THIS article arises out of the curious notion of my friend the editor that I am, though on the one hand a notorious conservative, also on the other a generous - he even said "liberal" - grader in my Dartmouth courses.

He can be forgiven. I deny the description. Though the actuality is complex. And the entire question goes to the heart of the teacher's conception of his function in the liberal arts.

Just what are grades? How do they function in the concrete situation of an academic course? What do they mean? It is by no means the intent of these questions to suggest that grades are not important. As a matter of fact, I think that they can be very important. Still, and though I suppose the entire matter is different in the exact sciences and in mathematics, it seems to me that a grade in the humanities is a problematical and sometimes complex phenomenon.

Before we go more deeply into the question, I think I can set forth briefly a simple schema, one on which I think virtually all of my colleagues would agree. After I do that, however, things will get more complicated.

ii

In my opinion, and I think agreement on this is virtually universal, an "A" student essay must contain no serious mechanical or stylistic flaws; indeed, it must be written with at least a certain flair. It must also contain something striking, fresh, original. As an undergraduate effort, it need not be publishable, but the atmosphere of punishability should surround it. No doubt other professors have their own modes of reaction, but for an essay to get an "A" from me, I have to say, as I read it, "Now that is really something."

A "B" essay contains no serious mechanical or stylistic flaws, but lacks the striking quality of the -'A" paper. It does not sur- prise you. "B—," "c," and lower grades reflect serious shortcomings of form or substance. I must say that when one of my students at Dartmouth performs at less than the "B" level, I tend to feel that he or she ought to be doing something else, somewhere else.

iii

Still, all that is pretty obvious. For a college professor, the question occurs at this point: what is the best way to get your students to perform at the "A" level? Just what are you trying to accomplish with these students? Clearly, you are trying to evoke the best possible work from them, make them discover their full potentiality. But how do you do that?

The two professors who in various ways influenced me the most I encountered during my junior and senior years at Columbia College, and later on I worked with them as colleagues in the English Department there. Lionel Trilling and Mark Van Doren were both powerful and brilliant men, and they had different and even opposite attitudes toward grading, as, indeed, they had about most things.

Trilling was tense, rigorous. He smoked a lot of cigarettes, like some kind of French intellectual. He generated an atmosphere of intellectual strenuousness, a mode of puritanism. Going through a poem or an essay with him was an act of intellectual self-exposure. He worshipped Mind. To be as intelligent as Trilling felt you should be was an infinitely receding goal. Any lapse received severe treatment. Trilling was a tough, grudging, sometimes even punitive grader. He positively hated mediocrity. Naturally, his best students worked very hard for him, producing excellent work, desperately seeking to earn the approval of the Master.

Mark Van Doren, as I say, took a quite different approach. A poet and a critic, he liked to "see" things. He would "see" marvelous things in Dante, Homer, Shakespeare, or Cervantes — things which were really there, but which you yourself did not see until he saw them. He seemed to see things for the first time, whatever it was he looked at. He always seemed to be saying: "Look. Don't you see? Isn't that marvelous!"

In class discussions, Van Doren could lead a student - even some honest yeoman from the basketball team - to the point where the student, mere flesh though he largely might be, actually, suddenly, "saw" something freshly for himself.

In grading essays and awarding course grades, Van Doren gave mostly "A"s and "B"s, though he would of course severely penalize sloppiness or incompetence.

The point is, however, that his students really did produce "A" and "B" work. They worked at least as hard as Trilling's. They knew that if they did produce their best work, Van Doren would "see" what they had done, celebrate it in his written comments — and it was no light thing for an 18-year-old to be "seen" and celebrated by Van Doren. Sometimes, indeed, Van Doren would see things in a student essay, make connection, that had until that moment been only latent, not fully realized by its student author. He would thus improve an essay in the act of reading it.

iv

Returning to our key question: Which approach evokes the best work from undergraduates? Which is the most educational, bearing in mind the derivation of the word educate from the Latin meaning "lead out?"

I am not sure of the answer, and maybe there is no answer. Trilling might have been more effective with some students, Van Doren with others. Both men were shaping influences on men who now hold important professorships, run magazines and publishing companies, run TV networks, win prizes in poetry and fiction.

For myself, I lean toward celebration and encouragement. People — and students are people — like to be appreciated and encouraged. And I like to do that. I find that it evokes good work. I am the least puritanical of humans. For me existence, and literature as part of existence, is pleasure or it is nothing, not worth talking about. I simply will not teach and expect students to be interested in something that does not give me pleasure. I make it clear that I expect student essays to do so too.

Now there are, of course, different ways of being rigorous. You can affect a formidable mein. You can smoke a lot of cigarettes nervously. You can act as if the person you are talking to is boring. Nor is it difficult, after all, to say to a student: "C minus." That is, in effect, scram. If I did that, come to think of it, I could probably put in more time on the tennis court or the ski hill.

It can be more rigorous, though in a different way, to make the student, through a process of evaluation, celebration, and "seeing," produce the best possible work. When you succeed in doing that, you do find that you are awarding good grades, awarding them because they have been deserved.

When he is not opening the eyes and minds of Dartmouthstudents at Sanborn House — or skiing or playing tennis — Professor Hart is enlightening newspaper readers across the land through his syndicated column.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

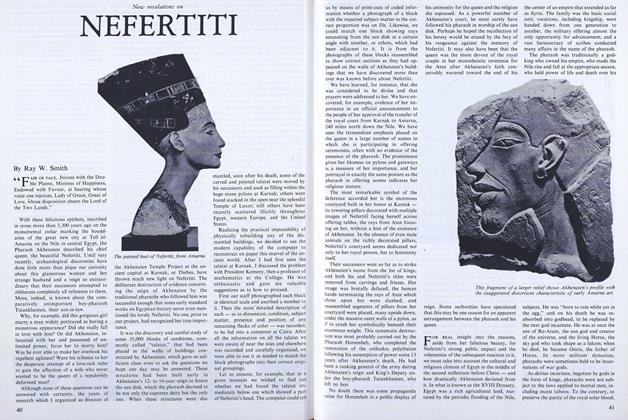

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R.

JEFFREY HART '51

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

June 1981 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June • 1988 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Books

BooksGODWIN AND MARY: LETTERS OF WILLIAM GODWIN AND MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT.

JULY 1967 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Books

BooksSparing No Expense

June 1975 By JEFFREY HART '51