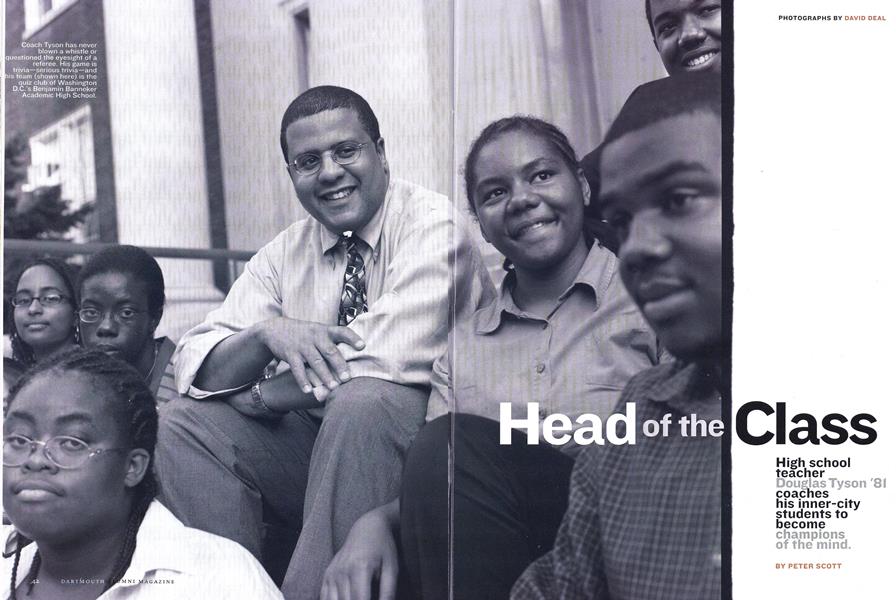

Head of the Class

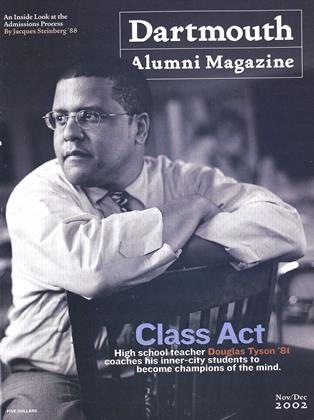

High school teacher Douglas Tyson ’81 coaches his inner-city students to become champions of the mind.

Nov/Dec 2002 PETER SCOTTHigh school teacher Douglas Tyson ’81 coaches his inner-city students to become champions of the mind.

Nov/Dec 2002 PETER SCOTTHigh schoolteacherDouglas Tyson 81coacheshis inner-citystudents tobecomechampionsof the mind.

almost 4 p.m. on a recent spring day, and Douglas Tyson, a teacher and a successful coach in the Washington, D.C., public school system, is ready for practice. The 43-year-old Tyson has spent countless hours preparing his championship teams. But unlike most coaches, he's never blown a whistle. He has no interest in wind sprints and warm-ups. As coach of Benjamin Banneker Academic High School's It's Academic quiz bowl team, he just wants answers—and he wants them fast.

Named for a TV quiz show now in its 41st year on a local Washington affiliate, It's Academic is a demanding extracurricular activity. Top high school teams travel the East Coast to play in up to 30 College Bowl-style tournaments a year.

During the past decade Tyson has defied long odds to build Banneker into a powerhouse. The 1996 squad established a record for points scored in a single televised game, and in 2001 a Tysoncoached, Banneker-led team representing the District of Columbia beat the best from 40 other states and territories to win the Panasonic Academic Challenge, the Super Bowl of scholastic quizzes held each year in Orlando, Florida. This past year the team, in addition to making its way to the semifinals of the Panasonic event, organized and sponsored its own 58-team tournament, a "major undertaking," according to Tyson.

The victories over prep schools and science academies are even more impressive when one considers that Banneker is a crumbling inner-city school where, Tyson estimates, "Thirty to 40 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced lunch" and 99 percent are minorities.

Tyson, who teaches chemistry and biology, uses It's Academic to expand his students' limited curriculum and expose them to subjects such as existentialism and expressionism. Another goal is to teach black students that they can compete—in school and in life. "It's a major-league commitment," Tyson says. Tournaments are day-long affairs, and they're held three times a month. Practice is ongoing.

Barging into his science classroom with an armful of snacks and a collection of brain-busting questions, Tyson wastes little time. Because of a concurrent Advanced Placement exam, today's turnout for practice is low, but the foghorn-voiced Tyson keeps the energy level high. He pauses briefly to tease a young woman who has been admitted to Harvard, jocularly recommending the green hills and pastoral beauty of his alma mater over the urban chaos and congestion that awaits her in Cambridge. She takes the good-natured ribbing in stride.

The students, mostly African-American males, race to ring in on a multi-user buzzer system. As he munches cookies, Tysons reactions swing from mock exasperation to real euphoria, with a little conspiratorial scheming thrown in to remind the students that he's on their side.

"See the problem, then solve it systematically—do you follow me?" he asks a young math whiz. "Remember," he tells another player, "use speed to ring in. Then take your time to answer the question." Tysons admonitions are as relentless as his questions about math, science and the arts. "Go with the obvious. Socialist presidential candidate has to be Eugene Debs. Do you follow me?"

Tyson had not spent one second as a teacher or student in a public school before arriving at Banneker in 1989. A native of New Haven, Connecticut, he attended private schools before going to Dartmouth, where he majored in math and biology. Then he earned a masters in biochemistry at Yale. His only teaching experience was in a summer program at Phillips Andover Academy, the noted private school in Massachusetts.

Tyson moved to Washington in search of a job at another private school. But before he could stock up on blue blazers, friend Greg Henderson 'BO encouraged Tyson to contact Banneker, which he visited "on a lark." That visit evolved into a 14-year classroom career that has earned Tyson national education awards in science and math from the likes of Tandy, GTE and Sallie Mae.

It was in Tysons first semester at Banneker tha the was asked to supervise the It s Academic team. "I had no idea what I was doing," he says. The team had no practice materials and their buzzer "system" consisted of a wooden stick with an old doorbell that constantly shorted out. And though Tyson never received any overt pressure, the message from the top was clear—as the only D.C. public school participating in Its Academic, Banneker needed to be a success.

At his first tournament Tyson and his fledgling team experienced double disappointment. "We had our heads handed to us," he remembers. But he was less discouraged by the results than by the chilly reception from the other coaches and students. At the time, It's Academic was mostly confined to suburban schools, and the competitors "weren't used to seeing children who looked like ours or coaches who looked like me," he recalls.

Tyson attempted to network among other coaches for tips on improving his program but was met mostly with blank stares and cold shoulders, a racist response he attributes to the then-lily-white world of high school quiz clubs. But Gerald Green baum, a coach from Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Beltsville, Maryland, reached out to Tyson and clued him into the realities of competition—summer camps, reference materials, tactics and strategies. Green baum scrounged up a buzzer system and advised Tyson to seek counsel from Sue I ken berry, a coach and history teacher from Georgetown Day School, a private school in Washington with a largely Jewish student body.

"I've never seen anything like the attitude of those early kids," recalls I ken berry. "They would lose and lose, but they never whined. They just said, 'We'll get better.' " And they did. Tyson's program began a steady climb to respectability and excellence.

Once they'd cemented their friendship, Tyson and I ken berry began to combine the all-white Georgetown Day and all-black Banneker squads for joint practices and scrimmages. The two teams traveled to tournaments together and attended each other s matches. "You see very quickly a nice public-private partnership among the children, with both sides benefiting," says Tyson. "It shows that it can be done without force or coercion." It was two Jewish George town Day students who combined with four African-American students from Banneker to lead the D.C.-area team to a first-place finish over the nations top teams in the 2001 Panasonic tournament.

Another milestone occurred in 1999, the first year that an all male Banneker team appeared on TV. Tyson notes that only 5,000 African-American males score higher than 1000 on the SAT each year, "an incredibly sad fact." Think, he adds, "how important It's Academic is in relation to that...to put African-American boys on television and have them win!"

For many of his students, Tysons influence extends beyond high school. At least 15 of Tysons Banneker pupils have attended Dartmouth, with four currently in Hanover: Karm Mohsen '03, Donald Jolly 04, Rena Coombs '05 and Emerald Elder '05. Of these four, all but Elder participated on Tysons Its Academic team.

Tyson points to several Dartmouth professors as his own key influences. He calls math'professors Dwight Lahr and Reese Prosser "gifted teachers." Lahr, he adds, was a "tower, a professional. He liked mathematics! He could convey that to me and I didn't think it was dorky. I'd like to do that for these African-American kids." Tyson is active in recruiting minorities to Dartmouth. He's a founding member of Dartmouth Bound, a program spearheaded by Gary Love '76 that flies minority students who are prospective Dartmouth applicants to Hanover at the start of their senior year in high school.

For his efforts at Banneker, Tyson was named a person of the year by Washingtonian magazine. But the personal laurels matter less than what his students have accomplished. Tyson cherishes a memento from an earlier Banneker-Georgetown Day tournament trek to Florida. A 1998 photograph shows his charges "out in the rain, on the ground doing push-ups," he says. "It doesn't matter if they're black, white or Hispanic. I always kept that picture, because if you ask me what epitomizes the partnership between Georgetown Day and Banneker, there it is right there: Kids doing the things that kids do."

In addition to the overtime spent drilling his teams and preparing students for rigorous Advanced Placement exams, Tyson has also became a tireless fundraiser to secure the future of Banneker s It's Academic tradition. Donations now ensure that his teams can travel and buy what they need to stay competitive.

As his team's long practice concludes—"Who discovered streptomycin?" "What is 216 to the two-thirds power?"—Tyson reviews some details with his students. "Rogers, do you have money for the bus? Robinson, do you need my cell phone to call home? Hey, guys, sit down and study. If we play scared, we're not going to windo you follow me?" Indeed they do.

Coach Tyson has never blown a whistle or questioned the eyesight of a v referee. His game is trivia—serious trivia—and his team (shown here) is the quiz club of Washington D.C.'s Benjamin Banneker Academic High School.

Tyson initially attemptedto networkamongother coaches for tips onimproving his programbut was met mostlywith blankstares and coldshoulders, a racist responsehe attributes to the then-lily-whiteworld ofquiz clubs.

Tyson expands hisstudents'limitedcurriculum by exposing them to subjects such as existentialism and expressionism. Another goal is to teach black students that they cancompete—in school and in life.

PETER SCOTT is a freelance writer who has written for Forbes FYI, The Wall Street Journal and Playboy. He lives in Washington, D.C., and worksfor Morgan Stanley in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

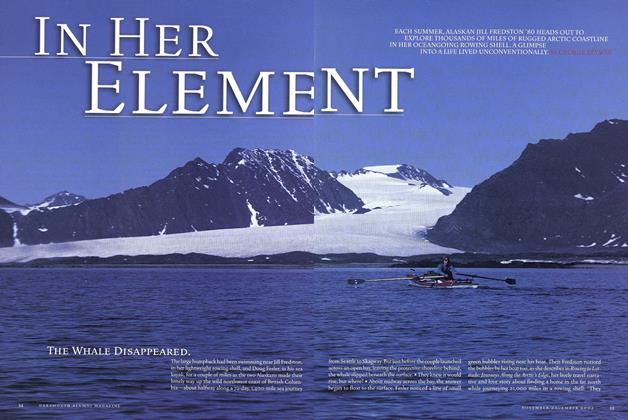

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThorne Smith 1914

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

OCTOBER, 1908 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureHow to Buy a Mattress in India

December 1987 By Elise Miller '85 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

APRIL 1982 By Rob Eshman