By Carl Bridenbaugh'25. New York: Oxford University Press,1968. 487 pp. $10.

In studying the beginnings of the American people, Professor Bridenbaugh has put his emphasis on the activities of ordinary men and women, in accordance with the principle that "history is about chaps." His subject is the great migration from England to America in the early decades of the seventeenth century. Why, he inquires, did so many Englishmen elect to abandon their homes to undertake a perilous voyage across the ocean, and how was this adventure accomplished? In seeking to answer these basic questions, the author scrutinizes the propaganda on which the emigrants were sustained in their hope of a better life — and then the less inspiriting fact: the grim passage, lasting anywhere from five weeks to several months, and sometimes made hideous by cannibalism in the face of starvation; and the dejection and disillusion on arrival in the brave new world.

The wanderlust characteristic of modern America has its roots, evidently, in the willingness of these early voyagers to endure terrible hardship, in pursuit of their desire for change. This desire is explained partly as resulting from a growing weakness in the structure of the family, as also from a growing ambition for worldly success. The typical emigrant, though poor and often uncouth, lived in the conviction that "Time is money." It is part of Professor Bridenbaugh's purpose to tell how this vexed and troubled person made his living, and how he was frustrated in making it, as by enclosure of the land.

As the book goes forward, it becomes obvious that the ostensible story is a pointd'appui: what Professor Bridenbaugh is really doing is writing a social history of the English people from the last years of Queen Elizabeth to the outbreak of the Civil War. The heart of this story is the living and dying of townsfolk and countryfolk — the food they ate, the smells and diseases that afflicted them, the dour religion they professed, and the dubious amusements, like bear baiting and bull baiting, with which it was tempered. Football, then as now a species of controlled mayhem, had its adherents. Crime and violence flourished. Brothel houses, of "six-penny whoredom" stood next door to the magistrate. Drunkenness was a national problem. In 1641, a company of young men at Dartmouth "went to the country to fetch home a May-pole . . . the Pole being thus brought home and set up, they began to drink healths about it, and to it, till they could not stand so steady as the Pole did." The more things change, the more they remain the same.

It is not difficult to imagine the outraged moralist making up his mind "to sail west-ward where the land seemed bright." That fateful decision and the consequences ensuing from it have found in Professor Bridenbaugh an admirable chronicler.

Mr. Fraser is Chairman of the Departmentof English, University of Michigan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

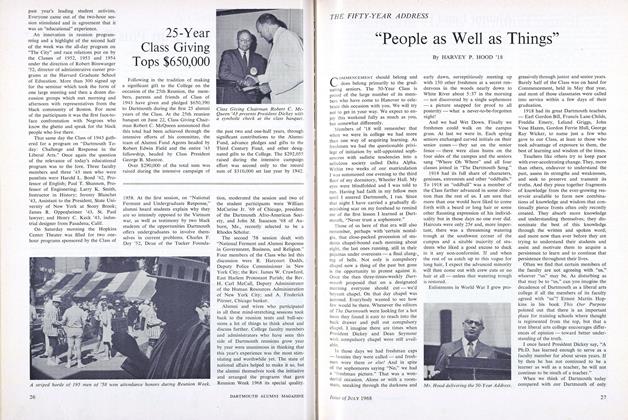

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

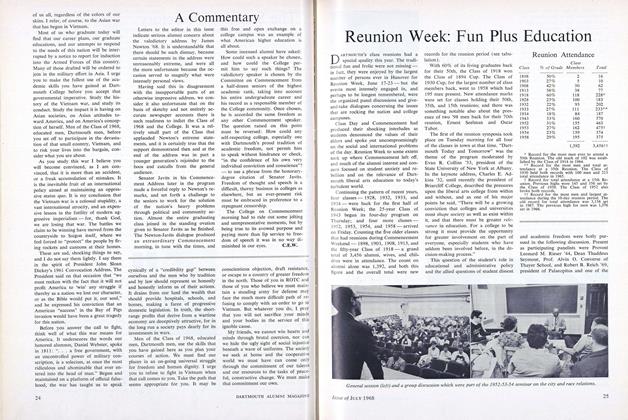

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

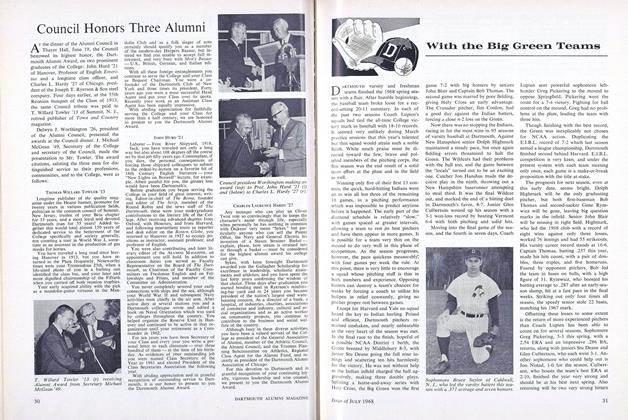

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968

RUSSELL A. FRASER '47

Books

-

Books

BooksUNDERGRADUATE

NOVEMBER 1931 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

DECEMBER 1966 -

Books

BooksTHE "WHY" OF MAN'S EXPERIENCE,

January 1951 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Books

BooksTHE STATES AND THE NATION.

January 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

October 1941 By Harry L. Purdy -

Books

BooksSons and Fathers

October 1975 By ROBERTH. ROSS '38