WONDERING what to do, Eleazar Wheelock walked out of the church meeting that hot summer evening in 1754. He tramped along the dusty roads of Lebanon, Conn., meditating and praying for guidance in this crisis of his long ministry.

Life in Colonial America in the middle of the 18th century was peaceful, quiet, prosperous and highly civilized. After the death of Queen Anne in 1714 England enjoyed a generation of good harvests plus a very prosperous overseas trade. This beneficent condition was fully reflected here. By mid-century there was a great religious revival both here and in England.

Wheelock, born in 1711 at Windham, Conn., was graduated from Yale in 1733, becoming at once the pastor of the Second Congregational Society in the north parish of Lebanon (now Columbia), Conn., only a few miles from his birthplace.

Dr. Benjamin Trumbull, the historian said: "He was a gentleman of a comely figure, of a mild and winning aspect, his voice smooth and harmonious, the best by far that I ever heard. He had the entire command of it. His gesture was natural, but not redundant. His preaching and addresses were close and pungent, and yet winning beyond almost all comparison." The Reverend Dr. Burroughs also reported of Wheelock: "He studied great plainness of speech and adapted his discourse to every capacity, that he might be understood by all." And this man labored lovingly in a poor hill town in eastern Connecticut.

That summer evening he was sorely perplexed because his parishioners had informed him that they could pay him but one-half of his salary. He made his decision on that evening walk; if the church could pay him but half, he was entitled to devote part of his labors to others. What should he do with his efforts? The decision came quickly. He would give half of his labor to the education of Indian youths, making them educated Christian ministers. It was Eleazax's belief that to convert the Indians to Christianity would protect the frontier better than forts and soldiers.

By December 1754 Wheelock had started his Indian Charity School in his own home with two Delaware Indian boys, John Pumpshire, 14, and Jacob Woolley, 11. As the school grew, Joshua Moor of Mansfield gave two small buildings and two acres of land for the use of the infant school.

The little school grew slowly but steadily and knowledge of it spread across the ocean to England. There was in England at that time a very considerable interest in saving the souls of the heathen savages. This interest was both institutional and individual. The London Commissioners, for the propagation of the gospel among the heathen natives of New England and the parts adjacent in America, began to help by sending Wheelock £12 in 1756, and by 1760 were sending him an annual allowance of £20, supplemented by special allowances, like the one in 1761 of £12 for the son of Isaiah Uncas, sachem of the Mohegans. That same year he received financial help from the Hon. Scotch Commissioners of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge.

Wheelock began to receive rather large donations from personages in England including the Earl of Dartmouth, then a minister of the King. These funds became large enough to lead lawyers to arrange for Wheelock to draw a will in favor of the school and also to appoint trustees in England to hold the money collected there.

By this time Moor's Indian Charity School had 25 students, and Wheelock had proven himself not only an eminent teacher and divine but also an excellent businessman. He had a long-time friend in England, the Rev. George Whitefield, who wrote him in 1760, "Had I a converted Indian scholar that could preach and pray in English something might be done to purpose."

Late in 1765 Wheelock sent Samson Occom (Indian) and Nathaniel Whitaker (a Connecticut clergyman) to England to preach and raise money for the school. George Whitefield introduced them to "the truly noble Lord Dartmouth" and to his Majesty. They passed from town to town and city to city throughout England and Scotland. Occom was an inspiring preacher. Over £10,000 was raised and deposited with the trustees in England. While some of the money was raised by passing the plate, most of it came from individuals whose names are preserved to this day in the records at Hanover.

With money the school could grow and it was apparent that the facilities at Lebanon were inadequate for expansion. Wheelock began to look elsewhere. Two requirements had to be met: (1) a large tract of land for the better support of the school, and (2) a location near the larger Indian tribes on the frontier. Word of the move spread and there was considerable competition to secure the new home of the school.

Governor Wentworth of New Hampshire was most eager to have Wheelock locate in the western part of his province in the belief that it would draw more settlers to that wilderness of virgin forests. Wheelock sent the Rev. Ebenezer Cleveland as his chief emissary to look the land over. The report was favorable and the idea met with approval among the trustees in England. The choice was the Hanover plain, above the Connecticut River, many long miles from civilization by ox cart over almost non-existent roads. Giant trees covered the soil. The eighth decade of the century was approaching and Wheelock was 58 years old.

As the plans evolved it was decided to include with the Indian Charity School a college for English students. These English youths were to be trained for the ministry, more particularly for missionary work with the Indians.

Contrary to legend, Wheelock took the liberty of naming the college Dartmouth College. He did this without waiting for Lord Dartmouth's consent because of the slow mails and because, as he expressed it, nobody knew what was going to happen "in the present ruffled and distempered state of the kingdom" (1769 shadows of the Revolution to come). On December 13, 1769 the Charter of Dartmouth College was issued and the purpose is set forth as the "education and instruction of the Indian tribes - for civilizing and Christianizing the children of pagans - and also of English youths, and any others." Only in March of 1770 did Wheelock write to Lord Dartmouth that the college had been named for him.

The summer of 1770 found Eleazar Wheelock writing to his friend, George Whitefield, "From my Hutt in Hanover Woods in the Province of New Hampshire." This was a small log house about 18 feet square, his headquarters while from thirty to fifty men labored to build him a one-story house, 40 by 32 feet, and a college building of 80 by 32, two stories high. There were trees to be felled so that crops could be planted the following year. Hanover was remote from civilization in those days though the area had been opened up by the crude military road which was built from southern New Hampshire to Crown Point on Lake Champlain during the French and Indian War. The nearest neighbors were two and a half miles away.

The college opened for instruction in December of 1770. Food had to be shipped in with great difficulty, so much so that part of the students had to be sent back to Connecticut. Wheelock was a distinguished classical scholar and his assistant, Bezaleel Woodward, was extremely able in mathematics and science. The infant college graduated its first class in 1771, three of the members having completed their first three years at Yale and the fourth appears to have been tutored privately.

At the end of the first college year Wheelock was already sixty years old and carrying a heavy load of teaching and administration. The students numbered about thirty. Besides the first two buildings Wheelock built a saw mill, a grist mill, two barns, and various small buildings. Many acres were cleared and planted for hay, corn, and wheat in order to produce bread for the school and fodder for the farm animals.

The college students grew in number, perhaps even faster than the produce of the land. Hundreds of acres were cleared of the huge trees. Thirty to forty men labored at the school. By the third year the student body had risen to about eighty. Eleven comfortable "dwellinghouses" were erected by new settlers near the college.

Expenses were burdensome, not only because of development costs but also because the college had to support "sixteen or seventeen Indian boys - and as many English youth on charity - and the expenses for three and sometimes four tutors" (we could call them instractors). Growth continued, not only in numbers but also in problems.

The onset of the Revolution was a severe blow to Dartmouth College because it cut off financial support from England. In fact money already raised was held back by the war and not recovered until some years after Wheelock's death, which came on April 24, 1779, when he was 68 years old. The college was by then well on its way to success.

There is a lesson to be learned from this story. It is the ability to snatch victory from defeat. Eleazar Wheelock could have tightened his belt and scraped along on half pay until times might have gotten better. But no, he went out and found a second task to be done and it carried him to unsuspected heights.

Eleazar Wheelock

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

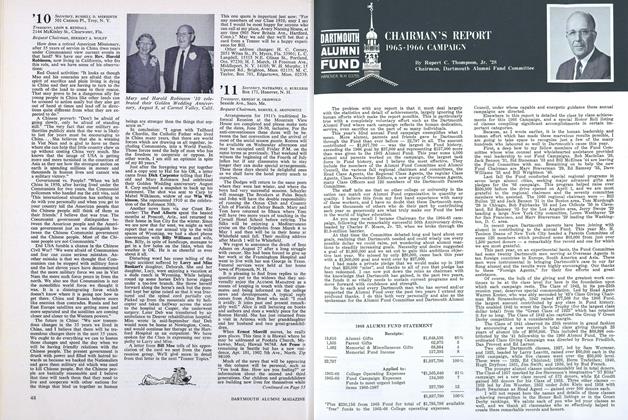

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

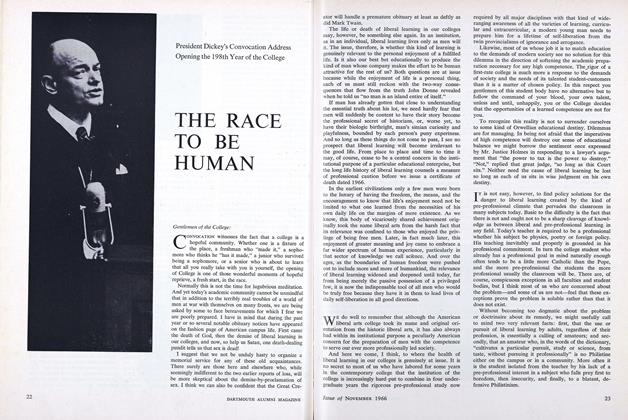

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

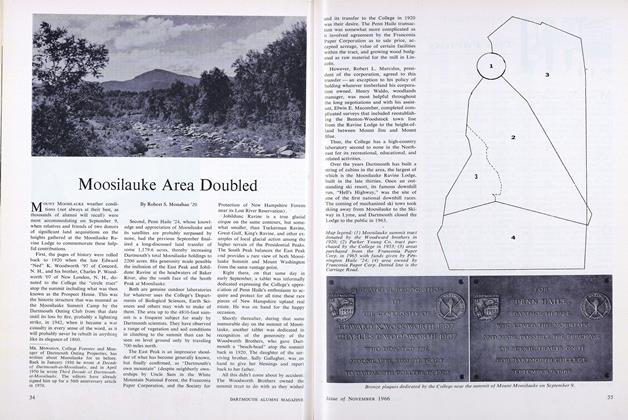

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

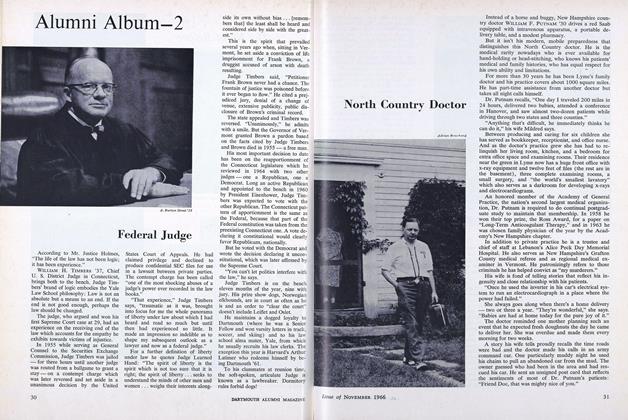

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966

Cleveland Poole '24

Article

-

Article

ArticleA Gift Suggestion

DECEMBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleGIFTS, GRANTS & BEQUESTS

DECEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleMedical Humanism

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleTHE SPIRIT OF '21

December 1941 By George L. Frost -

Article

ArticleDogs

FEBRUARY 1932 By W. H. Ferry '32 -

Article

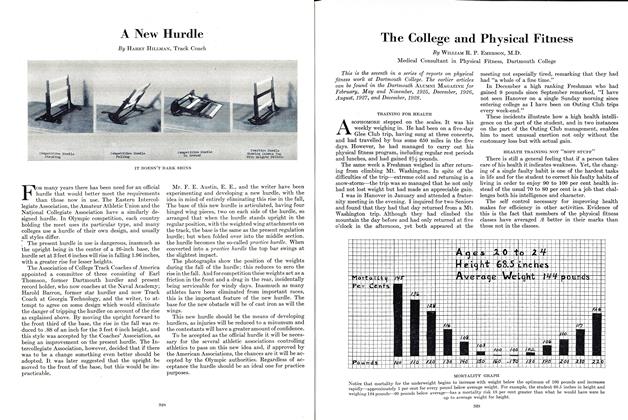

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

MARCH 1931 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D.