"Please, sir, could you compare the films of Ernest Thompson with those of Lawrence Kasdan?"

"I could, yes, but I would rather walk down East Wheelock Street naked."

Unthinking, bemused.

Why would a Dartmouth student seriously consider a learned discourse on the methods of the authors of On Golden Pond,Star Wars 2, and Body Heat?

"How much Shakespeare have you read?" I asked. "Or Chekhov or Moliere? Not that I'm an expert on these authors, but as role models they can teach you more about stagecraft and construction in five lines than anybody else. In fact, were I to teach screenwriting, our texts would be certain plays of Shakespeare's. The cutting techniques, the use of entrances and exits, the dramatic emphases of Elizabethan theater more closely resemble modern film than modern theater itself."

That exchange occurred six months ago, when I was asked to take part in the "Dartmouth in Film" program, sponsored by the Film Society. Later that evening, Maurice Rapf, the chairman of the Film Studies Program, asked if indeed I would consider giving a course one term. Vaguely, I agreed, and several months later found myself having to spend the summer on the East Coast, preparing a script for Warner Brothers. I called Maurice, told him that I could teach a course on the process of screenwriting while working on my own project.

"What texts do you want?" he asked. I hadn't thought about that at all, until my wife reminded me of the exchange I'd had with one of Maurice's students.

"The plays of Shakespeare," I said. The trembling began, five minutes after I'd hung up the receiver.

Having written thirteen novels (four published), and sixteen screenplays (four filmed), I believe my "battle scars are worthy of study if not by a medicinal muse, certainly by a Dartmouth student. More, I've lectured enough to know why Dartmouth's film program works, and why the more 'newsworthy' schools (U.S.C., U.C.L.A.) are barren: Simply, at Dartmouth there is more to the study of film than film.

There are Native Americans, Afro-Americans, exceptionally bright young women, physics courses, language courses, snow, fog, Baker Library, bats, squirrels, Collis Cafe, cross-country skiing and women's hockey, and dialogue that has nothing to do with Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, or Spielberg's latest grosses at the box office.

The concerns of the campus, and the film program itself, do not embrace the methods of finding an agent, or a discussion as to whether Dolby sound is a definite advance over 70mm mag. In other words, life goes on at Dartmouth in spite offilm. And it is this very universality of concern that makes a student of film in Hanover a potentially valuable contributor to the motion picture community.

Although there are several courses in film production at Dartmouth, the emphasis is on writing skills. By comparison with most other motion picture departments, this is revolutionary. (Never has the film screen itself been more visually dazzling, and more barren of character and idea. And practically all this summer's moneymakers were created by film school graduates!)

Dartmouth's emphasis on literacy and the humanities is further proof of the motto, Vox Clamantis in Deserto, and that vox, however small, is precisely what can not only save a rapidly dying industry, but also lift the consciousness of an audience. This may seem an obvious point, but my own experience in Hollywood has made me realize that character and, through character, theme the breath of drama and literature-is desperately in need of resuscitation. Therefore, Shakespeare.

We began with Macbeth, moved through Troilus and Cressida, and finished with The Tempest.

By studying line by line the immediacy of the dramatic moment, we began to see exactly what Shakespeare wanted audiences to feel, and exactly how he had achieved that feeling. We traced the psychological beats of Macbeth and spouse, scene for scene; counted the number of entrances and exits in the final battle of Troilus and Cressida, and discovered that the pace had less to do with heroism than with the Marx Brothers; analyzed Prospero's opening expository scenes; and mastered the task of recounting the past while moving the present into the future.

Analyzing Shakespeare's dramatic craft from within the text itself taught us how to read as professional crafters, providing us with the best how-to book ever written. Not only did this method of study enable us to marvel at Shakespeare all the more, but also it gave us a method to study all forms of fiction.

One half of the class was responsible for a structural analysis of three other plays, and the other half had to do original writing. And original the work has been, ranging through a surreal study of the last year of the life of photographer Diane Arbus; a road-film where an angry Thersites encounters Horatio Alger and both trip across America, encountering Jay Gatsby along the way; the strange breakdown and stranger recovery of a left-handed psychic; the life and death of the ultimate assassin in a futuristic Los Angeles; the destruction of an introverted religious scholar by a sixteen year-old psychotic-mystic; the adventures of two dead men who discover that hell has been closed, and so must return to earth...yes, L.B., I could go on.

Suffice it to say, the writing has been more inspired, imaginative, deeply felt, and caring than 99 per cent of what passses for pleasure on the screens of the world.

And all of it took place in a small town in New Hampshire.

Which brings me back to the student's question:

"Please, sir, compare the works of Thompson with Kasdan."

The query, I think, has less to do with lack of critical skills than with the sense of isolation all Dartmouth students have felt at one time or another. But the Film Studies Program, and the writing and concerns of the students themselves, have proven to me how necessary that isolation is, and what a positive laboratory Dartmouth always has been for revealing, and in the course of that revelation, for understanding character. And in the process of that discovery to begin to plumb the extent of one's own humanity.

Stephen Geller '62, screenwriter and novelist, taughtDrama 52, "Writing for the Screen," at the Collegelast spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

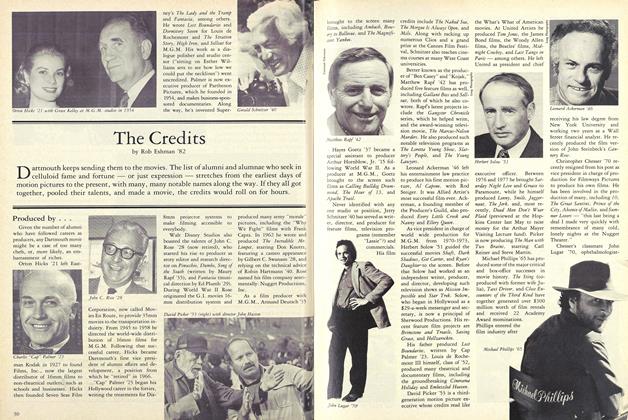

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe West That Wasn't

November 1982 By R.E.

Stephen Geller '62

Features

-

Feature

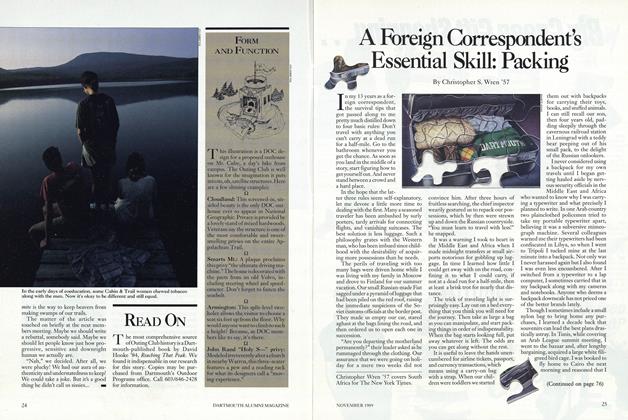

FeatureA Foreign Correspondent's Essential Skill: Packing

NOVEMBER 1989 By Christopher S. Wren '57 -

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Features

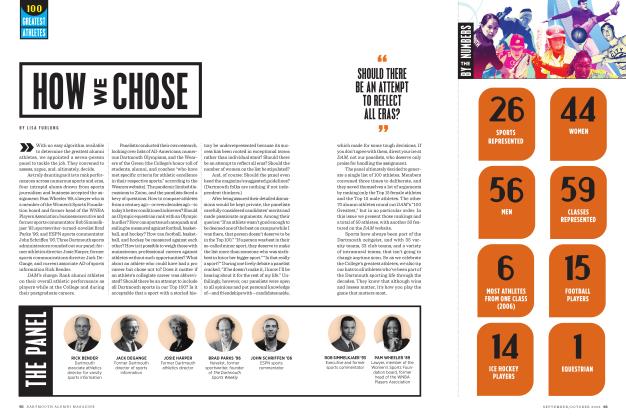

FeaturesHow We Chose

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

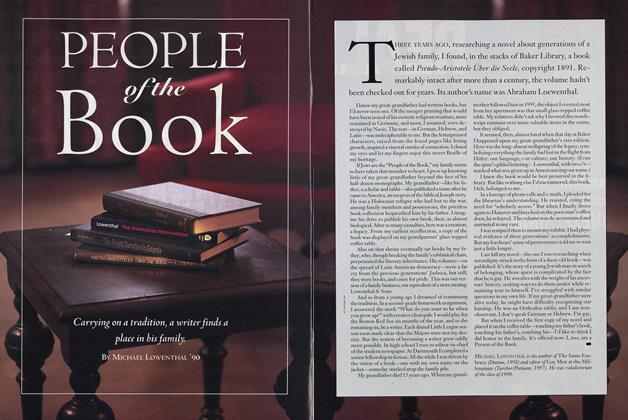

FeaturePeople of the Book

APRIL 1999 By Michael Loventhal '90 -

Feature

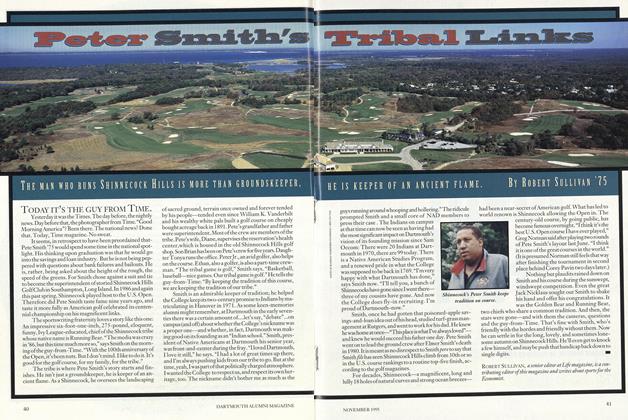

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75