THE COLLEGE OF TOMORROW—the one your children will find when they get in—is likely to differ from the college you knew in your days as a student.

The students themselves will be different.

Curricula will be different.

Extracurricular activities will be different, in many respects, from what they were in your day.

The college year, as well as the college day, may be different.

Modes of study will be different.

With one or two conspicuous exceptions, the changes will be for the better. But for better or for worse, changes there will be.

THE NEW BREED OF STUDENTS

IT WILL COME AS NEWS to no parents that their children are different from themselves.

Academically, they are proving to be more serious than many of their predecessor generations. Too serious, some say. They enter college with an eye already set on the vocation they hope to pursue when they get out; college, to many, is simply the means to that end.

Many students plan to marry as soon as they can afford to, and some even before they can afford to. They want families, homes, a fair amount of leisure, good jobs, security. They dream not of a far-distant future; today's students are impatient to translate their dreams into reality, soon.

Like most generalizations, these should be qualified, There will be students who are quite far from the average, and this is as it should be. But with international tensions, recurrent war threats, military-service obligations, and talk of utter destruction of the race, the tendency is for the young to want to cram their lives full of living— with no unnecessary delays, please.

At the moment, there is little likelihood that the urge to pace one's life quickly and seriously will soon pass. This is the tempo the adult world has set for its young, and they will march doubletime to it.

Economic backgrounds of students will continue to grow more diverse. In recent years, thanks to scholarships, student loans, and the spectacular growth of public educational institutions, higher education has become less and less the exclusive province of the sons and daughters of the well-to-do. The spread of scholarship and loan programs geared to family income levels will intensify this trend, not only in low-tuition public colleges and universities but in high-tuition private institutions.

Students from foreign countries will flock to the U.S. for college education, barring a totally deteriorated international situation. Last year 53,107 foreign students, from 143 countries and political areas, were enrolled in 1,666 American colleges and universities—almost a 10 per cent increase over the year before. Growing numbers of African and Asian students accounted for the rise; the growth is virtually certain to continue. The presence of such students on U.S. campuses—so per cent of them are undergraduates—has already contributed to a greater international awareness on the part of American students. The influence is bound to grow.

Foreign study by U.S. students is increasing. In 1959-60, the most recent year reported, 15,306 were enrolled in 63 foreign countries, a 12 per cent increase in a period of 12 months. Students traveling abroad during summer vacations add impressive numbers to this total.

WHAT THEY'LL STUDY

STUDIES ARE in the course of change, and the changes will affect your children. A new toughness in academic standards will reflect the great amount of knowledge that must be imparted in the college years.

In the sciences, changes are particularly obvious. Every decade, writes Thomas Stelson of Carnegie Tech, 25 per cent of the curriculum must be abandoned, due to obsolescence. J. Robert Oppenheimer puts it another way: nearly everything now known in science, he says, "was not in any book when most of us went to school."

There will be differences in the social sciences andhumanities, as well. Language instruction, now getting new emphasis, is an example. The use of language laboratories, with tape recordings and other mechanical devices, is already popular and will spread. Schools once preoccupied almost entirely with science and technology (e.g., colleges of engineering, leading medical schools) have now integrated social and humanistic studies into their curricula, and the trend will spread to other institutions.

International emphasis also will grow. The big push will be related to nations and regions outside the Western World. For the first time on a large scale, the involvement of U.S. higher education will be truly global. This nonWestern orientation, says one college president (who is seconded by many others) is "the new frontier in American higher education." For undergraduates, comparative studies in both the social sciences and the humanities are likely to be stressed. The hoped-for result: better under- standing of the human experience in all cultures.

Mechanics of teaching will improve. "Teaching ma- chines" will be used more and more, as educators assess their value and versatility (see Who will teach them? on the following pages). Closed-circuit television will carry a lecturer's voice and closeup views of his demonstrations to hundreds of students simultaneously. TV and microfilm will grow in usefulness as library tools, .enabling institutions to duplicate, in small space, the resources of distant libraries and specialized rare-book collections. Tape recordings will put music and drama, performed by masters, on every campus. Computers, already becoming almost commonplace, will be used for more and more study and research purposes.

This availability of resources unheard-of in their parents' day will enable undergraduates to embark on extensive programs of independent study. Under careful faculty guidance, independent study will equip students with research ability, problem-solving techniques, and bibliographic savvy which should be of immense value to them throughout their lives. Many of yesterday's college graduates still don't know how to work creatively in unfamiliar intellectual territory: to pinpoint a problem, formulate intelligent questions, use a library, map a research project. There will be far fewer gaps of this sort in the training of tomorrow's students.

Great new stress on quality will be found at all institutions. Impending explosive growth of the college population has put the spotlight, for years, on handling large numbers of students; this has worried educators who feared that quality might be lost in a national preoccupation with quantity. Big institutions, particularly those with "growth situations," are now putting emphasis on maintaining high academic standards—and even raising them —while handling high enrollments, too. Honors programs, opportunities for undergraduate research, insistence on creditable scholastic achievement are symptomatic of the concern for academic excellence.

It's important to realize that this emphasis on quality will be found not only in four-year colleges and universities, but in two-year institutions, also. "Each [type of institution] shall strive for excellence in its sphere," is how the California master plan for higher education puts it; the same idea is pervading higher education at all levels throughout the nation.

WHERE'S THE FUN?

EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITY has been undergoing subtle changes at colleges and universities for years and is likely to continue doing so. Student apathy toward some activities political clubs, for example—is lessening. Toward other activities—the light, the frothy—apathy appears to be growing. There is less interest in spectator sports, more interest in participant sports that will be playable for most of a lifetime. Student newspapers, observes the dean of students at a college on the Eastern seaboard, no longer rant about band uniforms, closing hours for fraternity parties, and the need for bigger pep rallies. Sororities are disappearing from the campuses of women's colleges.

"Fun festivals" are granted less time and importance by students; at one big midwestern university, for example, the events of May Week—formerly a five-day wingding involving floats, honorary-fraternity initiations, facultystudent baseball, and crowning of the May Queen—are now crammed into one half-day. In spite of the wellpublicized antics of a relatively few roof-raisers {e.g., student rioters at several summer resorts last Labor Day, student revelers at Florida resorts during spring-vacation periods), a new seriousness is the keynote of most student activities.

"The faculty and administration are more resistant to these changes than the students are," jokes the president of a women's college in Pittsburgh. "The typical student congress wants to abolish the junior prom; the dean is the one who feels nostalgic about it: 'That's the one event Mrs. Jones and I looked forward to each year.' "

A QUEST FOR ETHICAL VALUES

EDUCATION, more and more educators are saying, "should be much more than the mere retention of subject matter."

Here are three indications of how the thoughts of many educators are running:

"If [the student] enters college and pursues either an intellectual smorgasbord, intellectual Teutonism, or the cash register," says a midwestern educator, "his education will have advanced very little, if at all. The odds are quite good that he will simply have exchanged one form of barbarism for another ... Certainly there is no incompatibility between being well-informed and being stupid; such a condition makes the student a danger to himself and society."

Says another observer: "I prophesy that a more serious intention and mood will progressively characterize the campus ... This means, most of all, commitment to the use of one's learning in fruitful, creative, and noble ways."

"The responsibility of the educated man," says the provost of a state university in New England, "is that he make articulate to himself and to others what he is willing to bet his life on."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

Feature

FeatureLive Free or Die

June 1992 By Ernest Hebert Viking, 1990 -

FEATURE

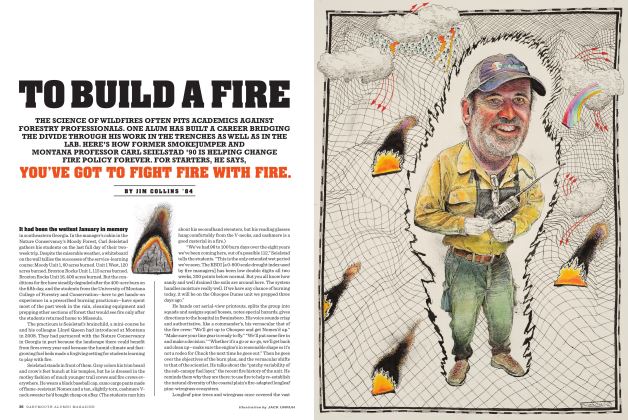

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeaturePARTYING: A PEER REVIEW

MAY 1992 By John Scalzi -

Feature

FeatureSoccer Mom

DECEMBER 1999 By Patricia E. Berry ’81