The following account of a visit to Mt.Moosilauke was written by William B. Rotch'37 for The Milford (N. H.) Cabinet, ofwhich he is editor. With his permission, andwith the wish that his article had appearedin our magazine in the first place, it is reprinted in full. Mr. Rotch, former Undergraduate Editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, is now a member of our Alumni AdvisoryBoard.

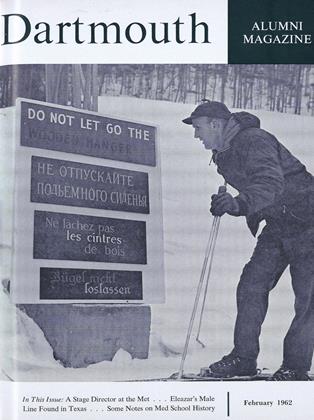

On the slope of Mt. Moosilauke stands the Dartmouth Outing Club's Ravine Lodge, its log walls firm against the winter winds that sweep down from the mountain peaks. Last week-end powder snow lay deep on the low-pitched roof and a frieze of icicles hung from the eaves. Skis and snowshoes stood by the doorway and smoke rose from the stone chimney as the Outing Club observed one of its great annual traditions.

There are some who will argue that of the thousands of Dartmouth graduates there is a very select fraternity made up of those who were active in the Outing Club during their college days. From this group come the alumni who make their way each year - drawn perhaps by memories of hillwinds and the still north - to spend the long New Year's week-end at the Ravine Lodge.

There are undergraduates from the college, and there are men who have carried the spirit of Dartmouth and its outing club to the far reaches of the North and of the Antarctic. There are alumni who bring their wives and children to taste again the tang of woodsmoke, carried on a winter wind and to absorb the stillness of the snow-covered mountain.

It is a week-end of stories about climbs on wind-swept ridges, of packing supplies to the old Moosilauke summit camp, of trail cutting in the early days of the skiing boom, of friendly cabins and lonesome paths.

It is a week-end of logs blazing in a huge fireplace, of kettles of hot spiced wine, of square dancing, of guitars and of folksongs being sung far into the night.

Why do people climb mountains?

The query came from one of our children. It was not the first time the question has been asked, nor will it be the last, for there are as many answers as there are people. We pondered a reply last week-end while skiing on the East Peak of Moosilauke.

From the Ravine Lodge the trail followed the headwaters of the Baker River toward Jobildunc Ravine. Fresh powder snow was everywhere, weighing down the branches of the evergreens. The path was well-packed; Hanover still produces a breed of skier able and willing to break trails to be followed later by those of us with softer muscles.

We were not alone. There were skiers ahead and behind, friendly and relaxed, enjoying the kind of fellowship of the trail that characterized the skiing fraternity before trams and T-bars made big business out of downhill-only. Sunlight poured into the frosty valley, although a few snowflakes sifted down, carried by the wind from a summit still sheathed in cloud.

We crossed the stream, paused to listen to the gurgle of water far beneath the snow. The path slanted upward away from the valley, following old logging roads and switchbacks. It was a clean, dry cold. Warmed by the climb, we took off a flannel shirt and slipped the.wool liners out of our mittens. The grade increased and the conversational banter that marked the first part of the climb ceased. The climbing wax we had rubbed into our skis held well, and the only sound was the slap of ski bottoms against snow.

In the valley big spruces had given a sense of seclusion. Up on the slope the larger trees had been cut. Trunks of ancient birches stood sharp against the sky and Christmas trees - the pulpwood of a future generation - poked through the snow.

We climbed slowly and steadily, gaining a second wind that brought with it that sense of physical well-being that comes when muscles and breathing are in tune. The Ravine Lodge could be seen far below. Ahead were the white scars marking the landslides above George Brook, and still higher swirls of snow and fast-moving clouds spoke of high winds sweeping across the summit ridge.

There came a pause for lunch: jam sandwiches, raisins, chocolate, and an orange. We ate standing in our skis; to have stepped out of them would have been to sink thigh-deep in the snow.

Then back to the climb, the narrow trail through the powdery snow, dense stands of evergreens, and on one side the slope dropping away to the valley of the Baker River and in the distance ranges of hills, changing from a winter brown to misty blues. Here, too, was the silence we associate with the higher slopes, a silence that is not a silence at all, but the softness of the wind rushing through trees high above.

We climbed in all for four and one-half hours, covering perhaps as many miles; a climb which led nowhere in particular but which brought us out eventually on a high shoulder of the East Peak with a view stretching to a distant and lonely horizon. At this altitude the trees were white with frost feathers; grey trunks, green branches and dazzling white ice against the deep blue of the sky. Far below a ribbon of white marked the road leading to the Ravine Lodge, and a plume of smoke suggested warmth within the lodge itself.

This was the stark beauty of winter at its finest. A good photographer can sometimes capture the colors, but no camera can record the cleanness of the air, the clarity of the sky, the body warmth stimulated by the climb, the sting of driven flakes of snow.

We adjusted the hoods of our parkas, tightened the hitches of our ski bindings, and pushed off down the logging roads up which we had just climbed. Here was no sweeping ski trail crowded with week-end skiers, steel edges chattering on icy corners. This was nothing more nor less than a series of relaxed glides through narrow lanes of powder snow bordered by spruce and balsam, a happy aftermath of the long climb upward.

An hour later we were back in the lodge drinking tea in front of the fireplace.

Why do people climb mountains? We promised to attempt an answer.

It seems to us that much of what man has created tends to defile the world of which he is a part. The fact that some of this may be inevitable does not mean that we must accept it happily. It is the mountains which remain for the most part unspoiled. It is possible to climb and leave behind the noise of traffic, the exhaust smoke and highways strewn with beer cans. Looking down, man and his handiwork are insignificant, and by the same scale his quarrels and his problems seem less important. It restores one's faith that a cleaner and better world lies within our grasp.

Maybe we speak too soon. Up there on Moosilauke last week-end, surrounded by those frost-covered evergreens, we reflected that man in his perversity has developed the means to saturate even the skies and the mountaintops with atomic pollution. It is not a happy thought.

But meanwhile the mountains remain unsullied. They may be pinnacles of granite, but they are also peaks of sanity in a world which needs perspective. The climber may not put this into words, but he senses it with his whole being as his pride of achievement blends with an appreciation of his personal insignificance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Very Old and the Old

February 1962 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Feature

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

FeatureELEAZAR WHEELOCKS, IN DIRECT LINE, STILL LIVE – IN TEXAS

February 1962 By SEYMOUR E. WHEELOCK '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1962 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1962 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY

Article

-

Article

ArticleFaculty to Raise Scholarship Standards

June, 1911 -

Article

ArticleCOMMITTEE CHOOSES 32 MEN FOR MANDOLIN CLUB

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Population

January 1939 -

Article

ArticleA Wall Hoo Wah for —

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleRecruiting Alumni Would Be A Serious Mistake

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1946 By John H. Minnich '29