeying for position with Russian reporters and hecklers, bucking the line trying to get by security guards. You had to stay close to Nixon or risk missing the big story because he made news everywhere he went. It could be at the top of a dam in central Siberia, 700 feet underground in a copper mine in the Urals, or in front of a model kitchen. Only once did you encounter Khrushchev in something less than a mob scene. That was at his dacha. By the toss of a coin, you'd won the privilege of being the American pool reporter for a Nixon-Khrushchev meeting at Mr. K's country estate. As the two men walked along together, you joined them and took notes of their conversation. It was then that the Russian premier and the American reporter had a small summit meeting on the question of the volume and accuracy of the reporter's notes.

From beginning to end, it was all like a strange dream.

These were some of the memories.

There were other memories - of many top people you'd met or interviewed. With rare exceptions, all fit that simple prescription for greatness: "The bigger they are the nicer they are."

There were memories of a passing parade of great statesmen, great reporters - and a special thought about a great profession.

Finally, you recalled again the thrill of that moment when you'd seen the Capitol dome for the first time. You had come to Washington then with a set of ideals that had been instilled in you as a boy.

Now, all these years later, you felt a special kind of warmth inside. Those ideals were still intact.

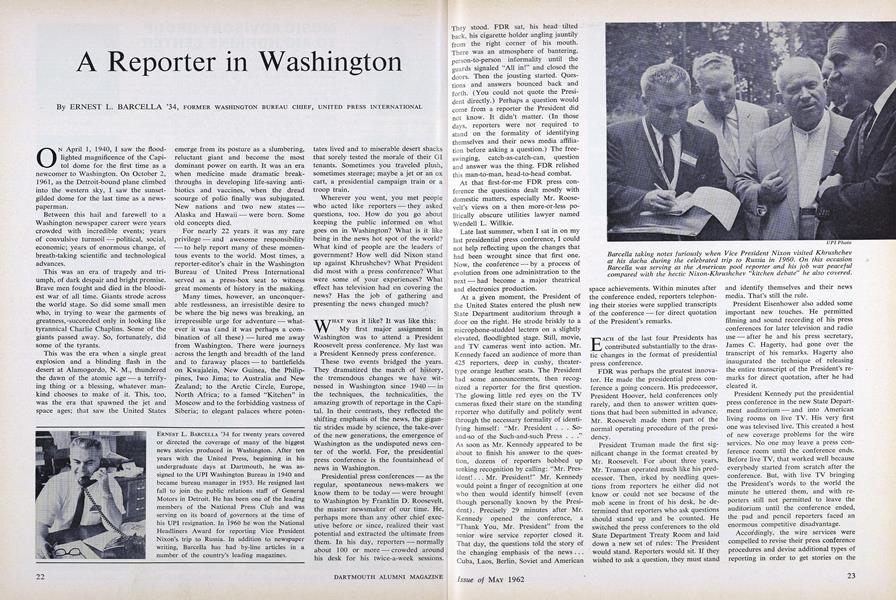

Barcella taking notes furiously when Vice President Nixon visited Khrushchevat his dacha during the celebrated trip to Russia in 1960. On this occasionBarcella was serving as the American pool reporter and his job was peacefulcompared with the hectic Nixon-Khrushchev "kitchen debate" he also covered.

President Kennedy gets his National Press Club membership in 1961 as club presidentJohn Cosgrove, former club president John O'Brien, and Barcella (right), member ofthe board of governors, do the honors on behalf of the Washington press corps.

Barcella, sharing seating honors with President Truman (and more nattily dressed),at an informal presidential press conference in Key West, Florida, in March 1951.

ERNEST L. BARCELLA '34 for twenty years covered or directed the coverage of many of the biggest news stories produced in Washington. After ten years with the United Press, beginning in his undergraduate days at Dartmouth, he was assigned to the UPI Washington Bureau in 1940 and became bureau manager in 1953. He resigned last fall to join the public relations staff of General Motors in Detroit. He has been one of the leading members of the National Press Club and was serving on its board of governors at the time of his UPI resignation. In 1960 he won the National Headliners Award for reporting Vice President Nixon's trip to Russia. In addition to newspaper writing, Barcella has had by-line articles in a number of the country's leading magazines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMON MARKET

May 1962 By WALDO CHAMBERLIN -

Feature

FeatureSGT. BROWN'S RUGGED BOYS

May 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Feature

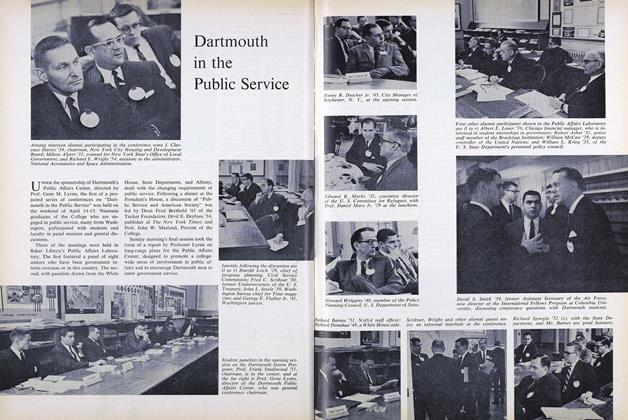

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

May 1962 -

Feature

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1962 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

Features

-

Cover Story

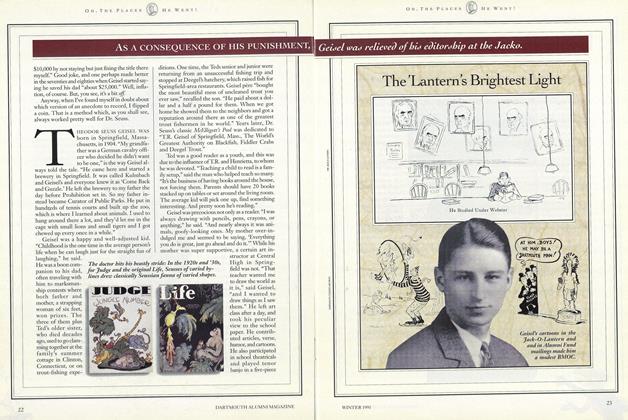

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

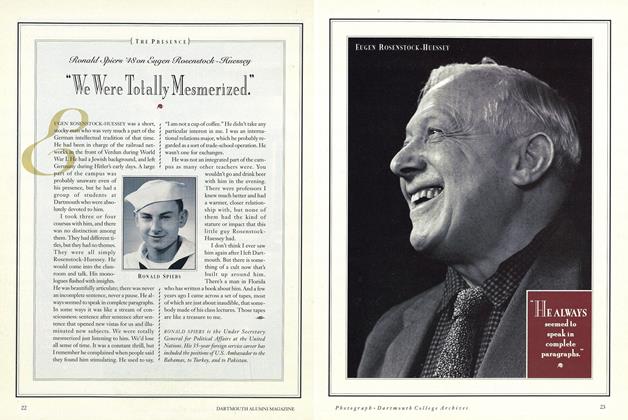

FeatureRonald Spiers '48 on Eugen Rosenstock-Huessey

NOVEMBER 1991 By Eugen Rosenstock-Huessey -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82