By Prof. Charles T. Wood (History).Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UniversityPress, 1966. 164 pp. $5.50.

In this latest addition to the Harvard Historical Monographs Prof. Charles Wood makes a significant contribution to our knowledge of Medieval French institutions. Beginning with the Capetian Louis VIII (1223-1226), French kings provided for their younger sons by grants of extensive lands known as apanages. In legal form such grants were fiefs, and the holders owed the king the customary feudal services and payments. Modern historians have severely criticized this practice. They argue that it produced a new feudal aristocracy which retarded the unification of the monarchy. This verdict, however, has been rendered in the absence of any modern critical and detailed study of the relations of the apanages with the crown. This is a need that Professor Wood's monograph supplies for the period, 1224-1328.

The author organizes his material topically and presents it precisely and clearly. Obviously he has done a conscientious and thorough piece of research. Its most impressive feature is the extensive utilization of unpublished records of the apanaged princes preserved in the Archives Nationales at Paris and Archives du Pas-de-Calais at Arras. Specialists may wish that his notes had quoted more extensively from these sources, as the validity of his argument frequently turns on the interpretation of their wording. The general reader, however, will not regret the absence of such extensive documentation.

Professor Wood's rescarches lead him to ones. He does not find that the apanages seriously retarded the consolidation of the monarchy. Royal grants of land were effectively guarded by provisions, written or implied, for reversion to the king in default of direct heirs to the apanaged prince. More often than not these princes were agents for the diffusion of royal influence. Although legislation for the royal domain did not apply to apanages, the holders frequently duplicated it in their own legislation. There was a constant interchange of administrative personnel between the king and the apanaged. Behind the feudal facade family solidarity and dynastic advantage acted as a genuine integrating force. The apanages Professor Wood concludes (pp. 150-151)' were a basically nonfeudal institution that was clothed in feudal forms only because they were customary and proper at the time apanages were first granted."

Professor of History, Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lifelong Association of Thayer and Ticknor

June 1966 By COLONEL ROBERT S. DAY, USA -

Feature

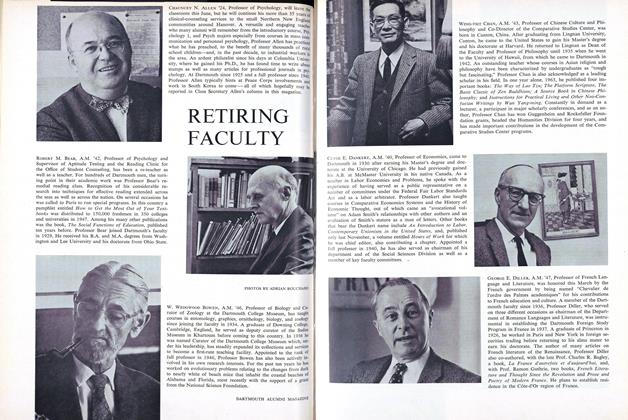

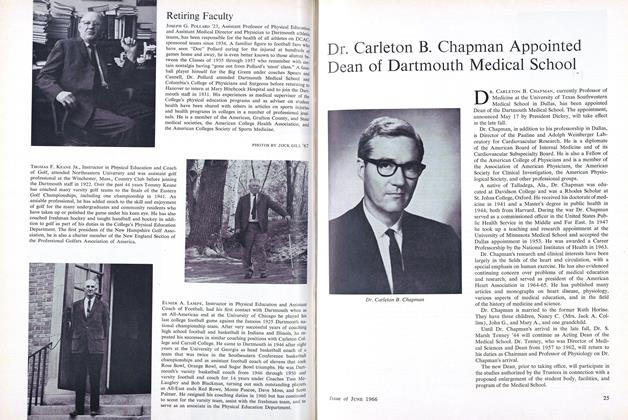

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1966 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

June 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

June 1966 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

June 1966 By PETE GOLENBOCK '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1966 By JILDO CAPPIO, ALBERT C. BONCUTTER

JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

December 1953 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

October 1954 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

December 1954 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

June 1955 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

October 1955 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1886

February 1956 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS '19

Books

-

Books

BooksPrinciples of Preaching

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksVirgin Dip

June 1976 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksA BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE WORKS OF EUGENE O'NEILL.

NOVEMBER 1931 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksTIME OF PEACE

December 1942 By H. M. Dangan -

Books

BooksUNDERSTANDING YOURSELF; THE MENTAL HYGIENE OF PERSONALITY,

January 1942 By R. P. Holben. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R.