THE Boston Record-American was having a slow time of it one night last October; slow, that is, until somebody, perhaps idly leafing through back issues of The Harvard Crimson, came upon an almost-too-good-to-be-true sex scandal.

Origin of the "scandal," which the wire services flashed across the country and which even pushed its way onto the front page of The New York Times, was a letter written to the Crimson by Harvard's Dean almost a month before the story "broke." The letter expressed concern that students were using the privilege of entertaining dates in their rooms as a license for licentious behavior.

The whole thing appears to have been a squall in a demi-tasse, and one theory in Hanover maintains that it resulted from a managed newsleak engineered to put some "bizazze" into Harvard's image.

The increased interest in undergraduate sex mores produced by the "scandal" was reflected at Dartmouth, where several inquiries as to the exact position of the College administration on life among the sexes were received.

Some of these resulted from what Dean Thaddeus Seymour has called "Dartmouth's position as the snowcapped Fiji Island of the North," meaning that "while everyone knows pretty much where it is, no one is quite sure what goes on there." Just exactly what does go on here becomes an especially pertinent topic with Winter Carnival (February 7-9) just ahead.

Well more than 2000 young ladies are expected to arrive on the Hanover Plain for Carnival this year. The College maintains a full-time staff to assist students in obtaining rooms for them, specially scheduled busses will ferry them in, and chances are there will be more of them this year than ever.

"There are more each year," says Mrs. Robert K. Hage, College hostess, "and not just for the big weekends. Our biggest weekend this year, so far as finding rooms was concerned, was Brown weekend last fall. Why the increase? I couldn't say for sure. Easier transportation is one reason, and freshmen are having more dates for another."

What will they do when they get here? They'll attend the plays and concerts; assist in putting the finishing touches on the snow statues; help at "cheering when the teams in Green appear"; admire Hopkins Center's architecture, exhibits, and galleries; do some "twisting" either at the College-sponsored dances or fraternity parties - both will feature rock 'n roll bands - and in general they'll enjoy the coolest, coldest, oldest, and perhaps best-known college weekend in the U. S.

On Friday and Saturday nights students will be able to entertain dates in their dormitory rooms until midnight and 1 a.m., respectively. The standard of conduct expected is spelled out in The Dartmouth Student Handbook given to each student in September: "Gentlemanly conduct is expected at all times; promiscuity constitutes a violation of College standards and regulations." Enforcement is accomplished by the campus police, who are reinforced by extra officers on big weekends, and by dormitory and fraternity officers.

"We don't regard ourselves as the keepers of anybody's morals," says Proctor John F. Carey Jr. "We just enforce the College regulations. An officer will go into each dorm after the hours for women guests are over. If he hears a party still going on, or if he is informed by one of the dorm officers that a woman guest is still in the dorm, he will knock on the door, identify himself, and ask to be admitted. We don't open closed doors except in an emergency, such as a fire. If a girl is still in the room, the officer will ask that she be escorted out.

"Cases of after-hours violations are turned over to the Interdormitory Council Judiciary Committee for disciplinary action. Most of the time - and these cases are rare to begin with - it's just a case of an honest mistake as to the hours for that night."

Such cases serve to raise the question of just how far the College goes in providing complete enforcement of its regulations. Dean Seymour has explained that the regulations are "primarily to communicate a standard of expectation." How many take advantage of the College's good nature no one can say, but probably it is surprisingly few. As Dean Seymour has said, "The situation is certainly better than everyone likes to think it is. We believe that responsibility for social conduct should be part of the Dartmouth educational experience, and that if the administration were to take on the responsibility for absolute enforcement of a certain standard of behavior, we would subtract from the value of a Dartmouth education. Our experience has been that students here do not abuse their privileges."

The undergraduates back this up. "Having a date up here," one explained, "is a complicated and expensive process, and when she's here you're stuck with her for the whole weekend. So you invite a girl that you especially like, and the problem of 'promiscuity' doesn't come into the question."

"When you've got 3000 guys up here with dates," said another, "there's going to be a little of everything going on, but this picture some people have of a wild, flat-out-of-control show being put on here - well, it's just not the way things are."

"No, there isn't much 'promiscuity', and you'll hear a lot of reasons why not, but the basic answer is that the students here , though they may not admit it, are a pretty sound group."

There are isolated incidents of "flagrantly ungentlemanly conduct," admits Proctor Carey, but they are so rare as to be "negligible." "I am convinced," he says, "that the standards of Dartmouth students are far higher than those of society in general."

And these isolated incidents are nothing new. Alumni concerned as to whither the younger generation goest will be pleased to hear that not for many years — 33 to be exact — have there been goings-on in Hanover to match those legendary escapades which led to the banning of Spring Houseparties following the vernal festivities of 1931. There are still no Spring Houseparties.

In all, the situation today is a reward for the faith and confidence expressed by "'The Special Committee on Rules" of 1947 which first allowed female guests into dormitory rooms. The limit they set was 7 p.m., because in their opinion neither the "sense of responsibility . . . nor a system of [student] government" existed that would make possible a regular extension of the hours. But it was their hope that "a more liberal rule" would be added as soon as the attitude and actions of the student body justified it. Since then the students have been judged to merit further confidence and the dormitories are open to women guests until midnight on all Saturday nights, and special extensions are granted on big social weekends — usually twice a term — as determined by the Interdormitory Council.

"The dormitory committees are 100 percent effective in regard to social regulations," says Proctor Carey, "and perhaps that's why we don't have any problems. Maybe they have problems, but as far as we can see they have things well under control, and that's fine with us. After all, it's their college."

The dormitory chairmen and their committees, in turn, regard their duties as nominal. "So far as control is concerned," says one, "everyone pretty much takes care of himself. Our only problem in that direction comes during the week in breaking up hallway handball and corridor soccer games."

Penalties adjudged by the IDC-JC for "after hours violations" are severe, usually resulting in probation. They have become more severe just in recent years, according to Dean Seymour. Ten years ago, for example, penalties were given on a "parking meter principle" where a student was fined $5 for committing the violation, and $1 for each additional hour.

Student responsibility is even more a factor in the fraternities. "Policemen are in fraternities," says Carey, "at the request of the houses themselves and are paid by them. They assist in handling admission problems, and contribute to the security of personal belongings. The house officers, and on big weekends the two couples who serve as chaperones at the request of the house, handle the rest of the problems - and there aren't many. The police officer does check to be sure there is no irresponsible drinking after hours, and once in a while there's somebody under a table who needs some help getting to bed."

Dartmouth students today are as mature and moral as any in the past, perhaps more so, and the situation is probably no different at other colleges and universities, yet it is certain that not too much time will pass before another "scandal" breaks. One explanation of the phenomenon is that " 'twas ever thus." The Special Committee on Rules took a page from College history to point this up:

"Once, at an informal gathering in Washington, the perennial subject of the depravity of the younger generation came up for discussion. Webster maintained that the only remedy for the prevalent vice and folly among boys and girls was in early religious training and parental discipline. Choate . . . pointed out that there always has been, and always will be, criticism of the younger generation by their elders, and, to prove his point he quoted a Latin passage (from the period of Trajan) . . . which, freely translated, runs, 'From their cradles they know all things, they understand all things, they have no respect for any person whatsoever, and are themselves the only examples they are disposed to follow.'"1

Plato was one who would not have been surprised at the present high standard of moral responsibility at Dartmouth. "Let us not quarrel about educational terminology," he wrote in The Laws, "so long as we agree upon the proposition that well-educated men usually turn out to be good ones."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

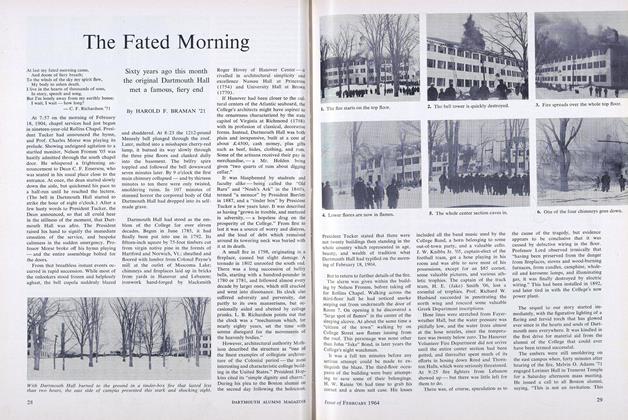

FeatureThe Fated Morning

February 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

February 1964 By R.J.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

February 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

Feature$44,180,240 and How It Grew

February 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, E. JAMES STEPHENS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1964 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

DAVE BOLDT '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1963 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63