Richard Hovey's Classmate and CloseFriend Has Lively Memories ofStudent Life of 80 Years Ago

DR. EDWIN HOWARD ALLEN '85 of 37 Hancock Street, Boston, Dartmouth's oldest living graduate, will celebrate his 100th birthday this month, on April 16. Dr. Allen, also the oldest living graduate of Harvard Medical School, was formerly Medical Director of the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company, with which he was associated for 49 years before his retirement in 1939.

Still mentally alert and in good health for a centenarian, Dr. Allen in recent years has been preparing his autobiography with the help of his son, Nathaniel D.W. Allen, to whom the ALUMNI MAGAZINE is indebted for the following excerpts having to do mainly with undergraduate days at Dartmouth. Dr. Allen was a fraternity brother and close friend of Richard Hovey '85, who figures in several of the reminiscences.

I WAS born in Alfred, York County, Maine on April 16, 1864, the fourth and last child of the Honorable Amos Lawrence Allen and Esther Maddox Allen.

Alfred, the shiretown, was settled in 1763, and in 1864 its population was about twelve hundred. The county courthouse was built in 1800; a few years later the academy, the first in the state, which prepared students to enter Bowdoin, the only college in the state at this time. Alfred, on the stagecoach route between Portland and Boston, was about thirty miles from Portland and about 100 from Boston. In 1864 stagecoaches were still running.

My father read law in the office of John Goodenow, son of Judge Henry Goodenow. Mrs. Goodenow was the daughter of United States Senator John Holmes, Maine's first Senator. He was one of the leading lawyers of New England and it is of particular interest to recall that he was opposed to Daniel Webster in the famous Dartmouth College Case.

I entered the high school in the fall of 1874 as the youngest pupil. At home I heard my father almost daily going over problems my older brother had in courses I had yet to reach, and in school similarly I heard recitations of the older scholars. Quite naturally the result was that studies and marks came easy to me, but in consequence deportment was another matter.

I elected to go to Bowdoin because my father had graduated from there in the class of 1860 with his classmate and close associate, the Honorable Thomas B. Reed, subsequently Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and also because my older brother was already there as a junior. Freshman year at Bowdoin on the whole was uneventful. It was Latin, Greek, and mathematics. There was no gymnasium and athletics were at a low ebb. Some of the students, but few freshmen, were invited to small whist parties. There were practically no public entertainments. In freshman year I joined the Psi Upsilon Society primarily because my father and brother were members.

When I became a sophomore we did very little hazing. However, the incoming freshman class of less than thirty seemed disposed to break college customs. Among the various episodes one freshman, Fred Smith, allowed his mustache to grow - which was clearly contrary to college customs. He was spoken to and it was shaved off but when he again allowed it to grow, this resulted in a committee to straighten the matter out. While not a member of the committee, I had been in his room somewhat earlier and therefore was one of those reported. The faculty took a serious view of the matter which we all felt was unduly harsh. The upshot was that eleven sophomores decided to leave college - one went to Williams, two did not complete the college course, and the other eight went to Dartmouth. These were Allen, Leigh, Goddard, Goodenow, Manson, Mooers, Hodgkins and Webb.

I went to Dartmouth alone in March 1883, took the examinations, was admitted, and in a few days the others came. After reaching Hanover and calling on President Bartlett, I called on Professor Parker and took an examination in Latin and then on Professor Richardson and took an examination in Greek. He had selected a Greek lyric anthology for the coming term and as I had written a translation of it while at Bowdoin it was consequently quite easy for me. We were not asked to take an examination in mathematics. Well, with the preliminaries over, late in the afternoon I experienced homesickness. Here I was a stranger in a hotel and knew not one of the students. I decided to go to a dormitory and ask for a Psi U.I rapped on the first door I came to and in response to my question Towle '85 came forward and said, "I am a Psi U." He and Bates 'B5 then took me to a house in Stump Lane to meet members of the class. It seemed that Dartmouth 'B5 had just had trouble. They had snowballed the house of John K. Lord, Professor of Latin, and in addition they had given him a horn concert. Unfortunately the Professor had pursued them and recognized a number of them, with the result that they were just returning from a brief suspension. Some twenty or more men in the room gave me a royal welcome and asked me to tell them what happened at Bowdoin. The last trace of homesickness had gone when I returned to the hotel. How important a warm and timely greeting can be and how happily one remembers it!

I secured a room in Dartmouth Hall, two flights up - the front-end room toward the north. In a few days Mooers came and remained with me as my roommate until graduation. The spring term opened a few days after we came. We were cordially received by the class, also by members of the faculty who met us.

Among the customs at Dartmouth was one not observed at Bowdoin - the stag dance. Dartmouth Hall was over one hundred feet long and once at least during the fall or winter the students, twenty or thirty or more, would appear in the long third-floor hall about bedtime. One played the violin - always the Virginia reel. A white handkerchief around the arm of every second student provided each one with a partner. A keg of beer was mounted about mid-way in the hall. Often a quart of whiskey was poured into the keg by one of the dancers - unobserved. As each couple came down the center toward the end of the hall the speed was so great that one lifted his right foot, the other his left, and when the feet hit the wall the sound was audible a considerable distance. My bedroom furnished the wall at one end and we wondered what the cause of those rhythmic blows might be. We had entered Dartmouth only a short time before and knew nothing about this custom. About midnight there was a rap on my door and we were invited to join them - which we did. After many of them were in that delightful physiological reaction in which they were indifferent as to whether school kept or not, someone came up the stairs at one end and shouted "Faculty!" No one investigated the alarm, but all ran into the nearest room and turned off the lights. Then they listened, cautiously investigated, and finding it was a practical joke, came out and the music and dancing continued until the beer was gone.

Early in junior year came the cane rush between the freshmen and the sophomores. The upperclassmen were on-lookers and offered first aid when necessary and dashed water on the contestants when requested to do so. The freshmen, naked from the waist up and thoroughly greased, stood in a solid square in front of the gymnasium. They had a piece of oak the length of a cane but much greater in circumference. This was held by several huskies in the center. The sophomores, also naked from the waist up and greased, marched about eight abreast the head of the column meeting the freshmen so as to push aside those on the right half of the column. The sophomores tried to break their way through to the cane; some of them were lifted up and over the heads of the freshmen. The first side to reach a designated goal with the cane won. Naturally the attempt was made to drag as many freshmen from the solid square as possible, and the grease forced the sophomore to put an arm around the neck of the freshman as the only means of pulling him from his associates. Those within the square became very hot and would shout, "Water, water!" We upper-classmen had pails of water and dippers and responded by throwing water into the air so that it would fall where requested. Now and then a contestant be came exhausted and we took him to one side and gave first aid. One or two physicians were present, but their services were not needed. There was no break for an hour or more, then the sophomores who were older, more determined, began to get the better of the contest. According to tradition some of the pushes lasted many hours.

At this point a few words about eating clubs. There were several, and in 1883 the price of board was $3.50 a week. Junior year I had board at the Crosby Club. .Mrs. Dixi Crosby gave meals to about twelve students, and did most of the cooking although she must have been sixty or more years old. Her husband was the surgeon Dr. Dixi Crosby, who had charge of the hospital in Washington where many Union soldiers were treated. Mrs. Crosby was a fine-looking woman, resembling in marked degree the portraits of Martha Washington, even to the treatment of her hair. She was a scholarly woman and spent her evenings reading the latest novels. Mrs. Crosby had been with her husband at the hospital. President Lincoln called every day when in Washington, to see the sick and wounded. She said he appeared very sad oftentimes after seeing the sick and wounded soldiers. After making his calls he usually sat down and talked with Mrs. Crosby. She told me that he not infrequently discussed family matters. He did not criticize Mrs. Lincoln, yet Mrs. Crosby felt that he did not rely on her judgment, and for that reason often asked how she would act in certain situations, particularly with reference to the children.

And now a word about my notebooks. I learned shorthand, the Isaac Pitman system, when fourteen - mostly because of disparaging remarks by my father as to my chances of ever learning it. Consequently I was able to take lectures verbatim. I was in fact indebted at least in part to my complete shorthand notes for one pleasure I vividly recall. The ablest and most brilliant man in our class - in fact, in my opinion the most brilliant man in Dartmouth College at that time - was Richard Hovey, the author of the famous Stein Song which, it should be added, was written after Hovey's graduation. We all knew that Hovey had unusual talent as a writer of prose and of poetry. When he was only eighteen or nineteen he knew as much about English poetry as the professor, partly because he quite often read all night to the occasional detriment of his other studies. Hovey also was a member of Psi U. He and I were friends and I think he talked with me oftener than with most of his classmates.

Professor Gabriel Campbell's lectures on the history of philosophy and on physiology I took verbatim, and about ten minutes before the recitation Hovey usually rapped on my door. "Hello, Dick," I would say, "going into Gabe's recitation?" With dignity Dick would answer, "I think not. I was not present at his last lectures and know little or nothing about the subject." Then I would give Dick a brief review of what Professor Campbell had said in his last two or three lectures and after I had finished Dick would say with a smile, "Well, I think I will go to the recitation." He would go into the classroom and sit up front where he was almost sure to be called upon. The Professor would ask him several searching questions, believing him not to be posted because of his absences. "Mr. Hovey" - he would stand up with marked dignity and for five or ten seconds would make no attempt to speak or answer the question. In that time he would mentally phrase his answer in beautiful English and then give an excellent recitation to the surprise of everyone. Each question he handled in the same way and the Professor usually gave up after about three. The result was that he obtained as good marks as I could and no one suspected that his answers were based on my five- or six-minute resume. Moreover he never forgot what I told him and never failed in an examination.

Perhaps I can add one or two anecdotes to the many which exist concerning Hovey. When the weather was at its worst in the spring Hovey was liable to have a cold and cough and remain a long time in his room. Classmates brought him his meals. One day Billy O'Brion, who had been bringing his meals to him for sometime, said to me, "Ed, let's cure Hovey." I asked how and Billy said, "We'll bring him for dinner food he hates, and practically nothing he likes." Of course Billy was satisfied that Dick was well enough to go out. It was boiled- dinner day and Billy selected vegetables he knew Hovey did not eat, nor did he eat corned beef. A small slice of bread was about all we carried to Dick which he would eat. When it was time for supper we called at Dick's room to take back the dishes. I stood in the hall and heard Billy say, "Why, Dick you didn't eat what we brought you." "No," said Dick quietly. "You didn't eat the corned beef or the vegetables." "No," said Dick. "Why, Dick, what did you eat?" asked Billy. "Crockery, by God!" But a cure resulted; Dick went to the club for his meals thereafter.

Probably the most interesting background ancedote of all has to do with how the Stein Song came to be written. Hovey had graduated from college and was in Paris, I believe, when the Psi U Society planned to hold a convention in some western city to which Psi U representatives from various colleges were invited. They asked him to give the oration, which was quite an honor since he had been out of college only a very few years. He accepted and came first as far as New York where he looked up some of his Psi U classmates. They were happy to see him and a group of them arranged a dinner to his liking, including beer which he enjoyed. After talking over old times they asked him whether he had written his speech for the convention. He replied, "No, I have not, but I have been giving it some thought. There are, however, one or two things that trouble me a bit. In the first place I do not have a proper suit for the place and in the second place I do not have money enough to get there." They laughed and told him that the money would be no problem but possibly the suit might be. One of them stood up and told him to try on his coat. It fitted quite well so he was told it was the same fit as a tuxedo he could have.

"Well," said Dick, "those two things being settled, I guess I will go to my room and write the speech." He was then asked what he planned to write about. He replied he thought he would make the first part about life in college. For the second part of the oration he would present his idea of the effect college should have on life afterwards. "Then," said Hovey, "I think I will write a poem to connect these two parts." So he spent most of the night writing the oration and read it to them the next day. It was a beautiful oration and quite naturally they then asked him about the connecting poem. "No," said Dick, "I haven't thought about it yet, but I will write it on the train." When he finally relaxed on the train he began to relive the pleasant evening. He began to think again of the warm friendships, the good dinner, the steins on the table, the reminiscences, and the wonderfully helpful spirit they had all shown him. Presently then he wrote, "For it's always fair weather when good fellows get together with a stein on the table and a good song ringing clear."

In 1884, my junior year, the College was small, consisting of about 250 students in the regular or classical department. Then every student knew every other student and often there were strong friendships. Graduation seemed surprisingly near and a question very often discussed was what to do after graduation? To go into business, law or medicine did not seem as attractive then as later. We rather thought we would pursue the classics or the modern languages by becoming teachers and then later perhaps professors or possibly authors. Personally I hoped to teach the modern languages and pictured to myself the delights of reading the masterpieces in French and German, of vacations and sabbatical years traveling abroad, and finally becoming a professor. ...

I remember the custom of an annual football rush between the freshmen and the sophomores. To win, a freshman had to bring the ball to the room of a junior while the sophomore had to reach that of a senior. On this occasion I happened to be in my room studying when I heard shouts of "Junior! Junior!" and to my surprise a full-blooded Sioux Indian burst into my room closely followed by half a dozen sophomores. Having won for his class, he stayed awhile and told me how he had run away from his tribe, adopted the name Eastman and had finally reached Dartmouth. After graduation he studied medicine and became the widely known Dr. Charles A. Eastman.

The manner of fighting fire was different then too. One Saturday late in junior year while recitations were going on we heard a fire alarm and a mad rush instantly ensued from all the recitation rooms. The fire was in the French settlement but threatened the whole village as the wind was strong enough to carry burning embers a considerable distance. In fact, at one time as many as thirty roofs were on fire. There was no fire engine, only two old-fashioned pumps manned by eight men. Just about every student responded and the faculty and citizens directed the fight. The students formed bucket brigades and kept putting out the fires as they started on the roofs, I was one of eight manning a pump which we pumped about ten minutes and then were "spelled" by a fresh eight About noon coffee and doughnuts were handed the students and the fire fighting continued until late in the afternoon. No lives were lost and the entire village was saved, but nine houses had burned in the French settlement. Needless to say, nobody went to bed very early that night and consequently a good number of students dozed in church next day. Dr. Leeds in his sermon pointed out how the forces of evil work twenty-four hours a day and appealed to the young in the church to be more vigorous. To emphasize his point he brought his right hand down on the Bible with great vigor and shouted, "Young man, wake up," and at least a dozen startled sleepers tried to.

As I look back over my college !ife, senior year, I think, was in a way not as pleasant as any of the previous years. This was natural primarily because the small classes resulted in strong attachments and the thought of separation had now become both truly painful and quite imminent. Two honors came to me unsolicited senior year which I recall with much pleasure. I was elected president of my class and in my fraternity was presiding officer one term. The studies were similar to those of junior year. During junior year I had formed the habit of reading late into the night too often and I continued to do so senior year. As a result, in May, I had a breakdown. I had just completed the college course and a little later was awarded a Commencement part and elected to Phi Beta Kappa. My Commencement part was a debate with the poet Hovey, Unfortunately I was unable to take the stage or to take my examination for honors in German and French. I did succeed, however, in securing the highest mark in German in the history of the College up to then. I was helped in this by a German in the class, Plapp, who gave me lessons in conversational German and in reading without translation. Naturally Commencement was a great disappointment to me. Later, as I still was unable to work, I could not accept a position to teach in a private school in Poughkeepsie.

Subsequently I decided to study medicine but was not well enough to enter the harvard Medical School until late in 1886. As I had been studying outside, this late start did not handicap me. Once again taking lectures verbatim in short- hand was a tremendous help and in senior year brought me final-examination marks of 97 in Clinical Medicine and !00 in Theory & Practice. Some years later shorthand again proved valuable when I worked with Professor Reginald H Fitz, under whom I had taken pathology, in the preparation of a medical textbook.

I received my medical degree in June 1889 and that fall opened an office at Hancock Street on Beacon Hill in Boston. However, shortly thereafter my father asked me to go to Washington, D.C., to act temporarily as a secretary to Mr. Thomas B. Reed, Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives. Largely because of the keen wit and extraordinary ability of Mr. Reed, this brief interlude produced many happy memories for me. My father likewise had an active career in Congress, serving ably for twelve years in the U. S. House of Representatives as a representative from Maine and often working closely with Mr. Reed. While in Washington I took part in the ceremonies in commemoration of the 100 th anniversary of the inauguration of George Washington, an impressive event which brought together the most representative group that had ever convened in the United States up to that time. Returning to Boston, I applied myself to the development of my practice and at first also did some work for the local medical societies. Shortly there- after I began to make examinations for the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company and it was fortunate that I had these several sources of income as the depression of 1893 was for a time quite severe.

In 1896 I was married to Linda Whitin Forbush, a very happy marriage for us both until her death in 1938. The next year we began housekeeping at my present address, 37 Hancock Street. With its marble front and circular staircase it has been listed as of historic value to the Beacon Hill area and is now over one hundred years old.

From 1890 on I gradually became more actively associated with the John Hancock Company. When I started they rented one floor of a building at the corner of Boylston and Washington Streets and there was one stenographer and less than 100 employees. In fact, the company was so small that a few years before serious consideration had been given to liquidation or merger. What a far cry from the present handsome 26-story building with its computers and thousands of employees. This growth was in large measure due to the constructive policies followed by the company, but I like to think that this was made possible in turn by the sound policies of the medical department. I was with the company 49 years and was appointed Assistant Medical Director in 1917. From 1923 until my retirement in April 1939 I was Chief Medical Director.

While I have no formula for long life other than the basic admonition of making sure you pick the right ancestors, I have always been a strong believer in regular but gentle daily exercise. I used to walk a good deal but this changed somewhat when I entered the auto age with the purchase of a Stanley Steamer in 1902. This car steered with a tiller and had a sort of front rumble seat.

I have one son, Nathaniel D.W., who was born in 1903 and when he was a baby, his mother and I frequently took him out in this car. If we were out when feeding time came, I simply turned a valve in the front of the car and heated his formula in the resulting jet of steam. He graduated from Harvard in 1925 and is now an officer in The First National Bank of Boston.

For my general health I took up golf about middle age and enjoyed it so much my wife used to jokingly suggest I ought perhaps to drop it for my health. Many pleasant games ensued at the country club with numerous friends and with my son who similarly enjoys the game. I continued to find this very beneficial exercise until I reached the age of eighty.

From then on I made a point of daily walks when in Boston, even in somewhat stormy weather, and in the summer time when at the family home in Whitinsville, Mass., I was quite active outdoors. This lovely old Victorian home is now about ninety years old. It has beautiful and extensive grounds and includes a large barn which still houses some sixteen carriages which had been used by various generations of my wife's family. Here at Linwood Grove we had numerous visitors and a number of particularly pleasant visits from Ralph Bartlett '89 who also lived near me for years in Boston.

Understandably, in the last five years I have been less active, but in season I continue to go to Linwood Grove in Whitinsville where I am frequently out-doors. I still watch television each day and have no restrictions on what I eat. I continue to enjoy what has been for me a long and full and what I hope is a worthwhile life.

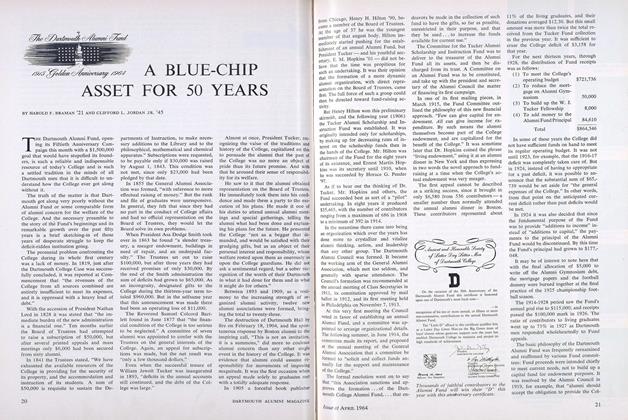

Psi U's in the Class of 1885. Dr. Allen is at the extreme left in the back row andRichard Hovey, in light suit, is seated in front of him in the second row.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

April 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNew Computer Network Open to Entire College

April 1964 -

Feature

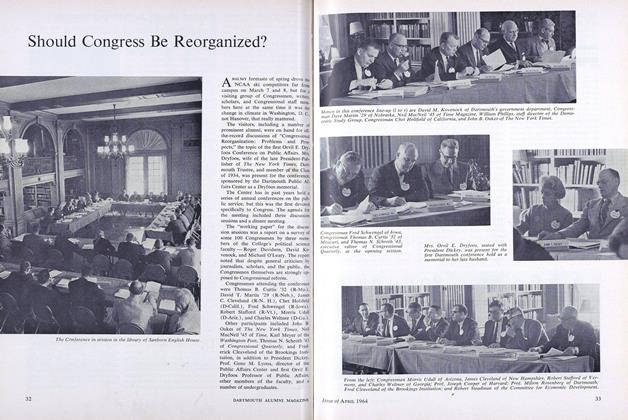

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

April 1964 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1964 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, HERMAN J. TREFETHEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

April 1964 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, PHILLIPS M. VAN HUYCK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JOHN S. MAYER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

MAY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAcademic Centers

June 1980 -

Feature

FeatureThe American Dream

JANUARY 1972 By A.T.G. -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HUCKTHE DISC

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC ZASLOW '89 -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

MARCH 1989 By Liz Walter '89