The experience of a new president is similar to that of the young second lieutenant who takes command of a company with a veteran corps of non-coms. While the non-coms carefully humor the new officer, they feel it their sacred duty to carry on the business of the company as they always have - no matter what the new lieutenant says.

The President of the United States has a much easier time. Although he must continue to work with the corps of civil servants, he has a free hand in choosing his own cabinet. My charge from the Board of Trustees was that I would have a completely free hand after one year in office. I was asked not to remove any of the senior officers for the first 12 months, to provide continuity in the administration. In retrospect I think that this was a mistake. I strongly recommend that the next President of Dartmouth be helped by a Trustee requirement that senior officers submit their resignations. It will make it much easier for him to make a few changes, and even if he keeps the same senior officers, they will become "his people."

It would have been easy, in a way, if I had found a large number of incompetent people in the ranks of the administration. But clearly Dartmouth could not have prospered, as it did, with that level of incompetence. The problem comes with first-rate officers who disagree with the policies of the new President; and frequently it is not even a question of new policies, but a question of style. I happen to be a strong believer in an open style in which a maximum of information is shared with all those who are concerned. This is contrary to the custom of most American colleges, and I had serious difficulties getting my point of view accepted.

It is in the nature of bureaucracies to try to protect pockets of information. Exclusive right to information gives administrators special power and protects them in case serious mistakes are made. I happen to favor sharing all kinds of information with faculty, students, and alumni. But even short of such a radical move, I felt it was essential that the chief executive officer of the College - the President - should have access to all information. It was a struggle before I achieved that goal!

A president chosen from within has temporary advantages over an outsider in that he already knows a great deal about the institution which he will lead. But in a college as complex as Dartmouth, even a faculty member of 16 years standing, who had been active in many College activities, found that there were vast areas of which he was totally ignorant. I was therefore extremely grateful when an alumnus offered a gift to retain a consulting firm to conduct an intensive study of the non-academic administration of Dartmouth. A team from the firm of Cresap, McCormick and Paget performed a major service for the new President in helping him understand the strengths and weaknesses of the administrative organization. Their recommendations led to significant changes, even if the measures eventually adopted were different in many cases from the specific proposals. Most important, the consultants made it possible for me to learn the intricacies of the administration much more quickly than I could have done on my own.

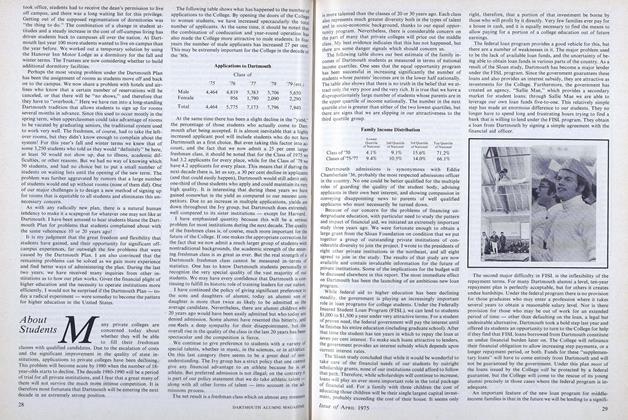

In the resulting reorganization greatest attention was attracted on campus by changes in the vice-presidential-level administrators. Since this reorganization led to some wildly exaggerated stories (a typical joke: "May a mere dean sit at this table? '), I should like to separate fact from fiction.

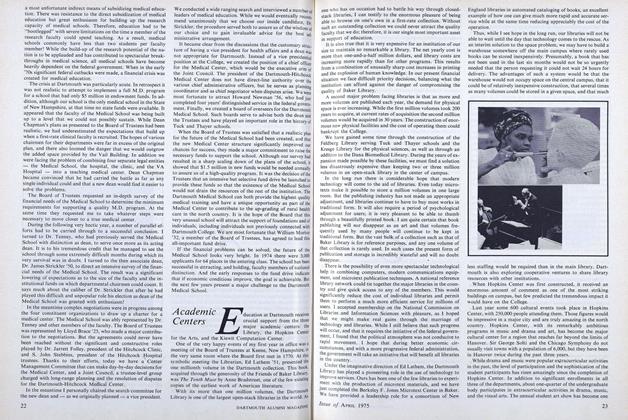

Let us examine the list of senior officers whose appointment and salaries the Board of Trustees has to approve. The following chart shows the list when I took office and the way it is now.

Lei. me first comment on the two positions "below the line." he position of vice president for women's affairs, filled so ably by Ruth Adams, was conceived as a transitional position to help us in implementing coeducation. It was our agreement that Ruth would serve full-time for three years, part-time for two years, and then we would discontinue her office. The position of vice president and chairman of the Investment Committee, held by John Meek '33, is a transitional position on a part-time basis. After John's retirement in 1977, the College will have to appoint an investment officer, but not at the vice presidential level. Therefore, the net long-range increase in senior line officers has been exactlyone.

Senior Line Officers1969 1975 President President Provost Dean of Faculty Vice President & Dean of the Faculty Vice President & Dean for Student Affairs Dean of Medicine Dean of Medicine Dean of Tuck Dean of Tuck Dean of Thayer Dean of Thayer Vice President-Treas. Treasurer Vice President for Administration Vice President Vice President for for Development Development Vice President & Chairman of Investment Comm. — Part-time until 1977 Vice President (Women's Affairs) — Part-time until 1977

As can be seen from the chart, the major reorganization occurred in two areas. The positions of provost and dean of the faculty were replaced by two vice presidential positions with quite different job descriptions. And the position of vice president and treasurer has been split into two positions, that of treasurer and that of vice president for administration.

The title of provost (or academic vice president) is used by major universities that need a chief officer to coordinate the work of the deans of many separate schools. Dartmouth has only the College of Arts and Sciences and three relatively small professional schools. I suspect that the position of provost was created in the late 1950s when the problems of the Medical School demanded a great deal of attention. However, when Carleton Chapman was appointed dean of the Medical School, one of the conditions for his coming was that he report directly to the President of the College. This removed one of the main reasons for having a provost. By 1970 the provost's job was somewhat of a hodge-podge. He supervised the deans of Arts and Sciences, Tuck, and Thayer; the dean of graduate studies (for our small Ph.D. programs); such institution-wide facilities as Hopkins Center, Kiewit, and the Libraries; and a wide variety of officers dealing with student affairs. The incumbent was Leonard Rieser, one of the most highly respected academic officers in the United States. A past chairman of the Physics Department, he has recently completed a term as president and then chairman of the board of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

While I had no doubt that I wished to retain the services of Leonard Rieser, there was something drastically wrong with the administrative arrangement. Promoted to the position of provost from the rank of dean of the faculty, he retained a primary interest in the welfare of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. This put us into the anomalous position that the decisions of the dean of the faculty could be second-guessed by the provost, and, with a President who himself had been a long-time member of this faculty, the decision might be third-guessed by the President. At the same time, I was concerned about the wide array of student services that were receiving insufficient supervision, simply because no one person could carry all the duties assigned to the provost.

After some trial and a few errors we arrived at a new academic administrative structure that seems to be working well. Leonard Rieser as vice president and dean of the faculty is the officer who acts for the President in his absence. He has jurisdiction over all faculty members (except for the Medical School which still reports to the President), including graduate studies and continuing education.

A new position of vice president and dean for student affairs was created and filled from the ranks of the faculty. First to hold this office was Donald Kreider, a member of the Dartmouth faculty for more than a decade and one of the most able and popular teachers at the College. His primary responsibility has been the supervision of a large number of extremely important offices dealing with students. These include the offices of the dean of the College, the dean of freshmen, financial aid, counseling, outdoor affairs, the Tucker Foundation, and the health service. He was given the very difficult challenge of consolidating and reducing in size a dozen different offices, which he has met admirably. In addition the major institutional centers were divided, somewhat ar- bitrarily, between vice presidents Rieser and Kreider.

The realignment of these two key positions has led to clear-cut line responsibilities and has eliminated overlapping jurisdictions. Above all, I have developed excellent working relations with both officers. It was therefore with great regret that I received the decision of Don Kreider to return to full-time teaching. He will be succeeded next year by Professor Franklin Smallwood '51.

The problem confronting me in the non-academic administra- tion was quite different. John Meek, who has a great national reputation as a financial officer, held down a set of respon- sibilities that no two people could possibly discharge. This was due in part to Dartmouth's vast growth in complexity during the Dickey administration and in part to the many talents combined in one individual. He had direct or indirect responsibility for all fiscal and business matters of the College, personnel policies, record-keeping, investment policies, and legal affairs. My solution was to split the job in two. Rodney Morgan '44, vice president for administration, now has responsibility for all the farflung business activities of the College as well as personnel policy. William Davis, treasurer, is the chief fiscal officer at Dartmouth with responsibility for budgets and financial record-keeping. Until his retirement, John Meek will maintain chief responsibility for investments and legal affairs. Again, I believe that we have much clearer lines of responsibility and therefore much tighter control on these non-academic aspects of the College.

Although the number of positions has not changed significantly, there has been a realignment of responsibilities and a large turnover in personnel. Of the 11 current positions listed in the chart above only 4 are now filled by individuals who had such senior responsibility in 1969: vice presidents Colton, Meek and Rieser, and Dean Hennessey. Four of the remaining positions were filled by promotion from the ranks of the faculty. In addition to myself, these are Vice President Kreider and deans Strickler and Long. Mr. Davis was promoted from within the ranks of the administration, Mr. Morgan was recruited from industry, and Ruth Adams was attracted to Dartmouth after she stepped down as president of Wellesley College.

While I am satisfied with the size and quality of the senior administration, I have distinctly uncomfortable feelings about the total size of the administration. This issue came to a head last spring when, under the pressures of unfavorable financial developments, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences severely criticized the size of the administration.

In order to understand the following facts, I should explain that employees of the College are classified into one of four categories: faculty, administrative officer, staff, or service employee. The first two categories are referred to as "officers," and roughly speaking an officer is one who either has line responsibility or serves to represent the institution. All officers other than those whose primary assignment is teaching are classified as "administrative officers." One tends to think of administrative officers as vice presidents and deans, but the vast majority of them have quite different responsibilities. For example, professional librarians at all levels are administrative officers, as are coaches and all those members of the admissions office who do interviewing. (Thus we have the anomaly that a high-paid computer programmer or laboratory assistant is a staff member, but a junior assistant to the director of admissions or to the dean of the College is an officer.) In preparing my response to the faculty, I discovered astounding figures about the growth of the administration at Dartmouth.

When President Tucker took office in 1893, he was the only administrative officer in the College, but by the end of his term the total had grown to ten. Fifty years ago the number was roughly 30, and by 1940 it had grown to 42. In the period 1940-1968 it grew to 201, an astounding growth rate of 9.1 per cent per year! With vast changes since 1968 the number has climbed to 267.

I understand the growth from 1968 to 1974. The combined effects of a large expansion in the student body, the equal opportunity program, affirmative action, coeducation, and year-round operation can justify most of the increase in the administration in the past six years. It can justify most, but not all of it, and in the present budget-cutting exercise we will cut back in those areas where we have over-staffed.

However, I have the greatest difficulty in understanding the vast increase from 1940 to 1968. I have made some rough comparisons and find that the size of our administration is not out of line with those of institutions of comparable complexity; therefore, this must be a national trend. I can identify at least some of the forces that led to the spectacular increase during a period when there was very little increase in the size of the student body. I suspect that in 1940 faculty routinely carried out many responsibilities that are now assumed by professional administrators. The College has also engaged in many new activities, such as Hopkins Center and the computation center, which have required the addition of a significant professional corps. The Library has grown vastly both in size and in sophistication. (Fifty years ago there were only two officers in the Library and most of the books in Wilson Hall were inaccessible.) Admissions and financial aid were once very simple operations; they now require a large professional staff. The coaching of athletic teams was once carried out primarily by part-time volunteers and now requires a corps of professionals. Federal regulations have added enormously to the demands of record-keeping as have the requirements of a modern development program. There has also been a sizeable increase in the various auxiliary activities of the College.

While I understand these explanations, I share the faculty's uncomfortable feeling that the administration is too large. Other than the cuts we will be able to make this year, I cannot identify areas where we are overstaffed. But I do have a feeling that we may be overextended, that we are trying to do too many things which - no matter how worthwhile - are not essential to the centra! purpose of the College.

One of the important contributions of the organizational study conducted by Cresap, McCormick and Paget was the identification of a serious problem in our salary and promotion policy. While for the faculty the rules are strict and clear and in the service area are determined through union negotiations, we did not have any clear policies for administrative officers and staff. Salaries for new positions were determined individually by each supervisor through negotiation. Once a person was hired, annual raises depended only in small part on merit. As a result, salaries depended more on the seniority of the incumbent than on what the job was worth or how good the employee's performance had been. We had no system for comparing the importance of various jobs and no clear-cut concept of promotion within either the staff or the ranks of administrative officers, other than giving a salary increase.

One of the significant achievements of Rod Morgan was to design, with the help of the consultants, a complete system of grades and salary schedules for administrative officers and one for staff employees. For example, for administrative officers we have eight grades below the vice presidential level, and all existing jobs have been classified into one of these grades. For each grade there is a minimum and maximum salary. The salary of a new officer how depends on the grade assigned to the job and on the experience of the officer. Raises within the grade are given partly on the basis of seniority but also on the basis of merit. Once an officer reaches the maximum for the grade level (a maximum which is adjusted periodically due to inflation) only cost- of-living increases are allowed.

This system has already proved to have vast advantages. First of all, we can clearly inform a candidate what the possible salary range is for a given job. Secondly, it will no longer be possible for officers who remain in a given position for a very long period of time to command unreasonably high salaries. Thirdly, we have opened clear-cut opportunities for promotion for administrative officers. When a position opens up, a job description with a grade level is circulated on campus. Any officer holding a lower grade position who feels qualified for this opening may apply.

Similar procedures apply to the system of grades for staff employees. I should like to illustrate the advantages of this system through an experience in my own office. Within the first year of the new grading system we lost two excellent secretaries. Ac had applied for a secretarial position with a more demanding job description and a higher grade classification. I could not justify up-grading those two positions in my own office, and while I was personally sorry to lose them, I was very happy to see the system working exactly as it was intended to work. Without a clear-cut system of grades, it would have been inconceivable for other offices to "steal one of the President's secretaries" by offeringher more money.

To administer this new system of grades and promotions, as well as continually to monitor policies governing administrative officers, I created a committee on administration consisting of senior line officers and chaired by Vice President Morgan. This committee has significantly strengthened our whole personnel administration and has improved many policies. Periodically, they review our various fringe benefits and have been instrumental in improving these for all four categories of employees. For example, I am extremely pleased with the improved pension plan we now provide to staff and service employees. The committee is currently at work on additional improvements, including a system of periodic reviews for administrative officers and a plan for occasional sabbaticals for these officers.

Many academic institutions have struggled to develop an early retirement plan for faculty and administrators. With the loyalty of the officers of the College, it is not uncommon to have 30 to 40 years' service before mandatory retirement at age 65. The opportunity to retire a few years earlier, to take a less demanding responsibility for the last few years, or to try a second career is attractive to many individuals. Unfortunately, without a special plan the financial penalty can be prohibitive. For example, an employee who elects to retire voluntarily at age 62 suffers all of the following setbacks: Social Security payments will be significantly reduced, there are three fewer years of contributions to the retirement plan, previous contributions to the retirement plan gather three fewer years of interest, and pay-outs under the retirement plan must take three extra years of life expectancy into account. The combination of these factors will reduce retirement payments by about 25 per cent for the rest of the officer's life, a very severe penalty for reducing total service by three years. On the other hand, the usual plan that tries to make up for lost retirement income is extremely costly to the institution.

I believe that Dartmouth has devised the most equitable and ingenious plan now in existence. Our flexible retirement options allow an officer to elect the new plan at either age 60 or 62. However, he does not retire at that point. For example, an officer who elects the plan at age 60 agrees to accept a reduced salary (depending on length of service) for the next five years, but still owes the College the equivalent of two years' teaching or administrative responsibility. This may either be carried out as two years of full-time service or part-time over a larger number of years. In the meantime the College continues full contributions to his retirement plan so that he does not lose retirement benefits. The variety of options has proved very attractive. And the fact that the officer agrees to reduced salary before he completely disengages from the institution keeps the cost of the plan within reasonable bounds.

Many colleges have been plagued by serious labor problems in recent years. During my five years as President, we have three times negotiated two-year contracts with our service employees' union. The fact that in each case we were able to negotiate a reasonable compromise between the demands of the union and what the College could afford has avoided some of the bitter feelings that have arisen on other campuses. The fact that management, without pressure, took the initiative to raise minimum salaries and to improve many fringe benefit plans may have contributed to our success in the negotiations.

I should like to conclude this section by describing the development of our new management information system. Personnel record-keeping and long-range planning tools are two areas in which colleges have lagged far behind industry. I found this a great handicap when we had to impose much tighter budget control on the institution. It also created enormous difficulties in meeting new government reporting requirements on affirmative action and other regulations. With many separate sets of personnel and fiscal records, no two of them in the same form, and none of them machine-readable, just counting the total number of employees of the College was a Herculean task. Yet I was convinced that given the sophistication of the Dartmouth Time Sharing System, we could develop a relatively inexpensive and efficient modern management information and planning system.

We launched Project FIND (Forecasting Institutional Needs for Dartmouth) with the help of an anonymous Dartmouth benefactor. This seed money was later supplemented by several foundation grants enabling us to complete a task which proved more difficult than we originally envisioned. Today we are able to keep large data bases in the memory of our computer and can gain access to them from any terminal on campus in a simple language requiring no knowledge of computer programming. If I wish to find out how many full professors in English earn more than $20,000 a year, or wish to know the percentage of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences that has its undergraduate degree from Dartmouth, I can find out in a few minutes on the terminal in my office. The complicated reporting requirements of the affirmative action officer take much longer, but his task is now a manageable one. Two years ago it was almost humanly impossible. It is worth recalling that one major university lost vast sums of federal money not because it was in clear violation of affirmative firmativeaction rules, but because it was unable to provide the information required by the government!

Similar remarks apply to our entire budgeting process, to our control of physical facilities, and to keeping track of the art collection of the College. One of the nice features of the system is that most information is easily available and at the same time confidential data (such as salaries) is completely protected. We are slowly beginning to use this powerful tool to build models for long-range planning. We still have a great deal to learn, but I am convinced that in the long run FIND will prove to be one of the most important management tools for colleges and universities.

Features

-

Feature

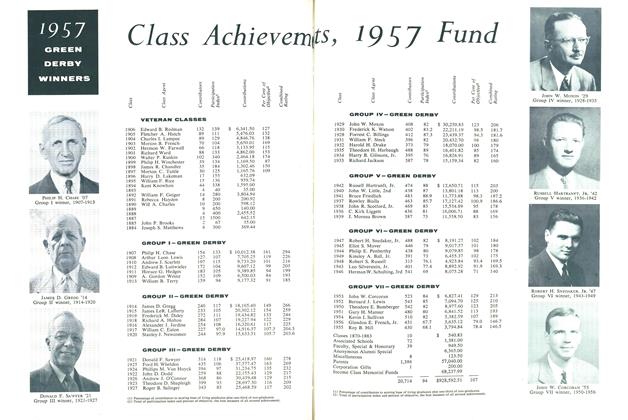

FeatureClass Achievemts, 1957 Fund

December 1957 -

Feature

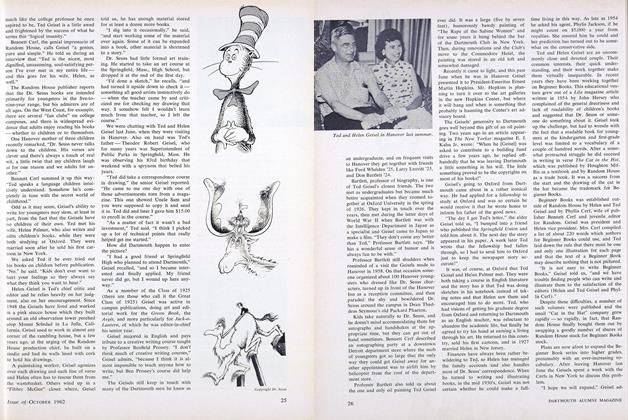

FeatureDr. Seuss

OCTOBER 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

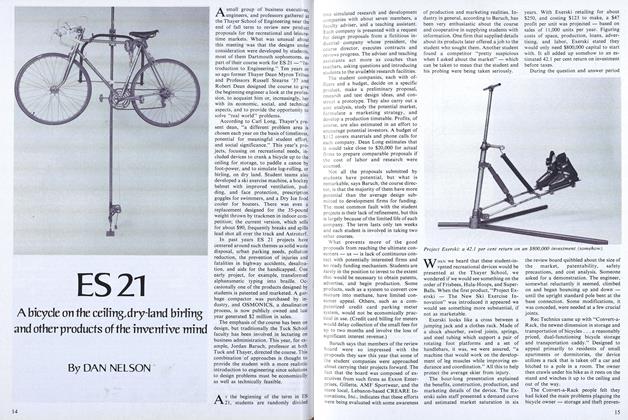

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

FEATURE

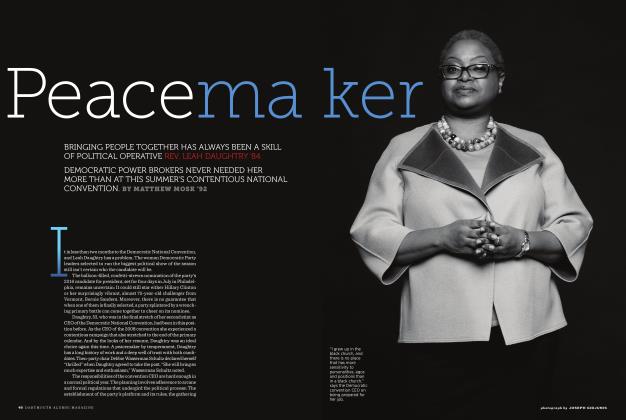

FEATUREPeacemaker

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

APRIL 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Cover Story

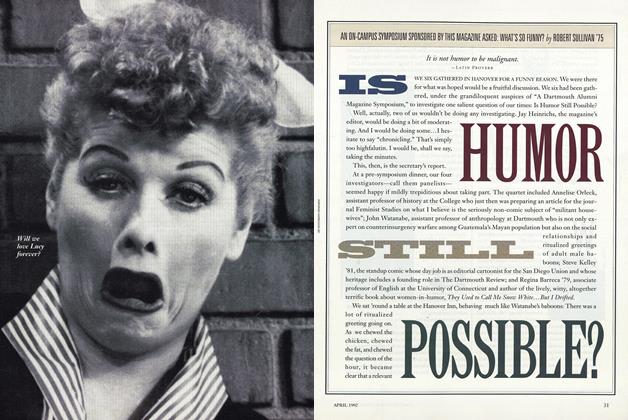

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75