THE time dimension is distorted in the fall in Hanover. Precise days and months are blurred in the busy routine, and only football weekends remain as fixed points in the term's chronology.

Hour exams are usually pre-Harvard and post-Cornell. Fraternity rush takes place before UNH, Business Boards are Columbia, book reviews are due after Brown, term papers after Princeton. Penn is a fine time for the first date and Yale is probably the best off-weekend of the term.

This tendency to plan around nine autumn Saturdays is accentuated when the Indian football team is enjoying an undefeated season. Each week of the fall involves a familiar, yet exhilarating, sequence of events which leads inevitably and dramatically to another challenge, another showdown, another "must'' game.

Monday is reserved for armchair quarterbacks, for rehash, for basking in the glow of victory. Tuesday allows time for a look at other results, to discuss the Princeton score, to. check the national ratings, to get a date. Wednesday is game-film night, with Saturday's heroics enhanced by celluloid. Thursday is spent in a minute examination of the coming opponent - his strengths, weaknesses, weight. Thursday is also usually the last day to round up that elusive date. And, on Friday comes the rally, at 10 a.m. if the game,is away, at 7 p.m. if it is home.

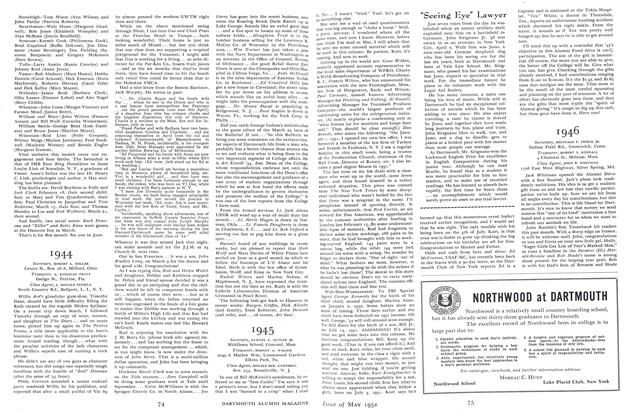

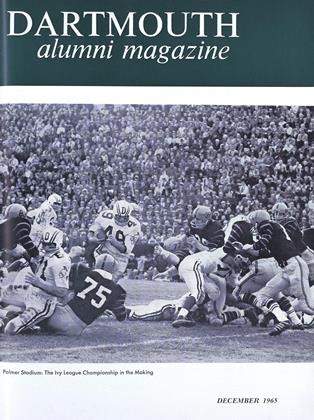

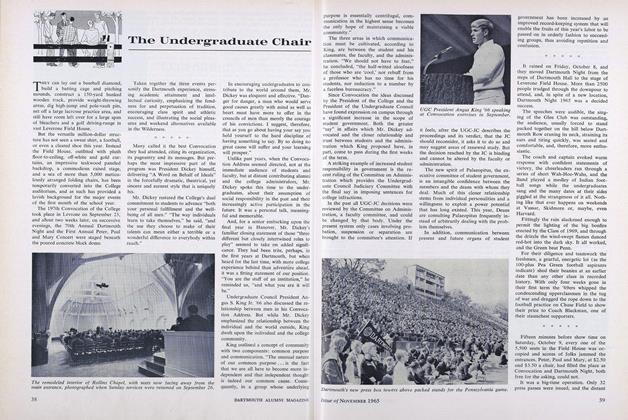

With only three home football games this fall, Houseparties took on added significance (the demand for home games far exceeds the limited supply, thus, according to Economics 1 and the DCAC box office, increasing the relative value and appeal of those few games which are available). A month had passed since Penn, a month of tough road games and increasing tension. The opponent, Cornell, was a hard-nosed, no-nonsense squad. And then there was the telecast, the live Eastern regional telecast in color, of the game.

NBC moved in early in the week building camera towers, installing instant replay units, laying cable, testing relay systems. The College cooperated by resodding parts of the gridiron, painting intricate end-zone patterns, and tinting portions of the field a deeper green.

Things went smoothly Friday. In one of the finest short-order construction jobs since Hopkins Center, the Class of 1969, starting from scratch Thursday afternoon, erected a mammoth bonfire, variously measured at anywhere from 56 to 62 ties high, which, when ignited Friday, filled the night sky with a bright red glow visible for more than ten miles around. The evening was nippy, with a touch of snow flurries, but full of promise for a fine football Saturday.

If you were one of the ten million who saw the game, you know it rained. If you were one of the 12,000 brave ones who sat in the Memorial Field stands, you know it was an exceptionally wet, unrelenting rain. But you also know that, in the best traditions of the school, the weather actually enhanced the excitement and color of the game. A whole spectrum of bright rain slickers, countless golf umbrellas, and head gear ranging from a crash helmet to folded football programs lent a certain bizarre air to the contest.

With the game telecast in Hanover, many chose to stay indoors, and fraternity "tube" rooms and the College Hall lounge were jammed with fans. But some seniors failed to catch any of the game. What with Graduate Record Exams or Law Boards in the morning followed by advanced graduate exams in the afternoon, many seniors were lucky to make the post-game champagne party let alone the game itself.

Late in the fourth quarter Indian fans initiated a "Let's Beat Princeton" chant which was a true indication of where student sentiment lay. The significance of the Tiger test, and campus anticipation, were further illustrated by the arrangement of two unique activities.

A couple of quick-thinking brothers of Sigma Nu Delta, recalling the old days at Dartmouth before regional airports and interstate highways, leased a train for the weekend and planned to run it directly between White River and Princeton Junctions, leaving Friday night and returning Sunday morning. An added attraction, besides carefree travel to Princeton, was the planned date pick-up and delivery stops at Northampton, Holyoke, and New York. With a band in the baggage car, a liberal bring-your-own policy, and an under-$20 price tag, 300 students hopped aboard.

Those who could not join the weekend commuters took solace in the fact that a rare closed-circuit television hookup was arranged. The big game was telecast live in Spaulding Auditorium and Alumni Hall of Hopkins Center. Arranged by a Boston communications company in conjunction with the Undergraduate Council, the set-up enabled more than two thousand students and townspeople to see all the action, at $2.50 and $3.50 a head.

One of the highlights of the football season, for the editors of The Dartmouth if not for the players, was the publication of a bogus edition of The HarvardCrimson on October 23 which proclaimed in 48-point Bodoni Bold that "Harvard Abolishes Intercollegiate Football."

The two-page extra, distributed to every Harvard dormitory room in the wee hours of Sunday morning after the Indians had blanked the Crimson for the second straight year, also contained articles dealing with the peculiarities of Harvard personalities, wild parties, and a special report which proved that the goldfish swallowing craze originated not in Cambridge, as is generally believed, but in Richardson Hall, Hanover. (That story only was true.)

The majority of Harvard students thoroughly enjoyed the parody, and attributed it to the Harvard Lampoon. After the source was established as TheDartmouth, many were hard-pressed to maintain their originally favorable opinion of the paper. A sizable minority did believe that the school had abandoned football, and even many Dartmouth students, who saw the issue down in Cam- bridge, returned to Hanover eager to spread the incredible story among their friends.

Later in the week, when the facts had been established, undergraduate reaction turned into a simple query: "If they can put out such a great Crimson, why can't they put out a good D?"

But the height of confusion and questioning occurred during the blackout of the entire campus on Tuesday, November 9. Students in the stacks of Baker Library, in showers at the Gym, in fourth-floor dorm rooms had to grope their way outside when at 5:36 the lights flickered and died. Men grouped together on the Green, and a widespread cheer accompanied the abrupt failure of the Main Street lights.

The College quickly channeled emergency power to busy Thayer Hall and to College Hall, but all else was dark. Candlelight dining prevailed downtown at Lou's, while nearly 50 students crowded around a transistor radio in Tanzi's listening to reports of the power blackout.

A Chemistry 51 hour exam, scheduled that evening, was called on account of darkness, and hundreds of students tried to make do with candle or fireplace il- lumination. When the lights finally came on at about 8, many men, enjoying the uniqueness of hardship, turned them off and continued to read by flame.

For one perceptive student the source of the failure was immediately diagnosed. Full of football spirit, and cognizant of the hoax at Harvard, he announced to his peers that Princeton was responsible. "They wanted to interfere with our football practice and training meal," he said, "so they pulled the plug at Niagara Falls. But we won't let them get away with it, will we?" Everyone agreed, we will not.

The Cornell-Dartmouth game on Houseparty Weekend was a rain-soaked affair.

A journalistic hoax perpetrated by the staff of The Daily Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

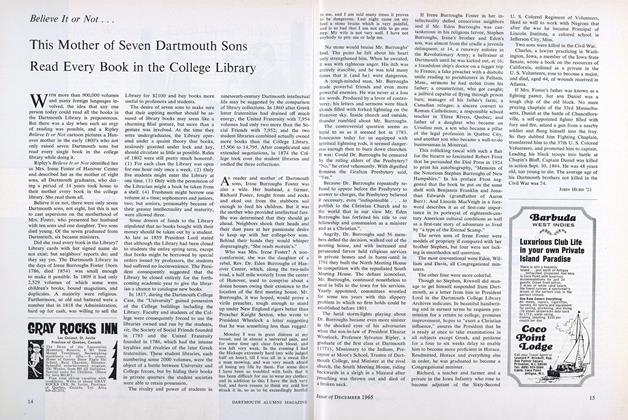

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21

LARRY GEIGER '66

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1965 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66