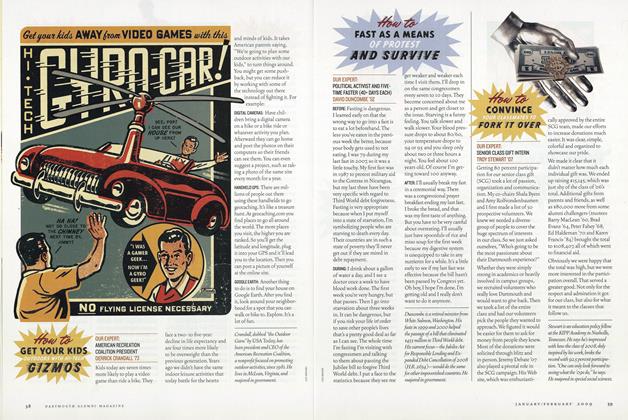

A Civil Action

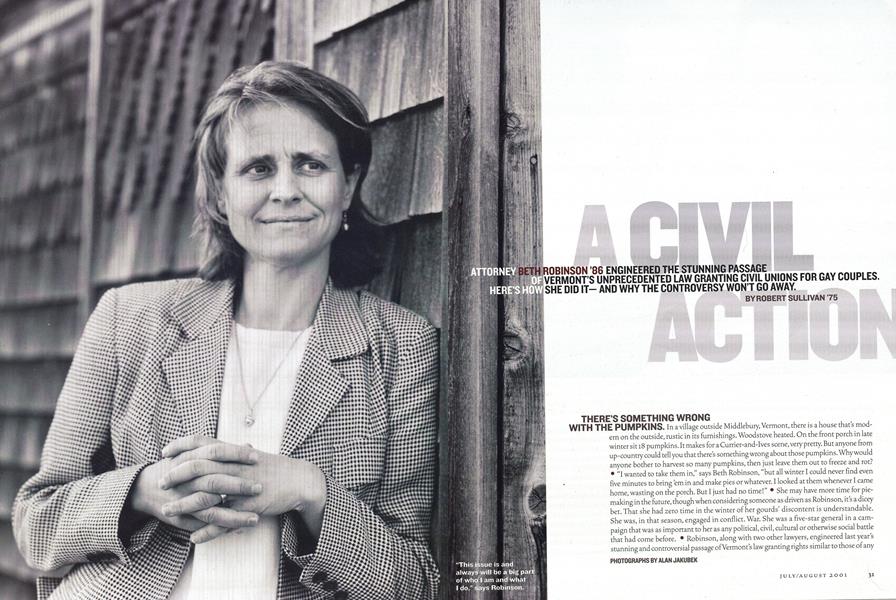

Attorney Beth Robinson ’86 engineered the stunning passage of Vermont’s unprecedented law granting civil unions for gay couples. Here’s how she did it—and why the controversy won’t go away.

July/August 2001 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75Attorney Beth Robinson ’86 engineered the stunning passage of Vermont’s unprecedented law granting civil unions for gay couples. Here’s how she did it—and why the controversy won’t go away.

July/August 2001 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75ATTORNEY BETH ROBINSON'86 ENGINEERED THE STUNNING PASSAGE OF VERMONT'S UNPRECEDENTED LAW GRANTING CIVIL UNIONS FOR GAY COUPLES. HERE'S HOW SHE DID IT-AND WHY THE CONTROVERSY WONT' GO AWAY.

THERE'S SOMETHING WRONG WITH THE PUMPKINS. In a village outside Middle bury, Vermont, there is a house that's modern on the outside, rustic in its furnishings. Woodstove heated. On the front porch in late winter sit 18 pumpkins. It makes for a Currier-and-1ves scene, very pretty. But anyone from up-country could tell you that there's something wrong about those pumpkins. Why would anyone bother to harvest so many pumpkins, then just leave them out to freeze and rot? • "I wanted to take them in," says Beth Robinson, but all winter I could never find even five minutes to bring em in and make pies or whatever. I looked at them whenever I came home, wasting on the porch. But I just had no time!" • She may have more time for piemaking in the future, though when considering someone as driven as Robinson, it s a dicey bet. That she had zero time in the winter of her gourds discontent is understandable. She was, in that season, engaged in conflict. War. She was a five-star general in a cam paign that was as important to her as any political, civil, cultural or otherwise social battle that had come before. • Robinson, along with two other lawyers, engineered last year's stunning and controversial passage of Vermont's law granting rights similar to those of any married couple to gay partners who choose to say "I do." On April 25,2000, the Green Mountain States legislators passed a bill allowing same-sex couples to enter into "civil unions," within which they are guaranteed a list of benefits and responsibilities—in the areas of child custody, family leave, inheritance, insurance—traditionally reserved for the traditionally wed. There isn't anything of its kind on the books in any other state.

Passage of the legislation marked the end of a hard five-year fight by Robinson & Cos. to achieve gay equality in Vermont, and the beginning of a bitter election-year backlash, in Vermont and else where, against anything that even looked like homosexual marriage. "Once the legislation was passed we had to work to protect it, and to protect those who had voted for it," says Robinson. "That's really where all my time went. Once the spirit of mutual respect in Vermont had deteriorated in the political season, we had to work constantly to counter the nastiness."

She's right about last year's vitriol—and we'll return to that colorful part of the Beth Robinson saga shortly—but passions have been percolating over this issue for years. Across the country, advocates for gay rights had been trying to get a state to sanction samesex marriage for most of the 19905, working equal time in legislatures and courts. In 1993 the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that denying gays the right to marry violated state law, so legislators changed the law. "Hawaii went to the brink but didn't quite put it over," Robinson says. Months later, a judgment in Alaska seemed to grant gay plaintiffs in a sex-discrimination suit the same rights as married folk. That decision only served to rouse the slumbering Yukon citizenry: In a referendum, voters put the kibosh on any further drift toward gay rights, joining what has grown to be two-thirds of all states that now formally ban homosexual marriage.

In Vermont, meantime, Robinson, a personal injury attorney with the Middle bury firm of Lang rock Sperry & Wool, LLP, and Susan Murray, a family-law practitioner at the same firm—both gay, both in longstanding relationships—were mounting an eastern offensive. fensive. In 1995 they cofounded the Vermont Freedom to Marry Task Force, an organization dedicated to lobbying and education. "In the early days it was a small handful of us doing a lot of talking," says Robinson. "We were talking to legislators if we could, but we'd talk to anyone. We were invited into Unitarian churches, then began to get into the Congregational churches and Episcopal churches." Robinson and Murray were trying to make the point that gay couples want the same securities that heterosexual couples enjoy, and, moreover, they wanted their relationships to be seen as legitimate, not illicit or aberrant. Murray, who in 1984 had argued the case for single-parent adoption before the Vermont Supreme Court, stressed that children of gay couples were unwitting victims of the status quo, as they couldn't enjoy "the security that other children have because their parents don't have any legal relationship to one another."

To be sure, Murray and Robinsons zeal, as well as the authority they brought to the subject, was informed by their personal lives. Asked if she might have seized upon this particular issue were she not gay, Robinson says, "It's hard to answer that because I don't have a parallel universe in which I m not gay. I have been struck by how many straight people have gotten involved with us along the way, but as for me, I'd say that experiencing the sting firsthand of being told I'm a second-class citizen is integral to what I'm doing. However, I'm also a lawyer. I believe in laws and think laws are there to create a better society. So both ways work for me. I think the question is not just how it feels to be a gay person on this issue, but how it feels to be a gay lawyer. Our cause is just, either way.

"Her passion about this is astonishing," says Nancy Wasserman 77, a gay Vermonter who has participated in open forums on the issue and watched from afar as Robinson maneuvered. It couldn't have just been legalistic. The drive, the energy, the tirelessness-it had to be personal."

THERE WAS, IN VERMONT'S CHURCHES in the mid-19905, discussion and debate, but no shout-em-down protests. 'At that point, civility ruled," says Robinson. "We were granted a cordiality and respect that Id still like to consider representative of this state. I started to sense a change when the lawsuit hit."

The lawsuit, Baker v State; came in 1997, when Robinson and Murray, with an assist from attorney Mary L. Bonauto of Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders of Boston, represented three gay couples who were suing the state for its refusal to grant them marriage licenses. In December of that year the Chittenden, Vermont, Superior Court ruled that same-sex unions simply fall outside the definition of marriage," but the three lawyers and their triumvirate of couples quickly appealed to the state Supreme Court. In November 1998 Robinson, then 35, delivered their argument before the bench, saying that under the Common Benefits Clause of Vermont's Constitution—which states that government must insure the common benefit of the entire community rather than protect advantages for any particular constituency—denying marriage licenses to gays was unconstitutional.

"Beth's finest hour was her argument before the Supreme Court," says David Chambers, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School who consulted with Robinson at various times during the civil-union campaign. Her oral argument was simply one of the finest I've ever seen. The justices were asking such interesting questions, and Beth was riveting—never looking at notes, always at the justices. She was extraordinarily well-prepared, and you could tell the justices were impressed. I have a tape of Beth, and I show it to the students in my family law class as an example of a breath takingly effective oral argument.

Effective perhaps, but the judges mulled it for a good long time more than a year. Finally, on December 20, 1999, the court issued a ruling tha twas stunning in its complexity. It said that,yes, same-sex couples were entitled to equal rights—but that it was the legislature s job to either amend the laws to reflect this, or to create a parallel struc- ture for gays. You might say the court passed the buck, but Robinson is more polite: "Let's say the decision, instead of ending the matter, started the matter. I can't deny that we were heartened by the court articulating such lofty principals, but this was counterbalanced by the remedy offered. We had to get back to work.

Murray and Robinson, with the blessing of their broad-minded partners in the firm, all but absented themselves from the regular day-to-day as the fight for gay marriage evolved from court case to crusade. "Our partners really took a hit because Susan and I clearly weren't generating much income for our pay, says Robinson. But this firm is very conscientious and public spirited. Pro bono still lives at Langrock."

With the courts inventive—some might call it screwy—ruling in place, the advocates' modus operandi changed. They no longer had to convince jurists with legalese, they needed to capture the hearts and minds of legislators. "Beth's legal strategy was brilliant, and now it had to shift overnight to a political strategy, says Chambers. "To watch her switch hats so quickly and deftly was amazing."

"Now we started to see the opposition really come out," says Robinson. "It became clear very fast that this was about November the election. Whichever way you came down on the question would impact your re-election chances. A lot of legislators were looking for options."

It was hard to compromise under the dictates as established by the Supreme Court: Let everyone marry, or find a new kind of marriage. The latter course was unpalatable to many gay activists; it looked, at best, like separate-but equal. Different terms were bandied about, and none of them gained much support until someone came up with "civil union."

"We wanted something that wasn't confusing, something that said more than 'domestic partnership,' " Robinson remembers. "'Civil union' had a certain dignity to it that softened the blow that we were not getting 'marriage.'"

Make no mistake, it was a blow. "As the idea of civil union' began to gain with some legislators who were having trouble on the issue, we had a couple of weeks of serious soul-searching as a movement," says Robinson. "Should we back this, or keep fighting for marriage? Finally, we let them know this was a term we favored, and that was very important to the fate of the bill."

The decision to back the idea of civil union—a phrase reeking of legalism and starving for a spiritual component—disheartened many homosexuals. "Beth is great, civil union' is not," says John Cloud, a gay journalist who covered the case for Time magazine. "Beth and I are in perfect agreement that there is a lot of cultural and social work to be done before everything's equal, and that things come in stages. But there are two ways to look at what was happening in Vermont. Most of the gay community thought the initiative went a long way toward giving gay couples equality. My view was that, in 40 years, we would look at this law and say, 'Plessy versus Ferguson.' It had the symbolism of an apartheid kind of thing."

"That's an absolutely foolish, foolish position to take," counters Chambers. "Social change of this sort almost never happens in one step."

What might someday be seen as the first significant move toward gay marriage came in April 2000, when, in a 79-68 vote, the Vermont House approved civil unions (the Senate was always seen as a lock). Reaction was swift. Much as a bearish electorate in Alaska had bolted from hibernation, many decorous citizens of Vermont read the morning headlines and said, "What!?!"

"The polls had consistently shown a state pretty evenly divided," says Robinson. "But as our opponents got louder, the polls seemed to tip to the anti' side, and we had a lot of work to do trying to protect legislators who had voted with us." Robinson puts it mildly when she says the other side turned up the volume. Every other week another interest group hung out a shingle—PROTECT OUR CHILDREN; TAKE BACK VERMONT; TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE. "We'd go to county fairs and they'd be there as well, with their own booths and displays," says Robinson. "It got tense." National political action committees sent shock troops to Vermont. The leader of the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue, Randall Terry, "showed up out of the blue and opened an office right there on State Street in Mont pelier," remembers Robinson. "He started threatening legislators that their careers were over. In the minds of the people, I'm not sure stuff like that hurt us. You just don't do those things here." Some people do. In Orange County the graffiti on the street signs read "Kill Fags," and, Robinson remembers, "during one forum in Franklin County the crowd got so out of hand shouting epithets that people were worried about a riot. One guy was there with a 10-year-old boy he was raising, and this other guy got up and shouted at the boy, 'Your father's a child-abuser!' Not pleasant."

Robinson went about her work in a more intimate fashion. "I've watched her talk before small gatherings of local folk in White River Junction," says John Crane '69, a librarian at the College who worked the issue alongside Robinson. "I've sat across a kitchen table and talked strategy with her. I've seen her talk to opponents, and address the Supreme Court. She's remarkably able to move calmly in different circles, always and effortlessly engendering a sense of respect in the person she's talking with. She clearly tailors her message for the audience, but she's always herself—and that's crucial because she's a wonderful personification of her message. The critical ical thing in this debate was to break down this us-versus-them mentality, to get the point across that this is about our common humanity. Beth personifies that, and she was the perfect leader for her particular issue."

"I'm not a person who usually does this sort of thing, but I found myself spending a day ringing doorbells up in Williston, Vermont," says Chambers. "That was all about Beth. She inspires that sort of dedication."

On election day Robinson's forces certainly didn't win, but neither were they routed. While Democratic Gov. Howard Dean, who signed the measure into law, survived a challenge by a foe of gay marriage, no fewer than 20 legislators who had supported the law were turned out. Moreover, nationwide exposure of the furor in Vermont caused aftershocks—negative ones, from Robinsons standpoint throughout the republic. In Nebraska and Nevada, for instance, on-the-books bans on gay marriage were approved with at least 70-percent support.

ROBINSON REMAINS OPTIMISTIC: "For the most part, the election in Vermont was a victory for us. We definitely lost a lot of really good people in the House, but I'm pleased to say not a single one of them said he or she regretted their vote. Some predicted we'd lose the Senate but we retained a pro-civil-union majority there. Most importantly, the exit polls showed about 60 percent of the people in favor of civil unions.

"This has been a mass coming-out party in Vermont the past couple of years," she continues. "A little scary for some, but finally with nice side effects." Robinson feels this is the way progress will finally be made and victory ultimately won—step by step, state by state. "That's the way movements unfold. In 1948,36 states piohibited interracial marriage. States changed, and then, in 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court finally took a case and struck down remaining strictures against it. We are where interracial marriage was then. One day gay marriage will be the law of the land.

Not so fast, says Walter Freed '74, Vermont's Republican speaker of the House. Freed says Robinson met with him (then the House minority leader) to discuss the issue before the vote, and that she was "very effective and energetic." But she didn't win his vote. Freed thinks the issue will be around for years to come. "There are national forces behind it," he says. Vermont is a test tube.

And yet...already, as the election-year am over vermont fades, there are subtle signs of shift. Advocates in New York and Rhode Island are forwarding gay-marriage bills this year, and in March an effort to forbid the blessing of same-sex unions in the nations largest Presbyterian denomination—a 2.6-million-member church based in Louisville, Kentucky—failed. In the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), at least, such unions can now be blessed. Elsewhere in the world, too, there has been social evolution. Sweden and Denmark now allow gay men and lesbians to register as partners and adopt children, and in the Netherlands on April 1 a new law took effect legalizing gay marriage.

"I'm proud to be a Vermonter," says Nancy Wasserman, who attended a civil-union ceremony—one of more than a thousand already staged—last December in Hardwick. It was a joyous affair when fellow '77 Linda Markin tied the knot with her partner of 2 years, Marie LaPre Grabon. Other Dartmouth classmates of Markins Robin Barnett, Jan Malcolm, Susan Dentzer—were in attendance, as were Judy Geer '75, Eileen Blackwood '80 and Lindas dad, Lawrence 52,11153. Markin and Grabon have four grown kids, two grandchildren and now—finally—a license that calls the family a union.

Over Memorial Day weekend John Crane of Baker Library and David Chambers of the University of Michigan, partners whose commuter relationship has survived the distance between the Midwest and their home in West Hartford, Vermont, entered into a civil union. "It's all a mystery to me," says Chambers. For lots of gay couples, wed always had these relationships and hadn't had to confront marriage. It is a little scary.

Later this summer, Robinson also will enjoy the fruits of her considerable labor and enter into a civil union with her partner of eight years, Kym Boyman, a physician. This one too will be a Big Green ceremony: Robinson, a native of Indiana, comes from an evergreen family. Her father, Robert Jr., is class of 1953. brother Robert III is a '75 and sister Barbara is a '76. "I came to Dartmouth because of my brother and sister, and once here I fell in love with this part of the country," says Robinson. "I love it up here. I love Vermont. I'm looking forward to returning to a more normal, sedate life here getting back to my practice, my house, my garden. "My pumpkins."

"This issue is and always will be a big part of who I am and what I do," says Robinson.

The political season in Vermont was anything but civil, as the civil-union legislation polarized the state. "We had to work constantly to counter the nastiness," Robinson says.

"THIS HAS BEEN MASS COMING-OUT PARTY IN VERMONT THE THEE PAST COUPLE YEARS," SAYS ROBINSON. "ONE DAY GAY MARRIAGE WILL BE THE LAW OF THE LAND."

ROBERT SULLIVAN is a senior editor at Time magazine. He wrote aboutphoto journalist James Nachtwey '70 in the June 2000 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July | August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Feature

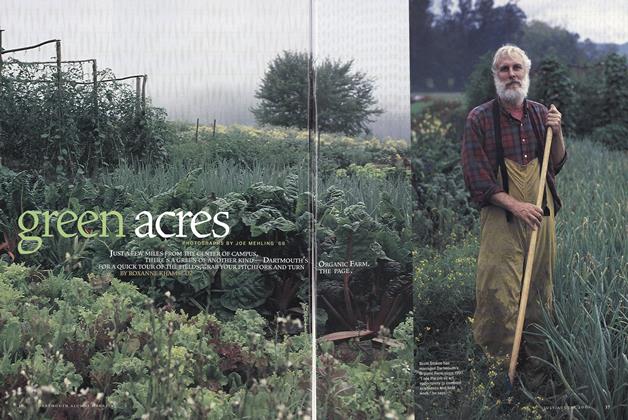

FeatureGreen Acres

July | August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

Feature

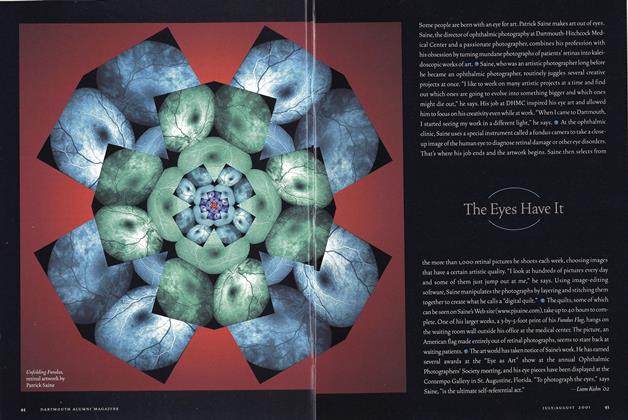

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July | August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July | August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July | August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2001

ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

December 1990 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Sports

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May/June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

FeatureSoviet Union

Sept/Oct 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July/August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEHe Wept Alone

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75