GO SOUTH IN BIG GREEN STYLE" shouted the ad for a leading Hanover haberdashery, while a lissome bathing beauty beckoned, with the promise, "I'll be seeing you." On March 4 it was enough to make Earnest T. Booker himself throw up his hands in despair. Eastern skiing held no promise at all, so if you didn't have a thesis to finish, you probably wouldn't have stuck around for spring vacation.

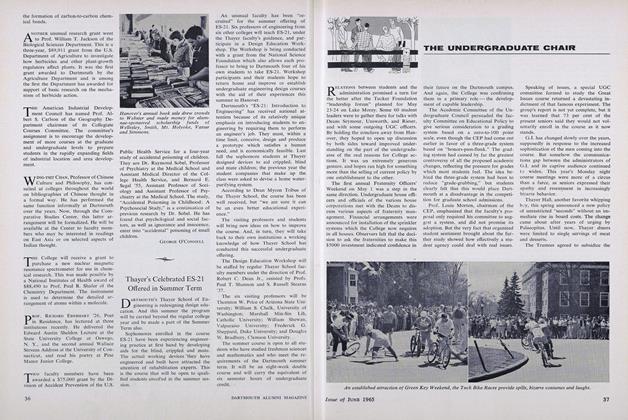

March came in like a lamb this year. A week of temperatures in the 60s brought exam crammers out-of-doors, craving the "beneficial rays," and the disgustingly sparse snow cover disappeared without a sign of schlump. In local store windows, bermuda shorts, tennis shoes, and frisbees threatened to crowd out the ski bargains, and a New York mail-order house was pushing a sweatshirt imprinted with "Long Live Pussy Galore" as the hottest thing on the beach. "Your whole frat will want them," the ads said, but local reaction was pretty generally negative.

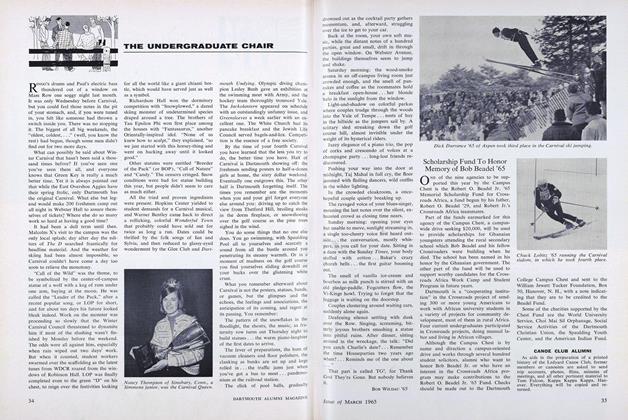

Spring vacation on the three-term system still comes somewhat ahead of most other school recesses so that, with no holidays to draw you home to the family, you are free to follow the melting snows to the sea, or to turn to the Western mountains where this year Aspen got more snow in five days than most Eastern resorts had had all winter.

As winter term dragged to a close, an appropriate chill descended again, and with the actual onset of exams, one knew that if spring was springing anywhere, it wouldn't be in Hanover. But when the orgy of booking finally came to an end, once again the windows were thrown open to let out the rock 'n' roll that always seems to sound the promise of good times for our generation here. Nobody packed for this trip; you just grabbed a few clothes, tennis racket, or skis, cashed a last check (if you were lucky enough to have a few dollars left), piled into the car, and moved out.

Once you were on your way, you covered the miles so fast that afterward you could hardly recall the trip, but for the face of a plain-Jane waitress in some Nebraska diner, or the laconic drawl of the attendant at some all-night gas station in the Carolinas. Driving, stopping only for gas and another map, trying to sleep, or staying awake to talk to the driver, eating hamburgers you weren't hungry for, hating to look at yourself in the restroom mirror - afterward it all seemed just like one long and sleepless night, but there you were, awakening to the early morning sun on the slopes of Aspen, or to the sound of boats on the canal in Lauderdale.

There were many ways of cutting expenses. In Florida, eight fraternity brothers slept on the lawn of another's house. Bologna sandwiches packed easily, and tasted great with beer for lunch and dinner, and in between times Mrs. W —'s famous breakfasts carried the day. In Vail, six of you rented a trailer and did all your own cooking. When money got low, you mopped floors, or shovelled snow off the roofs, or you could pack the slopes for two hours and earn a day's lift ticket.

BUT while thousands reveled in the islands or in the western mountains, the important "action" this spring was in Alabama, and hundreds of collegians from all over the country flocked into Selma and Montgomery, including at least five from the College.

John Kunz '65, Ken Berger '66, and David Samuel '67 were listening to the news from Selma as they cruised through southern Georgia, bound for Ft. Lauderdale, and in the same instant, Kunz recalls, "We all looked at each other and asked 'why not?' " By this time they were almost in Jacksonville, so the side trip took them some thousand miles out of their way. If they went in as tourists, they obviously came out deeply stirred by a new knowledge of what "the movement" was all about.

"There were a lot of things to think about right after we decided to go," Samuel explained. "We had to consider whether or not to take the car into Alabama, and then we thought of excuses we could use merely for being there if we were challenged. You could feel the antagonism at every filling station when the guy would see those Pennsylvania plates. We also took the precaution of calling one of our parents, just so someone would know where we were in case anything happened."

The three students had no idea how they would be received, even by civil rights workers in Selma, since they didn't intend to stay more than a couple of days. "When we rolled into Selma late on Saturday night, the main part of town seemed to be under siege," Samuel recalled in an article for the family-owned Delaware Valley (Pa.) Advance. "State troopers manned every corner of the deserted streets. But in the Negro district, the streets were jammed with cars and people, while National Guardsmen looked on from armored cars and jeeps. People were coming in from all over the country - just dropping in, but one very old Negro came up to us and said, 'God bless you. God bless you that you are here.' They couldn't believe that so many would have come all the way down from the North for them.

"The atmosphere was so tense that even the joking was sort of nervous. Everyone was so caught up in the spirit of the march that it became deadly serious. We never thought about the ordinary pleasures of vacation. Wallace's charge about immorality among the rights workers is outrageous; nobody was even eating very well, much less doing any drinking."

The three men sacked out on the altar of the First Baptist Church, a block from the Brown Chapel, before joining the crowd, estimated at 10,000, for the first day's march out of Selma. What impressed them most was the discipline and organization of the marchers, who were accompanied by a stream of communications vehicles, ambulances, and even trucks with lavatories aboard.

After the first day, of course, the march was limited by court order to 300 persons, and Samuel, Berger, and Kunz took off for Florida. Looking back on it afterward, Kunz felt that "even in one day we accomplished something by being there; certainly I think we learned something about practical politics from those local kids that we'd never experience anywhere else in the country."

None of the trio now plans to return to Alabama, or to continue in civil rights work at that level, but their comments describe the cautious involvement which more and more students are accepting as a result of recent events in the South. Samuel described it as "fulfilling my role as a responsible citizen, no more than that. It's just a new form of political participation. But probably the greatest discovery has been that we can effect meaningful change."

CAMPUS elections went over with a soft thud last month as a mere 49 per cent of the student body turned out to vote for class officers, members-at-large of the Undergraduate Council, and members of the UGC Judiciary Committee.

As The Dartmouth pointed out, "less than half the students voted because.(1) few people knew or cared who was running until they read [the paper on election day], (2) there was little or no advance publicity on the fact that elections were being held, (3) there were no issues, ideas, or 'personalities' on which the students could make a choice, and most important, (4) the offices to be filled hold little responsibility."

The same men usually divide both class and College offices among themselves anyway, but the real leaders, the presidents of the UGC and the Interdormitory and Interfraternity Councils, and the chairman of Palaeopitus, are all elected on the inside. Thus the average student who is not interested in going into politics (or public service, depending on your viewpoint) can do nothing with his vote except return the same men to places on the Undergraduate Council, and hope that real leadership somehow crystallizes.

Painful Evaluation Time is here again for the outgoing UGC, and it promises to follow the pattern of recent years. It is said that the strongest feature of Dartmouth student government is that it knows its own limitations, and it is true that each year the solons are terribly frank about how little has been accomplished.

But one should not get the idea that any kind of crisis exists, because in fact the apathy is so pervasive that hardly anyone cares enough to wonder at it. But the UGC itself may soon decide that its annual search for issues has been needless as well as fruitless, and thus it might as well drop even the springtime optimism. Then the day may not be far off when a surprise motion in the UGC for self-abolition will surprise no one by sweeping the whole structure away.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

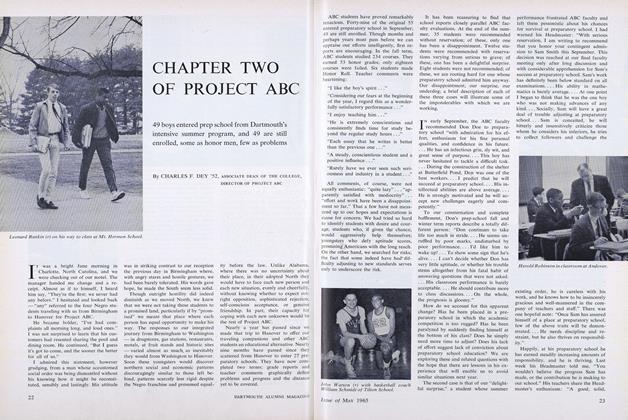

FeatureCHAPTER TWO OF PROJECT ABC

May 1965 By CHARLES F. DEY '52, -

Feature

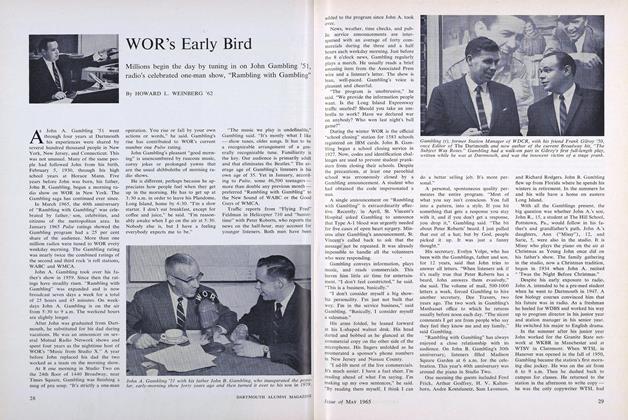

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

May 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

May 1965 -

Feature

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

May 1965 -

Article

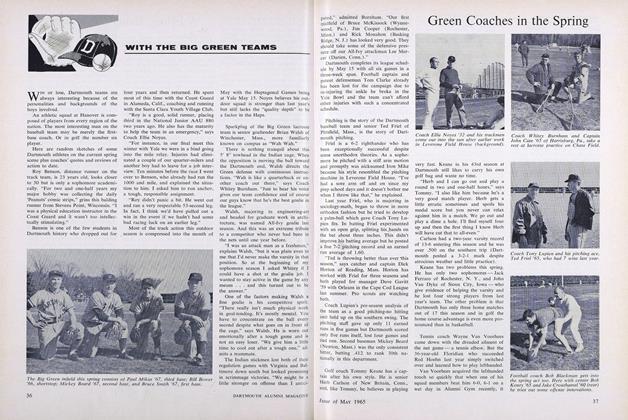

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

May 1965 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, ROBERT H. LAKE

BOB WILDAU '65

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65