THE FEDERAL BULLDOZER – A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF URBAN RENEWAL, 1949-1962.

FEBRUARY 1965 FRANK SMALLWOOD '51THE FEDERAL BULLDOZER – A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF URBAN RENEWAL, 1949-1962. FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 FEBRUARY 1965

By Martin Anderson '57. Cambridge, Mass.: The M.I.T.Press, 1964. 272 pp. $5.95.

Martin Anderson '57 has written a controversial book. Life Magazine has called The Federal Bulldozer "seriously provocative." The Journal of Housing has reviewed the same study as being "essentially a useless book." Any publication that draws such widely divergent opinions must obviously be dealing with some highly volatile material, and such is the case here.

Anderson has attempted to analyze our national urban renewal program before concluding that it is an ignominious failure that demands outright repeal. Since the Federal Government has spent well over one billion dollars on urban renewal, and since this program now encompasses actual or planned projects in nearly 800 U.S. cities, it is small wonder that Anderson's study has been surrounded by fireworks. Indeed, one would wonder whether it would be possible to occupy any middle stance between the violent pros and cons that have greeted this book.

Yet, this reviewer does feel that The Federal Bulldozer is a work that deserves both plaudits and criticism. The plaudits are warranted by the fact that Anderson has tackled a job that has long needed doing. The urban renewal effort has been with us for more than fifteen years now, and it is high time that someone should be willing to attempt a serious, objective study of this important national effort. Anderson, who is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Columbia University's Graduate School of Business, compiled the material for this book as part of his Ph.D. thesis, and whatever the limitations of his analysis, he most certainly has managed to come to grips with a subject that is of crucial significance to our national well-being.

There are limitations in the study, however, which stem primarily from the focus of Anderson's approach and the conclusions that follow from this approach. As Anderson notes quite candidly, he had no interest in the urban renewal program itself when he started his study; rather his objective was to find out more about how private enterprise would be affected by the program. Although he states that he subsequently branched out into a thorough analysis and evaluation of the entire program, The Federal Bulldozer is basically a statistical analysis (data were coded and punched on over 10,000 IBM cards which were then processed on a 1620 computer) which tends to emphasize the economic and financial aspects of urban renewal, while minimizing many of the larger social objectives of the program.

Except for often emotional references to Negroes, Puerto Ricans, and poor people "getting pushed around," the book virtually ignores the vast central city reformations that are now beginning to emerge as a result of urban renewal, nor does it really come to grips with the massive problems of racial ghettos, or planning, or the hundreds of other complex social challenges that face our cities. Rather than viewing the program as an effort to promote a cooperative attack by public and private parties on the common enemies of slums and urban blight, Anderson is inclined to view urban renewal as some sort of a conspiracy against the free enterprise system, even arguing at one point that "it attempts to bypass or short-circuit the framework of the private market."

Largely as a result of this approach, Anderson comes up with a severe indictment of the program, concluding that it is "very costly, destructive of personal liberty, and not capable of achieving the goals put forth by Congress." What would Anderson put in its place? .. The record of what has been achieved outside of the federal urban renewal program by private forces is an eloquent testimony to what can be done by a basically free-enterprise system." To buttress his argument that only free enterprise can do the job, Anderson cites Census Bureau statistics that indicate a decline in substandard housing during the past quarter century. Yet, he virtually ignores the implications of the fact that these very same statistics indicate that, as of 1960, there were still 10.9 million substandard dwelling units in the U.S.

One cannot help but contrast Anderson's book with Let In The Sun by Woody Klein '51 which was reviewed in the November issue of this MAGAZINE. Whereas Anderson tends to concentrate on statistics, Klein is concerned with the impact of slums on people. After viewing the squalor that surrounds one group of our nation's 38 million slum dwellers, Klein notes that he would reply to those critics who would slash the budgets of our federal programs for housing, welfare, or health programs that have failed to eliminate poverty or slums: "We have not found the solution to cancer either, but do we cut back on medical research and experimentation?"

In short, I cannot help but view Anderson's book with very mixed feelings. I admire the magnitude of the job he has tackled, I sympathize with the problems he has faced in securing accurate data for his study and with the efforts he has made to surmount these problems, and I feel he has performed a major service in stripping away much of the mythology that has surrounded our urban renewal effort. I cannot agree, however, that the urban renewal program, when viewed in its larger perspective, has been the disastrous failure he portrays; nor can I share his optimism that we can afford to wait for the forces of free enterprise, alone, to eliminate the urban shame that scars the face of this richest nation in the world.

Associate Professor of Government

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

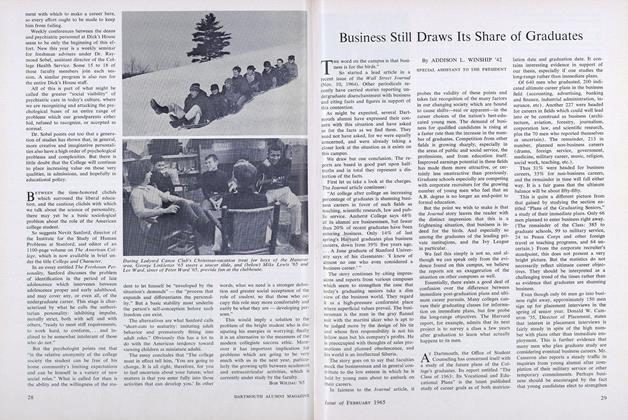

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

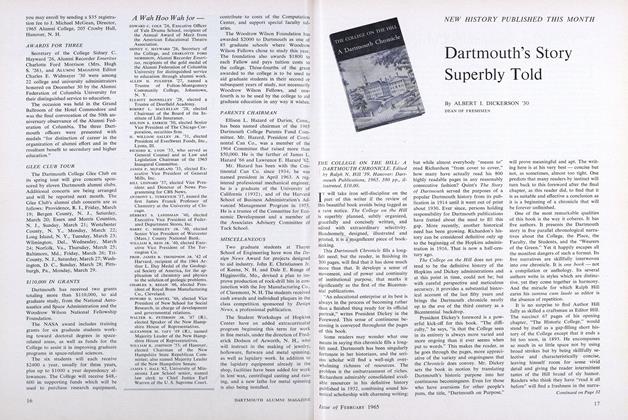

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30

FRANK SMALLWOOD '51

-

Books

BooksPOLITICAL THOUGHT IN AMERICA

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksTHE MAKING OF URBAN AMERICA

JULY 1965 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksNEIGHBORHOOD GROUPS AND URBAN RENEWAL.

JULY 1966 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksTHE ZONING GAME: MUNICIPAL PRACTICES AND POLICIES.

FEBRUARY 1967 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksThe War Won?

November 1978 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

MARCH 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Books

BooksLARKS, NIGHTINGALES, AND POETS: AN ESSAY AND AN ANTHOLOGY,

May 1938 By F. L. Childs '06 -

Books

BooksSWITZERLAND ON FIFTY DOLLARS

May 1934 By Frederic P. Lord -

Books

BooksLIFE ALONG THE CONNECTICUT RIVER.

June 1939 By Harold G. Rugg '06. -

Books

BooksHUDSON BAY EXPRESS,

January 1943 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksSCIENCE AND THE UNSEEN WORLD

APRIL 1930 By W. M. Urban