By Fred Berthold Jr.'45. New York: Harper, 1959. 158 pp. $3.00.

In The Fear of God Fred Berthold Jr., Dean of the Tucker Foundation, treats in a thoughtful and scholarly way an important problem in contemporary thought: the significance of anxiety for understanding the human situation.

Professor Berthold's knowledge of the extensive literature pertaining to the many aspects of the problem of anxiety forms a sound background for his carefully delimited inquiry into the meaning of religious anxiety within the context of theology. "This means that the reality of God is assumed. The question for debate, on the basis of certain kinds of religious experience (anxiety), is not 'ls there a God?' but 'What concept of the relation of God and man is consistent with the experience we have?' " From this perspective, The Fear of God offers a lucid and penetrating analysis and an important contribution to constructive theological thought.

Professor Berthold's initial thesis is that, from a descriptive point of view, religious anxiety is "rooted in a positive love or desire. Far from bespeaking man's alienation from God, it signifies, even in its blackest moments, an underlying yearning for God."

He proceeds to establish this central point through a comparative analysis of the life and works of Teresa of Avila, a Catholic mystic, and Martin Luther, the great Protestant reformer, who was both doctrinally and personally far removed from Teresa. Both Teresa and Luther in their direct acquaintance with religious anxiety, the author concludes, although aware of the horror of separation from God, were "finally forced to understand it as something which presupposes man's positive relation to God."

In reading these chapters, one is struck not only with the conciseness and simplicity of the writing, but even more with a deeply sympathetic understanding of the materials at hand.

Through a discussion of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic interpretation of anxiety and of Martin Heidegger's existentialist analysis, Professor Berthold supports his view of religious anxiety by demonstrating that "anxiety before God, so far as this is a human experience, [shows] the same structure as other kinds of anxiety."

But, as Professor Berthold points out, even though there be agreement on how to describe the structure of religious anxiety, this by no means implies identical theological interpretations of the data. In fact, seemingly contradictory theological interpretations have been upheld in Christian thought: on the one hand, religious anxiety has been understood "as a genuine desire for God, as expressing the upward thrust of that goodness in man which is not entirely lost by sin"; but, on the other hand, the whole tradition of the Protestant reformers and their spiritual descendants has seen in the data "a reflection of the human situation which is consistent with the notion of man's total depravity."

How does this situation come about? Are theological interpretations so dogmatically determined that they are empirically vacuous, that descriptions of human experience are irrelevant? Or is experience so related to theological interpretation that it can meaningfully mediate such apparently opposing positions?

In answering these questions, Professor Berthold considers in detail the relations of knowledge and faith, and, after drawing a distinction between intrepretation and explanation as types of knowledge, goes on to explore the roles of revelation and reason, and the relevance of experience in mediating theological interpretations. The entire discussion is of critical importance, and offers creative insights into problems central to theology and philosophy. It is noteworthy that the conclusions reached are tested, clarified, and elaborated through an analysis of the work of Karl Barth.

Professor Berthold contends that, historically, experience has played an important role in qualifying dogmatic differences which appear absolute, and that, methodologically, it ought to play such a role in theological interpretation. This permits him in the concluding chapter to offer an interpretation of religious anxiety, based on a model drawn from the work of Freud, which seeks to do justice to the Catholic doctrine of man's natural desire for God, while retaining the insights of the reformed tradition into the dangers of that doctrine.

The originality and depth of this small, excellently written, book far outrun the author's modest hopes to have been able to open new channels of conversation on the matters considered. It will be read profitably by professional and layman alike.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

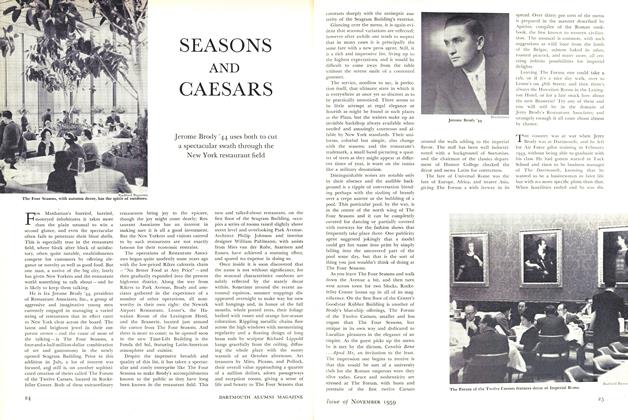

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

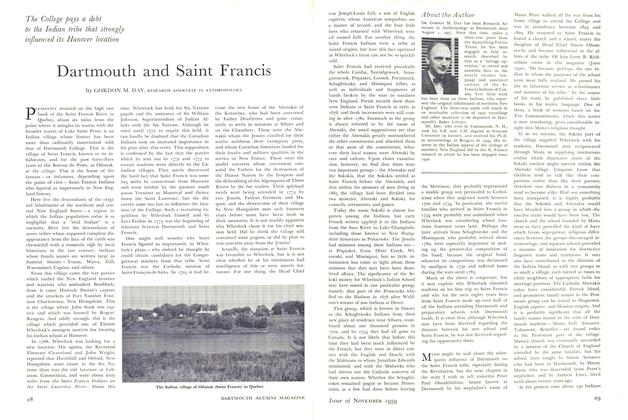

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY

FRANCIS W. GRAMLICH

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

MAY 1932 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

March 1956 -

Books

BooksShelf life

July/Aug 2009 -

Books

BooksWAR AND THE POET

January 1946 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksSHIPS AND SUGAR: AN EVALUATION OF PUERTO RICAN OFFSHORE SHIPPING.

February 1954 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL -

Books

BooksCHURCH UNION: WHY NOT

July 1948 By Rev. Chester B. Fisk.