In the late summer of 1966, 28 American teachers and scholars, twenty from the United Kingdom, and one from Canada met at Dartmouth for two weeks to discuss what should be done about the teaching of English. Two books, The Uses of English slanted towards the United States and Growth Through English, suggest that Hanover ushered in a new era of cooperation among educators.

In this large-scale international conference on a basic subject, members included teachers in primary and secondary schools and schools of education and university professors who are specialists in literature, linguistics, creative writing, and rhetoric. Twenty-two psychologists and sociologists visited the seminar as consultants. Dozens of papers were produced, and conferences proliferated with informal discussion at all hours of the day and night. Arthur E. Jensen, Professor of English and formerly Dean of the Faculty at Dartmouth, was Co-Chairman and Director.

Participants wanted to find out what English is, how it should be used, and how best it might be taught. It is not merely that there are almost a million teachers of English, 100,000 of them in high school programs originally so devised that inferior teachers could teach uninterested students under impossible working conditions. Now that half of the students are heading for college, these antiquated programs have clearly become outmoded.

What is English? To the seminar it first appeared as a state of hopeless confusion, not a profession but a predicament. More bound by convention, teachers from overseas were startled to learn that English as taught in America could be journalism, play production, business and social letters, techniques of research, novels and short stories, radio scripts, the use of the library, proper study habits, orientation to school life, career counselling, the use of the telephone, and advice on dating - almost anything spoken or written after a child has been toilet trained. The California Department of Education has classified no fewer than 217 different courses as English. English is World 1 and Universe 2. Or call it the dumping ground of prejudices. Prof. Albert R. Kitzhaber of the University of Oregon, formerly of Dartmouth, makes the point that except for "social studies," which David Riesman calls "social slops," English is the least clearly defined subject in the American curriculum.

Is literature the heart of the subject? Yes, say college and university English departments. But most citizens view literature as an amusing diversion not really needed for the modern world, a puny David weakly frowning at the Goliath TV. Should the emphasis be put on our cultural heritage? Is the goal proficiency in reading? Should functional, expository, personal, or imaginative writing be stressed? How much time should be allotted to rhetoric, the ability to speak tersely, clearly, and persuasively?

At the Dartmouth seminar clashes occurred over educational points of view in England and America, but, even so, understanding was achieved, for Americans upheld the traditional British ideal of intellectual discipline (though actually they wanted an equal amount of freedom), and the British upheld the ideal of individual freedom which Americans have always prized in theory. All wanted both discipline and freedom: the best of both worlds.

Based on the Dartmouth Seminar, TheUses of English by Herbert J. Muller and Growth Through English by John Dixon attempt to repair centuries of educational neglect. The authors are well qualified. Mr. Dixon, Senior Lecturer in English at Bretton Hall College of Education, Wakefield, Yorkshire, was formerly head of the English Department at Wolworth Comprehensive School, London. Now at Indiana University, Mr. Muller, author of Uses of thePast, The Loom of History, and a biography of Adlai Stevenson, has taught English for forty years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

February 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

February 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

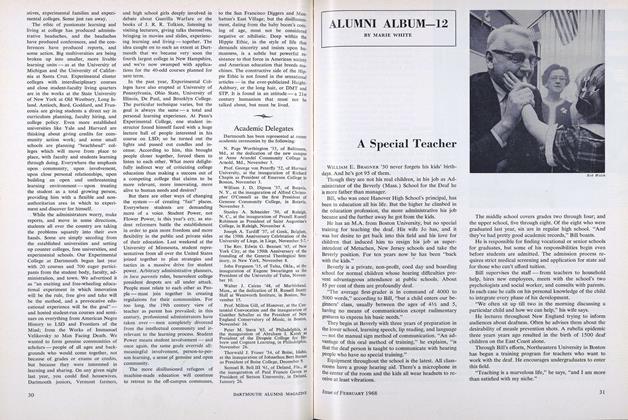

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968