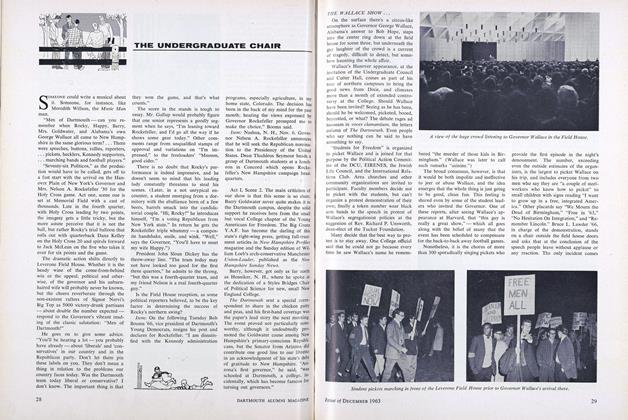

IF as Charles Schulz, creator of "Peanuts" has said, "Happiness is a warm puppy," then it might similarly be remarked by those students taking part in the New Hampshire Primary that "Politics is a cold snowstorm."

At 6 a.m. on March 10 the snow hadn't started falling above Orford as the student Rockefeller workers fanned out into the northern part of Grafton County where some polling places would open at 7 - but the storm had already spread several inches in Hanover and was sweeping northward.

Tom Phillips '64 saw the snow by television from Washington where he was the guest of Michael Goldwater, son of the Arizona Senator. Tom was resting after three months of hard work as the coordinator of Youth for Goldwater in New Hampshire.

Still a third group would play an active role in the election drama. These were more than 100 students who that night would phone in results to ABC from the polling places. The ABC representative told them they were "as vital to ABC as Howard K. Smith," and urged them to show "aggressiveness, accuracy, reliability, and determination ... those same qualities the girls from Colby Junior talk about coming home on the bus." These men would compete not for votes, but for telephone lines; not with candidates, but with NBC's League of Women Voters ladies, and CBS' town officials.

Tom and the students who spent the day passing out Rockefeller literature and driving Rockefeller voters to the polls would be partners in defeat that night, but in the morning both looked ahead to better fortune. Barry Goldwater had injected enthusiasm into his supporters two days before with his announcement that he "had it made." Paradoxically, this remark had also buoyed the spirit of the Rockefeller forces, who felt such an attitude would run against the independent grain of New Hampshire voters.

The unknown quantity was Henry Cabot Lodge. Dean Seymour, Grafton County co-chairman for Rockefeller, told this writer the night before, "We're really worried." Lou Harris, statistician for the late President Kennedy, had released a poll showing Lodge even with Rockefeller and Goldwater. Reports had come in that one town in the north of the County had bolted to Lodge, Rockefeller leadership and all.

Phillips, speaking after the election, said it had been difficult to gauge the mood of the voters while directly involved in the campaign. "We had a feeling that Lodge might beat Rockefeller, but we never thought he'd finish ahead of us as well."

Despite the decisive Lodge victory, both Phillips and the Rockefeller workers had achieved some degree of satisfaction. "We beat Rockefeller," said Tom, "and that was what we set out to do." He disagreed with the thesis that the Rockefeller and Lodge totals should be lumped as the "liberal bloc." Lodge took votes from everyone, including Nixon, he felt.

The thirty men who had been the center phalanx of the Grafton County Rockefeller forces could take pride in the fact that only within the bastion of their county had the Rockefeller forces held firm amid the general rout. The Goldwater legions had been decisively repulsed and the Lodge onslaught held off. Only Richard Nixon had been able to "turn their flank," politically speaking, and he finished ahead of Rocky by a scant 23 votes of nearly 8000 cast. Nonetheless they were able to withdraw in good order to the bar at the Hanover Inn's Tavern Room that night, to watch the ABC forces lose narrowly to a CBS computer.

Phillips' duties as youth coordinator brought him into the hard machinery of the Goldwater campaign. He organized groups at UNH, St. Anselm's, New England College, and in several communities, participated in planning of the visits to New Hampshire by Goldwater's two sons, Mike and Barry Jr., and accompanied them through the state. One of his pleasantest duties was the organizing of the "Goldwater Girls," the scarlet-sashed beauties who passed out literature at rallies. He speaks with real nostalgia of two blonde "regulars" and a brunette who came for "special occasions." A government major, Tom will get course credit for his campaign work by writing a thesis on the Primary.

Most of the student activity, however, had centered on the campaign of Nelson Rockefeller, choice of over 75 percent of the students according to a poll conducted by The Dartmouth. Many of the same group who stood in the snow on election day to get the last undecided votes into the Rockefeller column had crowded into Rockefeller Headquarters on Lebanon St. back in January to hear Bert Teague, Rockefeller's state ' campaign manager. "So far we've just been frosting the cake," Teague told them, "now we've got to get in there and do some chewing." Plans were outlined for a door-to-door canvassing effort, mailings, and coordination of Rockefeller's visits to Grafton County.

The canvassing was tough work with many unexpected pitfalls. One student campaigner waited for several minutes after ringing a doorbell in Lebanon's Ward 3, adjusting his tie and fingering the Rockefeller literature. Deciding no one was home, he had taken several steps down the walk when a youngster threw open the door and yelled, "My Mother says she'll take two cans of the spray stuff."

But the reward came when Lebanon's Town Hall was packed to hear the New York Governor face a panel of newsmen in Grafton County's own nationally- publicized answer to ."Meet The, Press."

The heavy publicity added still another aspect to the campaign experience. A reporter from The New York Times managed to ferret out the fact that the band traveling with the Rockefeller entourage (three-fifths of the Dartmouth Five) was being paid $35 each. He printed the fact high in his story. The band leader had picked up a little more political "savvy" when the same reporter sidled up to him the next week and asked, "How did you like the story in my paper?"

"What paper?" was all he replied.

One of the big advantages of working in the campaign, students said later, was the chance to meet the people of New Hampshire. "They're as well-informed as my neighbors back home," said one, "and they take their politics a lot more seriously."

The Rockefeller workers reorganized for the final two-week push. The County was divided into three sections. Senior Dave Hess took the north, Henry Clay, also a senior, was assigned the south, and sophomore Bob Booms handled the west. A student was assigned to each major town to coordinate with or appoint a town chairman, provide transportation to the polls, and make arrangements for person-to-person campaigning either through the mails or by telephone.

Where they worked they were successful, sometimes engineering three-to-one pluralities and pulling some stunning upsets in the conservative northern part of the County. They lost in the smaller communities which had not been covered.

The campaign was an excellent course in grass roots political science, but the excitement spread beyond the active participants. Dartmouth students were brought within handshaking distance of every major announced candidate, and the campus news media went wild in providing through direct broadcasts and on-the-scene reporters what may have been the most complete coverage available anywhere.

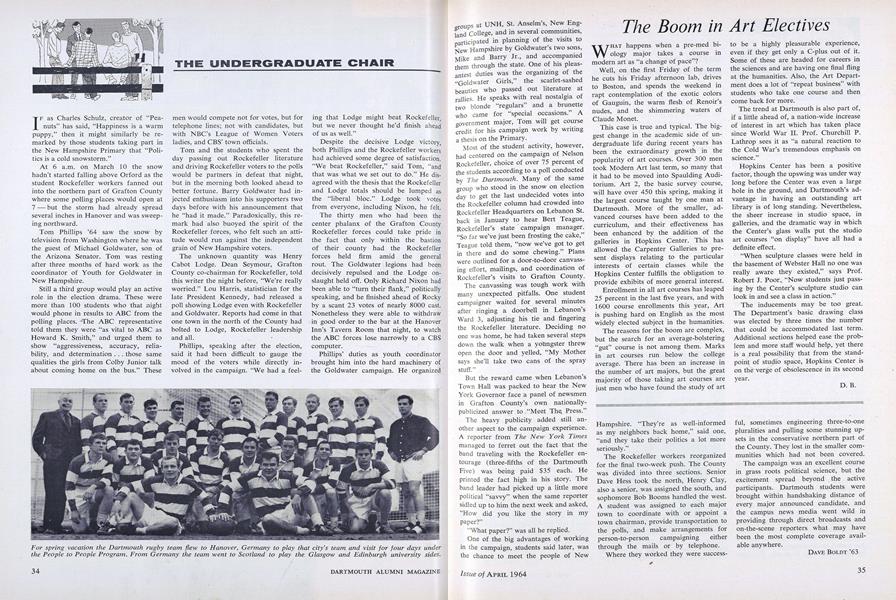

For spring vacation the Dartmouth rugby team flew to Hanover, Germany to play that city's team and visit for four days underthe People to People Program. From Germany the team went to Scotland to play the Glasgow and Edinburgh university sides.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

April 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

April 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

FeatureNew Computer Network Open to Entire College

April 1964 -

Feature

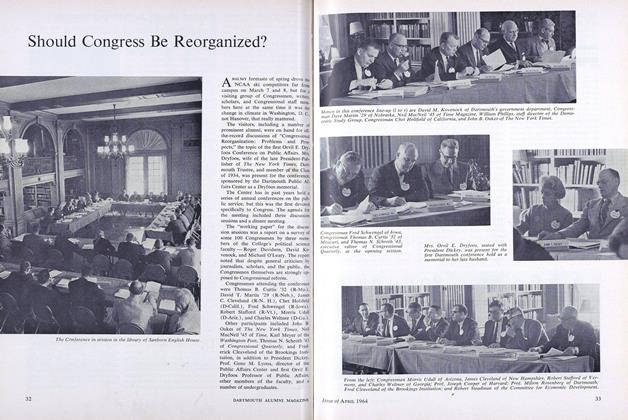

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

April 1964 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1964 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, HERMAN J. TREFETHEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

April 1964 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, PHILLIPS M. VAN HUYCK

DAVE BOLDT '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1963 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleDanube Adventure

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63