A RECENT article by Thomas W. Braden '40 described a game to frustrate boredom in a meeting of the California State Board of Education; the player reduces what Barzun would call the "pseudo-jargon" of a group of specialists (called "doctors of education") to simple, straightforward descriptions. For example, Mr. Braden reduced the sentence "A legitimate use of testing results for administrative evaluations must be predicated upon refined criteria to establish comparability either among schools or among groups of students to be compared" to the much clearer "Do not compare apples and oranges." The simplicity of the latter statement is enviable, though its content reveals considerable ignorance: certainly neither the original nor its reduced version says much about teaching. Yet it is from such evidence that Mr. Braden derives his case against the training of teachers.

One weakness in his argument is the tendency to equate "doctors of education" with "teachers." I doubt that an experienced teacher of, say, English would disagree with Mr. Braden in his initial analysis of the jargon. The teacher might, ill-trained though he may be, have something to say regarding Mr. Braden's subsequent conclusions and the logic on which they are based. Mr. Braden says, for instance, "As a result of playing the game I formulated a rule: in the training of teachers, education drives out knowledge." He is a good newspaper man, and he knows how to select words with impact: the cognitive leap which he takes to arrive at this conclusion, however, has the simplicity of Alexander's treatment of the Gordian knot.

It is instructive to apply Mr. Braden's method to his own prose. Consider for instance his description of a teacher: "The American school teacher is, or ought to be, the first full-time representative of the life of the mind whom our children encounter. The teacher is more than an instructor. He is a personal model from whom children derive not only their notions of the standards of an adult world, but their sense of the way their own minds should be cultivated and of the place of intellect in life."

Overlooking the possibility that parents might be considered full-time representatives, and using Mr. Braden's version of the Bishop's blade, we might reduce this to: "The teacher must be a combination of Joe Palooka and a Ph.D. in Literature." I hope Mr. Braden means Joe Palooka, and is not entirely serious about the "standards of the adult world" bit. This game of describing the perfect teacher can be played by anyone. Consider the following quote: "Schools are institutions set up by society to help the young acquire the skills, knowledge, and attitudes needed in adult living. As far as children are concerned, the main business of living in school is learning in one form or another. ... In the mental and emotional economy of youth, learning is the essential theme. . . ." This is from a textbook used in teacher education, entitled Mental Hygiene in Teaching (the title would no doubt be anathema to Mr. Braden). Is this the kind of education which drives out knowledge?

Mr. Braden's theme seems to be that there is only so much room in the mind and it ought to be crammed with subject matter: any consideration of how the subject matter is to be communicated is superfluous, even for a teacher. He uses a rather dangerous argument when he quotes the title of a doctoral thesis in education to support his view that educators are uneducated: someone might start looking up doctoral titles in Mr. Braden's former field, and asking whether a Ph.D. in Literature is entirely ready to communicate with high school students.

The main point is not found in such bickering, however, but rather in Mr. Braden's confusion over members of the community of educators. For if the "doctors of education" are high priests of the "non-subject," as Mr. Braden says, then Mr. Braden (and to some extent Mr. Conant and others in this camp) are high priests of the "non-teach." Teachers are catalysts in the learning process. Their task is to decrease the entropy of the environment, so that learning becomes more probable, and so that what is learned paves the way for more sophisticated learning in the future. Few doubt that such a role is important to our culture: many overrate our ability to perform it effectively and efficiently.

The fact is, we know very little about teaching. As a result, present debates over the training of teachers are too often between various groups of non-teachers, all of which assume mastery of a process which is unmastered. We are just beginning to explore the sociological and psychological aspects of this function, and to apply results of research in learning theory, communication theory, and social psychology to the teaching of concepts and processes in various subjects. Lest Mr. Braden be tempted to oversimplify this in translation, I am saying that what good teachers have done naturally or intuitively in the past will in the future be part of all teachers' repertoires, just as the fourth-place miler of today betters the time of yesterday's winner. This is not to say that knowledge of subject matter is unimportant; quite the contrary, it is an absolutely necessary condition for being a good teacher, but it is not sufficient. Furthermore, to say that the solution to this problem is to place the teacher in the classroom and let him learn in that context, as Mr. Conant suggests, is analogous to telling Mr. Conant that the only way to teach chemistry is to place a student in a laboratory for his entire undergraduate and graduate preparation.

Mr. Braden's analysis of educational demagoguery is worthy of a Schulman or a Parkinson. It seems that the war on "basic education" is of necessity particularly bitter under the seductive California sun. It may even be that the California-style educator poses a greater danger to the house of intellect than does his Indiana counterpart; scholars locally are taken aback by the fact that the elementary teacher in Indiana is required to have more preparation in sciences than most college degrees require of undergraduates in general. Mr. Braden still leaves a great logical and practical vacuum in assuming that more subject matter is a sufficient condition for good teaching. Furthermore, he" demonstrates an unfortunate deafness to criticism in this description of a hearing regarding revised requirements: "When I had finished, the Dean of Education Department of one of California's largest private institutions of learning rose from the back row. 'I have,' he said, 'been training teachers for 30 years. Will you mind telling me your experience in the field?' Nevertheless we went ahead. The public accepted the new regulations. The teachers did, too." An important question for the future of education in California was left unanswered, with an implicit smirk of victory over the "Establishment," subtle evidence of the basic motivation involved. The victory may have been needed, the change an overdue reaction, but as anyone who knows the complexity of teaching and our lack of knowledge of its ramifications, a forecast of troubles ahead.

And when the educators come back to the legislature, how will Mr. Braden defend his changes? Will he continue to make vague allusions to teachers who don't know their subject, or to blame the problems of juvenile delinquency on this same training? Mr. Braden himself reveals the main weakness of his argument, as he says: "Perhaps I am wrong in blaming this on doctors of education. But they have been in charge of our schools for a long time and I do not know who else can be blamed." More disquieting, however, is the hint of another basis for his concern, the confusion of liberty with equality. He says, "When our schools adopt the theory that learning is less important than some other objective ... we shall bring up a generation in which everybody is as good as anybody and nobody achieves anything at all." Using Mr. Braden's method of analysis, the last sentence can be reduced to "If everybody is treated as if he is as good as anybody else, then nobody will achieve anything at all." Having discussed advocates of "non-subject" and "non-teach," we end as he began, with non-sequitur.

Mr. Smith is Assistant Professor of Education at Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

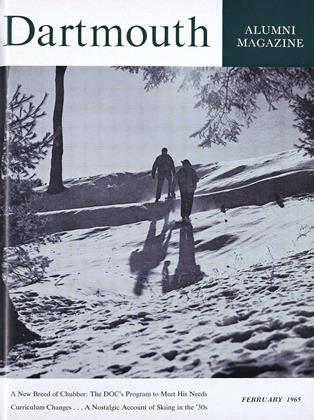

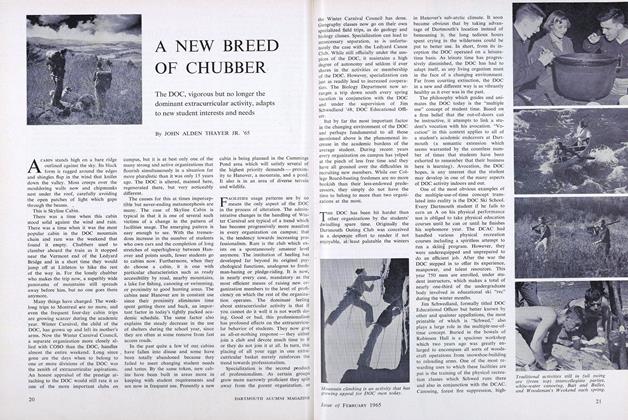

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

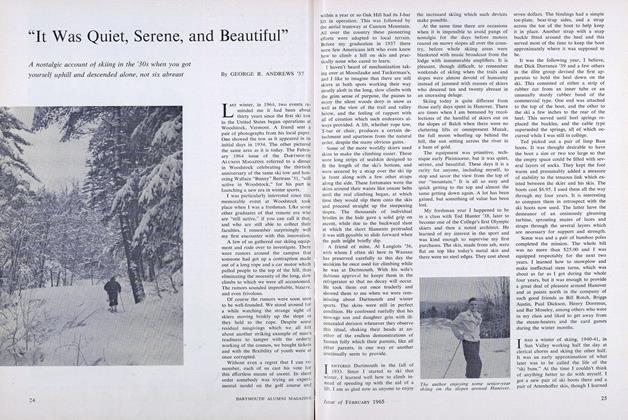

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

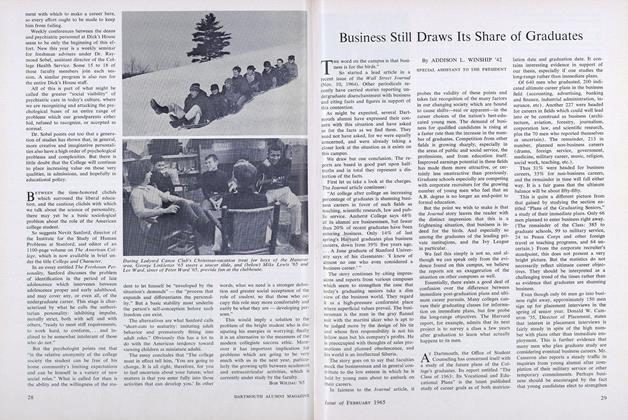

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

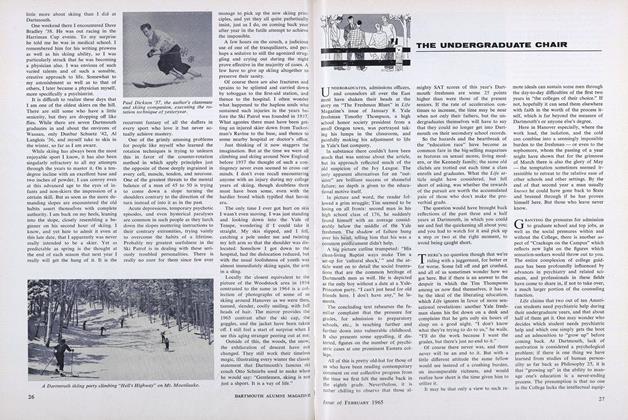

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

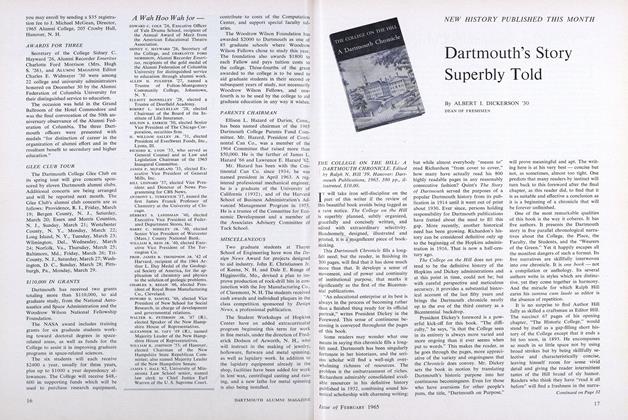

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30