Edited by LaurencePerrine and James M. Reid '24. NewYork: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.,1966. 289 pp. $4.95.

This book contains 100 poems, each with a brief commentary by one of the two editors, Laurence Perrine, chairman of the English department at Southern Methodist, and James M. Reid '24, formerly Senior Vice-President at Harcourt, Brace & World. The commentaries are written in straightforward, layman's language, and the book is designed to introduce a reader with little experience of poetry to the important American poets of the twentieth century.

In their choice of poems, the editors have clearly striven for variety: there are long, narrative poems and short lyrics, sonnets and free verse forms, philosophical musings and light entertainments. Some of the poems, like Eliot's Waste Land, are known to all; others, like Anne Halley's Dear God,The Day Is Grey, are not well-known, but should be. While some of the poems seem to have, been chosen more for their subject matter than for their artistry, the editors are certainly to be congratulated for their intelligent selection.

The commentaries are another matter. The editors spend far too much time elaborating upon the "truths about life" which they find in the poems. They tend to state these "truths" in bald and conventional terms, to reduce the meanings of poems to platitudes and cliches: "We cannot tell from outside appearance what may be going on inside a person"; "Twelve lines compress the dilemma of modern life: how machines, both scientific and political, have increased our power at the cost of depersonalizing our relationships." Such "truths" as these are not difficult to find in poems, but, lest the reader should miss them, he is often subjected to sentimental personal appeals: "We are all vulnerable"; "Sometimes the world is too much for a person." The editors constantly try to justify poems by their subject matter. They are especially impressed by poems dealing with the great issues of the day, and will praise a poet for treating them, even if — as in Howard Nemerov's SantaClaus or Alan Ross' Radar — he does so in a crude and uninteresting way.

Much of the space devoted to discussions of theme could have been better used for technical analysis. The analysis in these commentaries is sometimes very good, but it is often too brief and general to be of much help. Mr. Perrine is generally the more successful in showing how the language of the poems works in relation to the sense. Mr. Reid tends to describe technical effects, rather than analyzing them. In his commentary on Anne Sexton's The Fortress, for example, Mr. Reid remarks: "This is a highly disciplined poem, with its rhymes and near-rhymes carefully ordered.... The rhymes are sometimes very approximate, of course; but they are there, and they follow the same pattern in each stanza."

Mr. Reid does not, however, attempt to explain how these rhymes and this stanzaform relate to what is being said. He ends this commentary, as he does many others, with a statement of high praise ("Clearly a first-class poetic talent reveals itself here."), but such statements can only ring hollow when unsupported by precise analysis. I don't at all wish to suggest that Mr. Reid does not appreciate poetic effects. He is certainly capable of technical analysis, when he chooses to use it, and his precise commentaries upon Marianne Moore are among the finest in this book.

Assistant Professor of English

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

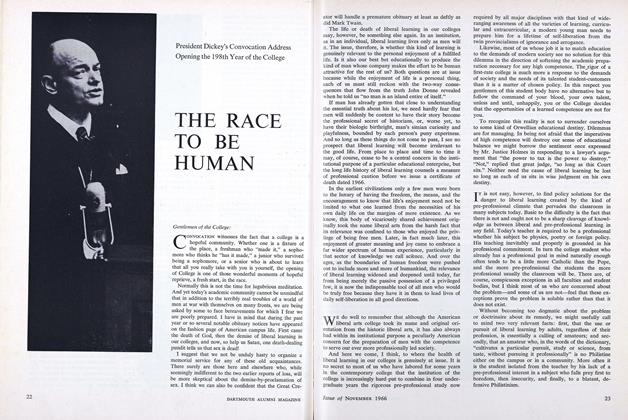

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

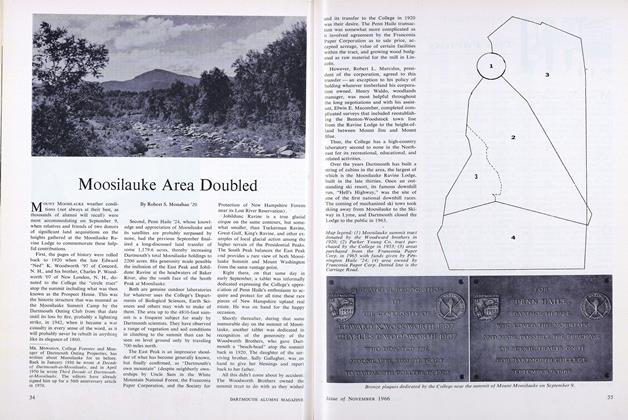

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

November, 1930 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Books

BooksPOUNDITOUT.

April 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksADVANCED ORGANIC CHEMISTRY

February 1950 By Elden B. Hartshorn '12 -

Books

BooksTHE ZONING GAME: MUNICIPAL PRACTICES AND POLICIES.

FEBRUARY 1967 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksA Giant Step Back

November 1979 By Richard. M. Watt '52