Just the Facts Ma'am

And the Lacks, Sir

THIS year's Alumni College, an intellectual marathon of sorts, assigned itself the task of chasing after an understanding of the differences, or lack of them, between men and women. Professors and students took off on Sunday, August 7, headed pell-mell into the territory of literature, fine arts, and the social and behavioral sciences, and finished strongly 12 days later. The finishing kick was quite unanticipated: the screening, for educational purposes, of an explicit film showing two energetic, intimately engaged senior citizens.

Not counting the nearly 100 children in the junior program, 288 experts on the topic of male-female relations, the secondlargest group of students in the 14-year history of Alumni College, came to Hanover from as far away as France, Panama, and Singapore. That more than half of them had participated in the program before, according to Steve Calvert '68, Alumni College director, "makes things easier. They know how the thing works. They don't complain." One couple, in fact, had attended all but two of the previous programs. There were 25 more women than men signed up, and five couples in attendance had children enrolled in Dartmouth's regular summer term. The senior class represented was 1915 and the youngest was 1974. The Class of 1959 had the best representation - five couples - but there were participants from every class between 1926 and 1963.

Statistics were an important part of the seminars - two of the six lecturers, Assistant Professors Peggy Hock and Lawrence Morin, are psychologists, and one of the lecturers, Dr. Mai-Lan Rogoff, is a psychiatrist. (I wasn't alone in wishing that some of the time spent evaluating studies of rats and rhesus monkeys could have been given, say, to a professor from the Religion Department and a review of the roles of men and women in the Jewish and Christian traditions.) Jim Epperson, professor of English and academic director of Alumni College, and Joy Kenseth, assistant professor of art history, spoke for the humanities. Manon Spitzer, an editor and historian working for the American Universities Field Staff, represented the social sciences. A host of other academic types led the daily small-group discussion sections, and additional lecturers presented special-interest sessions - like "movement and fitness" or computer classes.

Late in the spring students received an arm-load of reading. In the study guide sent to all participants and in his lectures, Epperson asked why Ken Kesey's novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and particularly why its hero McMurphy, "a character of exaggerated masculinity," is so admired. He wondered, rhetorically, whether Virginia Woolfs A Room ofOne's Own, a polite polemic against a male-dominated society, is as valid today as when it was written - or if it was ever valid - and explored the consequences of sexual disguise in Shakespeare's TwelfthNight. Spitzer assigned God's Bits ofWood, a novel by Ousmane Sembene about the independence movement in the Sudan, showed films and slides of African, Asian, Near Eastern, and South American cultures, and compared and contrasted the various roles assumed by men and women.

Hock and Morin gave us SexualSignatures and several reprints from scientific journals to read and, in asking what it means to say someone is a man or woman, considered the complicated relationship between biological and environmental influences on gender identity. Rogoff, who had us read Gail Sheehy's best-seller Passages, discussed the difficulties and consequences of maturing as males and females. Kenseth accompanied her animated lectures on art history with slides of images of men and women in painting and sculpture, asking if the differences between them were determined primarily by sex or, instead, regionally and historically.

Lectures began every morning at 8:30 in the Murdough Center's Cook Auditorium, and after two one-hour lectures and a coffee break, the group split- into discussion sections of about 16 people. School was out by 12:30 - and it was usually the professor who interrupted discussion to say it was time for lunch. Whenever a speaker suggested he cut his lecture short because time had run out, he was invariably answered by a chorus of objections from students. The atmosphere was relaxed, but there was also a sense of impatience. The consensus seemed to be: "This is a large and complex subject and since we have less than two weeks to talk about it, let's get going."

Back-to-school attire was decidedly informal. I don't remember seeing a single tie - except on Director Steve Calvert and the occasional College dignitary who wandered in to socialize during coffee breaks. There were executives in blue jeans, grandmothers in shorts, and "talking" T-shirts abounded. One woman's ample bosom bore the slogan "Women should be in the House..... and the Senate" and a man sported "Dartmouth College: A Tradition of Men in Exciting Positions." Alumni College T-shirts from previous years served as conspicuous status symbols and this year's model, replete with Picasso logo, was enthusiastically hawked by the staff and proclaimed a collector's item when sales lagged.

Advertising and clothing happened to be the topics of one of the first lectures and discussions. Dr. Rogoff showed slides illustrating sexual stereotyping in magazine ads (sexy, submissive women; dominant, macho men) and discussion that day in Epperson's group focused on advertising's propensity to create desire - sexual and otherwise. (Desire, not coincidentally, was the theme of Epperson's lecture that same morning. He referred to it as a "complication" arising from our biological differences.) When someone mentioned automobile advertising, a man in the group asserted that he'd rather lose his wife than his Cadillac convertible. His remark was greeted by applause and hisses and by a fierce, knowing look from a hard-line liberationist who claimed to have successfully "re-socialized" her older, alumnus husband. When we discussed the clothes the women in the group were wearing, a widow explained that women, of course, dressed for other women but they undressed for men.

Professors generally succeeded in provoking discussion. Epperson once observed that "A lot of women are angry, but what about the men? They're not happy either. They're dying! After 45 it's all luck.... It's comfortable for me to take the liberal position. The women go on and on about how abused they are and I nod my head and say, 'Yes, you certainly are.' But every once in a while I launch out and say, 'You're not the one who's abused, I'm abused.' " Paulson commented that when he tried to think of stereotypical feminine behavior he thought of women buying shoes. "Women are taught to be narcissistic," he said. "We dress little girls up and stand them in front of the mirror and say, 'Aren't you pretty.' "

Hock pointed out that the only significant biological difference between men and women is reproductive: "Women menstruate, lactate, and gestate; men impregnate." She also said that the major causes for an individual's development as masculine or feminine are cultural, not hormonal. Morin discussed how fluctuations in their menstrual cycles affected women's tendencies toward aggression and anxiety, but Rogoff observed that, since the incidence of crime among men is so much higher than among women, "Perhaps women have some sort of hormonal protection which they loose monthly, when they sink to the level at which men spend their entire lives." Kenseth's first images of men and women in art were of women as nurturing mothers and men as devouring marauders.

The two sexually explicit movies shown, Radical Sex Styles and A Ripple in Time, were the most controversial presentations in what, I suppose, was a potentially volatile curriculum. Rogoff, challenged about her reasons for showing the films, replied that they had certainly served their purpose of provoking discussion, presenting options, and providing information. She recounted a conversation with an older woman who asked what she liked about ARipple in Time: "I told her that in my naive way I'd like to think I could be making love like that in 50 years, and the woman told me, 'lf you find out, let me know.' " While most of the students in the discussion group I attended spoke positively about the educational and aesthetic value of the film, or debated at what age their children might see it, one gentleman blurted, "I've been waiting to say this all day: Frankly, I thought it was repulsive."

I confess I found reactions to lectures and discussions as interesting as the lectures and discussions themselves. Half-way through the program Epperson announced that he was "suffering from sensory overload" - a common response to the bombardment, day after day, by fact, conjecture, and opinion. I overheard a woman complain to her neighbor, "I want some conclusions, something to hang on to!" and a man gripe to a professor, "A lot of us are angry. You guys don't give us any answers. You recite statistics for an hour and then tell us to take them with a large grain of salt because they were compiled by questionable methods." The same man, a non-alumnus, also told me, "I'm a freeloader. You guys give away a good education for easy money." After a lecture in which a professor did come out and say what he made of the information presented, I heard someone say to a friend, "That was good, wasn't it? It's what we'd been waiting for. [pause] General Motors up or down today?" When students demanded an interpretation of Fellini's film 8½ my neighbor muttered to me, "Why do people need a professor to tell tell them what they're supposed to think of a movie?"

As one might expect, students didn't leave Alumni College with a long list of solutions to problems created by real or perceived differences between men and women. In his well-received closing lecture Epperson suggested that the disappearance of meaningful stereotypes, which previously provided people with answers to the questions posed by their sexuality, is one of the reasons why society seems to be "in a state of sexual fever - a fever that will be broken when we come up with some new models that men and women can share.... Maybe what we need to do is learn to let that 'other' we've suppressed emerge... learn to accept opposites - to be both winners and losers, potent and impotent, madonnas and whores."

The possibility of a shift toward androgyny, as a solution, was a theme pervading the course. Rogoff, in asking if society should seek to encourage or eliminate perceived differences between men and women, suggested that "Perhaps people should be encouraged to take advantage of all their characteristics. Females should be encouraged to be more 'male' and males to be more 'female.' It might be that only then can any true love between the sexes be possible." Hock emphasized that men and women were more biologically alike than different.

It is an idea that takes some getting used to, that threatens a good many identities, and that wasn't overwhelmingly accepted by the students. But, more than anything else, it kept the intellectual fires burning for 12 days. What everyone did seem to agree on was that the time spent in discussion, reading, and listening was just a beginning and that a truce in the war between the sexes means freedom for men and women alike. "I'm exhausted," Epperson said at the finish, "but also exhilarated."

I came having done all the reading, including "Rhythmic Changes in the Copulatory Frequency of Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca Mulatta) in Relation to the Menstrual Cycle and a Comparison with the Human Cycle" and "Sexual Inequality: Men's Dilemma (A Note on the Oedipus Complex, Paranoia and Other Psychological Concepts)." And I came feeling no particular expectations. I was ready for anything short of a sermon on (to borrow a title) "The Mental, Moral, and Physical Inferiority of the Female Sex" - or of the male sex, either. Inferiority, I felt pretty sure, had gone underground (though I doubt whether it is down a full six feet yet). I expected no unfashionable accusations or denunciations, and, indeed, I encountered none.

I confess to not having figured out exactly what I did encounter. Two things struck me. First, the notion of sexual equality seems to have percolated fairly thoroughly through society at large, so that it is discussed with greater acceptance and familiarity than before. Second, I did not hear any one among the participants clamoring to be admitted to the perquisites (much less the responsibilities) of the other sex. That tells me that I did have one expectation, at any rate. And it probably accounts for the slight sour taste of disappointment I experienced as I sat down to write up what I had thought would be a juicier story than in fact it is.

We began bright and early of a Monday • morning, herded into the lecture hall by the clanging of a big brass school bell. I found a seat, fished out pen and paper, and took a quick survey of the audience. Gray hair seemed to predominate. Then it was time to turn my attention to the podium, where the first lecturer, Professor Epperson of the English Department, had arrived, clad in poison green.

"Men and women are different," postulated Epperson, "at least biologically. Physically and mentally, they desire each other. Desire has the effects of illness, which is cured by coming together in mutual harmony and trust. The differences have created sexual stereotypes, which are then imposed upon us. The restrictiveness of stereotypes leads to a political connotation in the differences between men and women, or a politics of sex."

Around me people took notes, doodled, yawned. Next to me a note-taker carefully labeled the day's notes with the lecturer's name and sex. The first lecture ended to appreciative applause, after which Dr. Rogoff, a psychiatrist wearing a blue suit, took the podium. The audience seemed to shift posture a little; some threw their heads back to gaze at the ceiling, perhaps in deep consideration of what was being said. One participant peeked surreptitiously inside a notebook, where there was a newspaper.

And so it went, pretty much as one remembers school to have gone. We heard from the psychiatrist that it is easier to demonstrate belief in the differences between men and women than it is to demonstrate the differences themselves. One of the two psychologists declared, "I have data to show - if I go out on a limb - that women are going to be more fickle, variable, inconstant than men." The other said, "What is the difference? Biologically, not much. The hormones? Well, they will shift disposition slightly, but only slightly. The brain difference? Probably it involves the reproductive functions only - after all, with electricity one can make a male rat's brain female. Men and women are born equipotential. Rearing determines them."

One lecture included slides of paintings, shown so we might guess at the sex of the artists. "It's so hard to tell," my neighbor whispered in the darkened auditorium. "That one is too drab for a man," said somebody, and someone else laughed. As a group, we guessed five out of twelve correctly and thereby substantiated the art historian's opinion that sex does not determine artistic ability.

The computer gave us the statistically significant results of the masculinity/femininity questionnaire we had all filled out. We discovered that the women in the group felt that there was only one quality with respect to which men and women are at opposite ends of a spectrum: skill in business. The men in the group felt that men and women differ widely with respect to aggression, emotionality, hiding of emotion, objectivity, dominance, enjoying math and science, skill in business, crying, and expressing tenderness.

The lectures told me a lot I already knew and a good deal I didn't know. Womb envy, apparently, is a recent psychiatric discovery (hearing which, the audience tittered slightly). A study of 1,000 homosexuals disclosed that the only significantly common factor among them was a cold, undemonstrative, unnurturant, or absent father. The empty-nest syndrome was debunked: Women whose children have left home are the least depressed women; the highest depression rate among women occurs in households with children under six. The majority of women do not, after all, experience multiple orgasms. And simultaneous orgasms, far from being the norm, are rare: One partner's climax usually occurs before the other's.

I also overheard, on the stairs and over coffee, little slices of Alumni College life. After the lecture on Ken Kesey's novel, someone in front of me said, "I didn't think that book was all that sexy!" "Not sexy," came the correction, "sexist." Toward the end of the session, as the bell jangled for discussion groups, one portly soul rose stiffly and said to a neighbor, "Well, I have to go upstairs now and be insulted by more young women." "Yes," replied the neighbor with a wink. "We 'grayhaired, power-hungry business executives with ingrained prejudices' take a lot, don't we?" And one day I heard the following patient explanation: "As Jung saw it, each man and each woman has within him the opposite principle," and this rather sullen reply: "What I want to know is, are we being sold on this androgeny thing by Madison Avenue and maybe it won't be around anymore in ten years?"

The deepest conversations were, of course, heard round the discussion tables. One group began with a question regarded as "particularly relevant to Dartmouth."

"How do men change in the presence of women, and how do women change in the presence of men?"

No one responded right away.

"My Dartmouth boys," continued the discussion leader, "I mean, my students - excuse me, men - who are anticoeducation tell me that something is vanishing with coeducation."

"Yes. It's a shame. Women are here now, and there's no freedom of expression any more."

"You hear that all the time: Boys will be boys. College is a time to let loose. It's four years up here in the woods, when the police look the other way while you drink a lot, maybe try a little vandalism."

"What do men do together? What's so fascinating about men's bars?"

"Well, let's talk about Mory's, the bar at Yale that used to be all-male. Why did women sue to get in? The food was mediocre and the beer was the same as everywhere else. The real thing was that at Mory's power is exchanged. High-powered governance and business contacts are made at Mory's over lunch. When a men's club is a seat of exchange of power and governance, it is not okay for it to exclude women."

"I didn't see those politics at Mory's. I don't buy that argument about power. I think the women who sued did it just because it was a challenge. And I think the resistance to them was simple resistance to change."

"I agree. The female rebellion is a rebellion against second-class citizenship. It's just normal for people to resist change. Don't look too deeply for the reasons."

"But one wants to understand the strangely passionate desire to keep Dartmouth all male."

"Well, the alumni were afraid their sons would be discriminated against."

"They have daughters, too."

"There were practical reasons. Women alumni don't contribute as much as men alumni."

"That simply is not true. Harvard studies show that women give the same percentage of their incomes as men do."

"Well, I don't know about that. I don't think I believe that study. Besides, it's not percentages that count, it's dollars."

"Here we are at the economics question. In this society women don't make most of the money, so they can't give most of the money."

"As a college treasurer, I can tell you that it's the dollars that count."

"Anyway, one doesn't want to alienate the giving alumni while the women wage their war for decent salaries."

"What is it that is alienating about women?"

"Why," began another discussion session, "are there so few men in this group?"

"Will we see things from a male perspective?"

"What about men? Are men changing, too?"

"The male inner message is, 'Stay on top, or you'll be on the bottom.' Men can't ever relax. They can't show weakness ever, or cry, or be helpless."

"My daughter is a female dentist. And one of the things she found really distressing in school is that crying is not permitted to angry interns."

"She's got to learn to swear a little."

"Do women really cry in public?"

"Of course. Women cry when men would get angry."

"My teenage sons can cry. They feel free to cry."

"They do? Among their peers?"

"Oh, well, no. But at home, they certainly can and do."

"My husband won't let our boy cry."

"What does he do?"

"He shouts, 'Stop that! Boys don't cry, do you hear!' He's not at Alumni College, either."

"That brings up another question. Why did those of us who came come?"

"I came because I want to learn how to deal with the invasion of women executives."

"You said 'invasion.'"

"Yes. I meant it."

"Are men really threatened by the Women's Movement?"

"Well, I am. I worked hard all my life, and I built up a successful business, and the whole point and purpose was for my wife, whom I love. The children are all grown up and graduated; and now my wife has a job. I come home, the house is empty, there is no dinner on the table, and I am hurt, and angry, and confused."

"You should get a mistress."

"That's not the point. I love my wife. I even told her we should adopt some more children. There's plenty of money. She said we have already raised our family. She doesn't want to go through all that again."

But perhaps the most energetic discussions were those concerned with two films shown near the end of the session, films which broke the taboo against open acknowledgement of the nature of the sexual act itself.

"I have always said that at every Alumni College they have tried to shock us. But I have never, never had a shock like this one, this movie."

"I left when it began."

"Why was it made? Who was buying it?"

"He was 62 and she was 58. And they weren't married. Right there you don't have normal sex."

"It was filmed to show techniques available to older people whose sexual reflexes have undergone the natural slowing process of age."

"I brought my mother with me today can you imagine? My mother. She kept saying the woman was simply a prostitute. I kept asking her if she wanted me to take her out. 'No!' she said. 'I'm not looking!'"

"There was an older couple, in their seventies, sitting next to me. He seemed pretty distressed. He started singing when the couple began to undress. When the woman started using the vibrator, his wife leaned over and whispered, 'What's that? What's that thing for?' 'I don't know,' he hissed back. 'I don't know what it is!'"

"Where does morality fit into this? Is anything acceptable?"

"What was immoral in the film?"

"The filming of the couple having intercourse. The whole concept of pornography is immoral. I don't believe in pornography. I believe in sinfulness. Excesses. If those people in the film are sick, they are not sinful; if they are not sick, then they are sinful."

"Who got hurt? What's the sin?"

"You teach at Dartmouth. Do most of the students you come in contact with today feel that sin is passe to talk about?"

"Yes."

"Look. In seeing and discussing these films, we as a group are certainly being very liberated - or we're pretending to be. Four-letter words, masturbation, vibrators - such things could not have been talked about, much less seen on film by all of us together in 1966."

"It's true that it is an assault of a kind to see such 'forbidden' things, especially in a large group. But it is education. Both films were honest documentaries. And it is also permission. Showing things outright, in a group, is a way of giving permission."

So what does all that add up to? Epperson thought it was "the best Alumni College session yet, in every way." Had it gone as expected? Or had it taken odd turns? "I did think," said Epperson, "that we would get into more discussion of the Women's Movement and the significance of it. And I was not prepared for the undercurrent of interest in homosexuality. Is it because of Anita Bryant? Because the participants have friends who are homosexual? Children? Themselves? I heard a lot of people ask about 'the cause of homosexuality,' and several people asked, rather revealingly, 'Can homosexuals be rehabilitated?' "

Rogoff's evaluation differed from Epperson's in the same way the psychiatric lectures had differed from the literary ones: in a greater concern with sexual roles than with sexual intercourse. The good doctor spoke of the presence of an overpowering assumption, perhaps inherent in the topic, that yes, we ought to exchange existing "gender stereotypes for others that do not codify so many spheres of behavior by sex. "But no one got a chance to ask whether we should," said Rogoff. "I think there was a strong conservative element present which didn't find any opening to speak up. The men especially were often silent. I think perhaps that's because men are only just beginning to realize that their stereotype isn't any more functional, really, than women's is. Ten years ago the women were where the men are now —just beginning to get really angry at being lumped into a stereotype. Remember the angry lecture about being 'put down' as a male? That's the sort of thing I mean. I was sorry that the . provocative lectures came at the end - that was a mistake. We left them discussing sex. That's not what I wanted. I wanted to leave them singing 'Androgeny!' Men and women talking to each as people."

And I? Well, as I say, I felt the thorn of disappointment. There was a pervasive reluctance or inability to see beyond the tantalizing, mesmerizing subject of sexual intercourse to the vastly wider subject of all the spheres of behavior that in this society are regulated by sex. Epperson's fascination with sexual desire and lovesickness as the crux of the relationship between men and women suggested, for instance, that men and women don't do anything else together. And the involving and inflaming effect of a couple of filmed scenes of coitus was a surprise and a disappointing indication that the level of consciousness about sexual justice is in many cases no higher than the keyhole to the bedroom door.

And I didn't hear any passionate desires expressed for a real androgenous state of mind. Perhaps for good reason: it's an ideal not easy of achievement. I have to be careful here, because I am projecting my desires and my situation, perhaps inappropriately. My own highly satisfactory heterosexual marriage is fiercely egalitarian. Both of us are earnestly committed to breaking out of the restrictive and separatist patterns of behavior that were inculcated in us as members of a sexually exclusionary society. What we have discovered is that to take - to want to take - your share of responsibility for those things you were not raised to feel responsibility for is the most difficult, and the most important part of any serious attempt at achieving sexual justice. Many a man has cooked a meal and changed a diaper; many a woman has made some money and seen to the car's repair. But to take responsibility for those things on some day-to-day basis, for some real period of time, so that the other can count on you for it, is another and a harder thing.

I sense that it isn't fashionable nowadays to talk about responsibility, just as it isn't fashionable to speak of sin any more. Whenever I talk about responsibility, I get the feeling that people groan inwardly at the heaviness, the seriousness of it all. I think it suggests to many an insupportable invasion of personal liberty. But license is not the only source of fun and of joy; they Jive also at the heart of responsibility. I get a real charge each month out of paying the mortgage, with money I have earned. It makes me feel terribly grownup, and that it does so gives me the giggles about myself. And one of my most treasured memories is the telephone call I received at work last winter, when the baby was some four months old. It was my husband, wild with excitement. "Shelby!" he shouted. "The baby just ate a whole inch of banana!"

When our assistant editors onemale, one female suggested thatthey jointly cover the 14th AlumniCollege, it seemed the sportingway to approach this year's theme.There was also the potential for agood literary spat, hand-to-handcombat across columns. But forthe writers and the participants,the war of the sexes turned into atruce.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

October | November 1977 By Sanborn Brown -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

October | November 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October | November 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson

Shelby Grantham

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

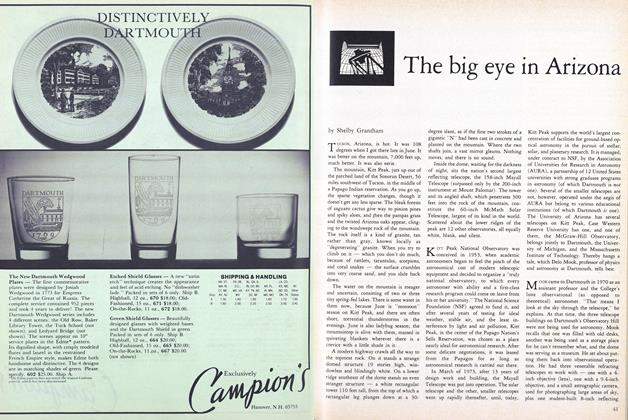

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDinesh D'Souza '83

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN PFISTER

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

OCTOBER 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45