SAID AN ADMINISTRATOR at a university in the South not long ago (he was the director of admissions, no less, and he spoke not entirely in jest):

"I'm happy I went to college back when I did, instead of now. Today, the admissions office probably wouldn't let me in. If they did, I doubt that I'd last more than a semester or two."

Getting into college is a problem, nowadays. Staying there, once in, can be even more difficult.

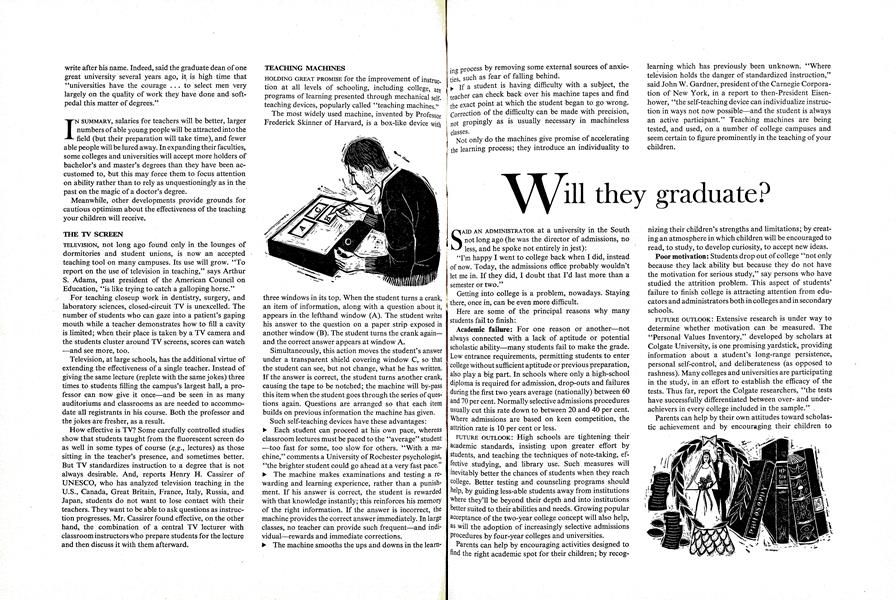

Here are some of the principal reasons why many students fail to finish:

Academic failure: For one reason or another—not always connected with a lack of aptitude or potential scholastic ability—many students fail to make the grade. Low entrance requirements, permitting students to enter college without sufficient aptitude or previous preparation, also play a big part. In schools where only a high-school diploma is required for admission, drop-outs and failures during the first two years average (nationally) between 60 and 70 per cent. Normally selective admissions procedures usually cut this rate down to between 20 and 40 per cent. Where admissions are based on keen competition, the attrition rate is 10 per cent or less.

FUTURE OUTLOOK: High schools are tightening their academic standards, insisting upon greater effort by students, and teaching the techniques of note-taking, effective studying, and library use. Such measures will inevitably better the chances of students when they reach college. Better testing and counseling programs should help, by guiding less-able students away from institutions where they'll be beyond their depth and into institutions better suited to their abilities and needs. Growing popular acceptance of the two-year college concept will also help, as will the adoption of increasingly selective admissions procedures by four-year colleges and universities.

Parents can help by encouraging activities designed to find the right academic spot for their children; by recognizing their children's strengths and limitations; by creating an atmosphere in which children will be encouraged to read, to study, to develop curiosity, to accept new ideas.

Poor motivation: Students drop out of college "not only because they lack ability but because they do not have the motivation for serious study," say persons who have studied the attrition problem. This aspect of students' failure to finish college is attracting attention from educators and administrators both in colleges and in secondary schools.

FUTURE OUTLOOK: Extensive research is under way to determine whether motivation can be measured. The "Personal Values Inventory," developed by scholars at Colgate University, is one promising yardstick, providing information about a student's long-range persistence, personal self-control, and deliberateness (as opposed to rashness). Many colleges and universities are participating in the study, in an effort to establish the efficacy of the tests. Thus far, report the Colgate researchers, "the tests have successfully differentiated between over- and underachieves in every college included in the sample." ,

Parents can help by their own attitudes toward scholastic achievement and by encouraging their children to and partying, it now includes study. And he who forsakes gardening for studying is less and less likely to be regarded as the neighborhood oddball.

Certain to vanish are the last vestiges of the stigma that has long attached to "night school." Although the concept of night school as a place for educating only the illiterate has changed, many who have studied at night- either for credit or for fun and intellectual stimulation- have felt out of step, somehow. But such views are obsolescent and soon will be obsolete.

Thus far, American colleges and universities—with notable exceptions—have not led the way in providing continuing education for their alumni. Most alumni have been forced to rely on local boards of education and other civic and social groups to provide lectures, classes, discussion groups. These have been inadequate, and institutions of higher education can be expected to assume un- precedented roles in the continuing-education field.

Alumni and alumnae are certain to demand that they take such leadership. Wrote Clarence B. Randall in TheNew York Times Magazine: "At institution after institution there has come into being an organized and articulate group of devoted graduates who earnestly believe ... that the college still has much to offer them."

When colleges and universities respond on a large scale to the growing demand for continuing education, the variety of courses is likely to be enormous. Already, in institutions where continuing education is an accepted role, the range is from space technology to existentialism to funeral direction. (When the University of California offered non-credit courses, in the first-named subject to engineers and physicists, the combined enrollment reached 4,643.) "From the world of astronauts, to the highest of ivory towers, to six feet under," is how one wag has described the phenomenon.

SOMB OTHER LIKELY FEATURES of your children, after they are graduated from tomorrow's colleges:

They'll have considerably more political sophistication than did the average person who marched up to get a diploma in their parents' day. Political parties now have active student groups on many campuses and publish material beamed specifically at undergraduates. Student- government organizations are developing sophisticated procedures. Nonpartisan as well as partisan groups, operating on a national scale, are fanning student interest in current political affairs.

They'll have an international orientation that many of their parents lacked when they left the campuses. The presence of more foreign students in their classes, the emphasis on courses dealing with global affairs, the front pages of their daily newspapers will all contribute to this change. They will find their international outlook useful: a recent government report predicts that "25 years from now, one college graduate in four will find at least part of his career abroad in such places as Rio de Janeiro, Dakar Beirut, Leopoldville, Sydney, Melbourne, or Toronto."

They'll have an awareness of unanswered questions to an extent that their parents probably did not have' Principles that once were regarded (and taught) as incontrovertible fact are now regarded (and taught) as subject to constant alteration, thanks to the frequent toppling of long-held ideas in today's explosive sciences and technologies. Says one observer: "My student generation if it looked at the world, didn't know it was 'loaded'. Today's student has no such ignorance."

They'll possess a broad-based liberal education, but in their jobs many of them are likely to specialize more narrowly than did their elders. "It is a rare bird today who knows all about contemporary physics and all about modern mathematics," said one of the world's most distinguished scientists not long ago, "and if he exists, I haven't found him. Because of the rapid growth of science it has become impossible for one man to master any large part of it; therefore, we have the necessity of specialization."

► Your daughters are likely to be impatient with the prospect of devoting their lives solely to unskilled labor as housewives. Not only will more of tomorrow's women graduates embark upon careers when they receive their diplomas, but more of them will keep up their contacts with vocational interests even during their period of childrearing. And even before the children are grown, more of them will return to the working force, either as paid employees or as highly skilled volunteers.

DEPENDING UPON THEIR OWN OUTLOOK, parents of tomorrow's graduates will find some of the prospects good, some of them deplorable. In essence, however, the likely trends of tomorrow are only continuations of trends that are clearly established today, and moving inexorably.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

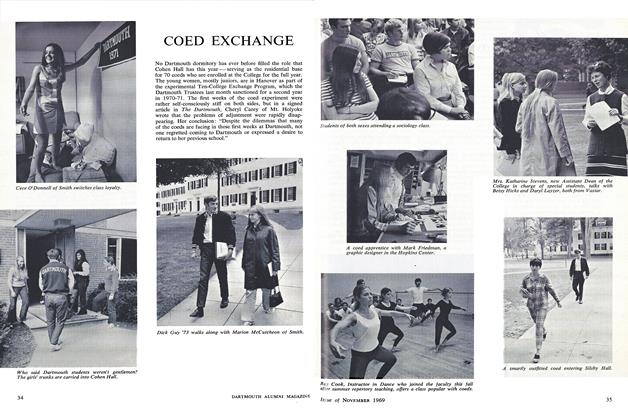

FeatureCOED EXCHANGE

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1971

JULY 1971 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureA College-Church Partnership

June 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

MARCH 1982 By George Kennan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham