From reading course journals and hearing discussions with visitingdirectors, a Dartmouth film-course instructor describes what students thinkabout movies and movie-makers

You may think you've heard enough about youth's love affair with the movies but you can't escape the consequences. Hollywood itself has had to write off millions of dollars in projects which were, if its estimates of today's audience are correct, not sufficiently "youth oriented." And as parents, especially if you have youngsters under 17, you are constantly being badgered about "new" movies (like Woodstock, which is rated R) because your children can't see them unless you take them.

The effect in educational circles has been equally disturbing. Today, a major college or university that doesn't have at least one course in film aesthetics or production is probably looking for the money and personnel to launch it — due to undergraduate pressure. Dartmouth, which recognized movies as a legitimate academic subject as far back as the 40's with a screenwriting seminar by Professor (now Emeritus) Ben Pressey, offered five courses this year and the students are clamoring for more. One student went so far as to request a special film major for himself - and got it.

What follows is, for the most part, the viewpoint of students on movies as expressed in journals required for two courses I taught last fall, or in their recorded discussions with film-makers who visited the campus.

The invasion of colleges by movie people, let me add, is booming. I know a special effects man who has successfully peddled a three-day technical seminar to a lot of schools and a critic who makes more money lecturing to students than he does from his reviews. Some of the visits are labors of love and some, possibly just as instructive, are for personal promotion. Russ Meyer, for example, a well-known skin-flick impresario, recently attended a festival of his films at Yale and conducted a discussion on "pornography and sex in cinema" for the Law School.

Dartmouth, despite its isolation, has attracted many visitors from the profession and venerable Choate House on North Main Street has been known this year as "Movie Manor." I occupied Apartment 1A in the fall and when I moved put, the distinguished director, Joseph Losey '29, moved in. This was his first extended visit to the U.S. since the infamous movie blacklist of the 50's, and he came to Hanover for the winter to give a course for 90 undergraduates on The Role and Responsibility of the Director. After Losey came Arthur Mayer, the youthful octogenarian whose Drama 61 (Film History) has been the backbone of film study at the College since 1964. And each of us invited others from the industry to participate in our classes.

There are benefits for the students in this exchange, but professionals who expose their work or ideas to undergraduates, as most visitors do, need thick skins. To quote Losey after his first two weeks: "The audiences, particularly as regards my own films, I find such a mixture of concentrated attention and tiresome schoolboy horseplay that it is hard to take."

Indeed it is, but that's the risk of confrontation with youth. We take it because they outnumber us —or perhaps because we like them and know that in the long run they'll make better movies and run a far better world than we.

The film companies themselves are anxious to make contact with college audiences these days. During my tenure, for example, National General let us preview one of their important releases, A Dream of Kings. They even provided ten copies of the novel on which it was based so that students could write their own adaptations before seeing the movie and discussing it with screenwriter lan Hunter who came to Hanover for the screening. It was a splendid educational experience but the reaction to this Anthony Quinn vehicle about what seemed to the undergraduates to be "middle-aged creeps" was certainly not encouraging.

As one student wrote in his journal: "It's beyond any contortion of my imagination how a bad book like this could even be approached as a movie."

A preview of Paramount's costly TheMolly Maguires, arranged by writerproducer Walter Bernstein '4O, raised other problems. The youthful audience was with it all the way, never laughed in the wrong places and gave it a big ovation — which, in my opinion, this tense, eloquent period piece deserved. But the film's press agent, after listening to the student discussion which followed, wasn't satisfied. "They liked it," he said, "but will they go out and tell their friends to see it?"

Entries in student journals indicated that they probably wouldn't - and returns at the box-office, regrettably, prove the point.

"Why go back to 1870 when you have 1970?" said one. "Easy Rider made it because it's about today. Maybe Molly Maguires is better written, acted and directed, but for the moment that isn't what counts."

This is precisely what Bernstein feared when he brought the film to Dartmouth. Before the screening he told the students, "What's good about this picture is ours - and what's bad about it is ours. It's our picture and that's rare. But it's the expression of two middle-aged men - a writer and a director (Martin Ritt)."

And, apparently, in today's market, that's a liability.

But there are hazards for younger film-makers, too, as Barry Brown discovered when he showed us an answer print of The Way We Live Now, his forthcoming United Artists release. Brown is in his early thirties and has had a successful career as director and photographer of hundreds of documentaries and TV commercials, but this is his first feature — and he wrote, directed, photographed and edited it. He would have cut the negative, too, if he'd had the time.

"I believe that a film should be made with your own hands," he told the students. "I believe this is a plastic medium — manual in the sense that painting and sculpture are manual, but you work with actors and other human beings which makes it unique."

Brown was eager to convince his listeners that his way of working, in which he does everything and with his own hands ("like Michelangelo," as he put it), is the only way to make films if they are to be a true expression of one man's viewpoint and talent. "You spend a couple of years and you have an art object that fits into a couple of cans that weigh seventy pounds. It's all yours. Sure, you can hire a bunch of craftsmen and direct them but they'll stand between you and that seventypound thing I brought up here in the trunk of my car."

For film buffs already addicted to the auteur theory, this was heady talk and Brown's enthusiasm and charisma created an aura of eager and willing anticipation. But, as one student said on his way to Spaulding, "I sure hope it's as good as it sounds."

For most of the youthful audience it wasn't. The Way We Live Now is about a successful but alienated young advertising executive who leaves his wife and daughter and tries unsuccessfully to find a better formula for love with an assortment of other women, until he concludes, like Macbeth, that his life signifies nothing. It didn't signify much to the students either. They admired Brown's technical facility and stayed around until the janitor threw them out talking about zooms and 360-degree pans, where lights were hidden in real locations, and what kind of camera was used for a 500-frame-a-second slow-motion shot. But they couldn't relate to the thirty-ish hero and his problems.

And here are some comments from the journals:

"Barry Brown is an egomaniac. He also makes films. Furthermore, he talks about them and praises them before showing them. After that, even the greatest film ever made would be a letdown. But we liked it because it was the artistic creation of one man."

"His do-it-yourself mania is a crock. It's like a novelist cutting down a tree he grew with an axe he made so that he could manufacture his own pencils and paper before writing a novel."

"An egotistical and badly acted bomb and yet I think this film made as great an impact on me as any film I've ever seen . . . because I felt if someone gave me a million bills and told me to go make a film I would very likely go out and make the same kind of shlocky mess. I mean, if that is what it looks like when you spill your guts out on the screen, forget it. I'll get a job as a bricklayer, somewhere."

Joe Losey had more gratifying results when he previewed his new movie, Figures in a Landscape, this spring. "I was rather happy," he said, "with the reaction of a predominantly young audience. I don't know whether it was out of politeness to me. I trust it wasn't, because on other occasions the reaction wasn't very polite at all."

Nevertheless, some of the sharpies in the audience found things to criticize —like mud on the face of an actor in one scene that was missing in the next. When I listened to the taped student discussion in the offices of the film's distributors, their p.r. man said, "Thank God, we don't face audiences like that all the time."

SOONER or later, all visitors ask which films students really do admire these days. The answer last fall usually included Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy, Alice's Restaurant, Medium Cool,Sterile Cuckoo, the very movies which were at the time most successful at the box-office.

As Bernstein said, "That's a twist!" But it's the twist that launched the industry on its current youth kick.

There's difference of opinion about all these movies, except perhaps ButchCassidy which, if not the most admired, was certainly the best liked. But they can be discussed at length, along with many foreign films and especially the works of Jean-Luc Godard who was featured in a retrospective by the Dartmouth Film Society last fall.

Here are some comments from the journals. On Butch Cassidy:

"A type of never-never movie where they didn't have to die in the end. It would have been incredible for them to have shot out the entire army a la Clint Eastwood and go straight to Australia to raise sheep. Best film of the year and an unpretentious piece of pure fun."

"Material is only adequate for 30 minutes — like so many movies these days. Guess they decided if you make a film about two guys who just drift along, that's what the film should do, too. But it works."

"Favorite movie of the year but why that 'Raindrops Falling on My Head' during the sunny bicycle riding scene?"

On Midnight Cowboy:

"Best film of the year but some scenes are weak - like the flashbacks and the party freak-out."

"Schlesinger used too much style and the wrong style for a simple, really sentimental story, borrowing a style that was o.k. for Dick Lester and Petulia and its urban sophisticated people but not right for the simple people in the simple male love story he is telling."

"I was tempted to walk out. After three hours wandering around Boston looking for a room I went to the theatre to relax. $3.00 was the first jolt. The scratchy print was the second. Then it was so depressing and Hoffman was so good that I hated it. Being human and hearing how everyone loved it, I questioned my opinion. Maybe it was frustration. I'll see it again."

On Easy Rider:

"The shortness of the film gives us the time and energy to deal with ourselves. We become extensions of the film. We carry the weight. It's us and it's our country. The fact of the movie gives us power."

"I don't like exhibitionism with a chip on the shoulder, so Peter Fonda playing himself broke the film for me."

"I empathized with the characters at the end. That was no Hollywood illusion. That's what's so frightening."

"Seeing this stoned is like seeing a real world when you're stoned. You wanted to be stoned because you knew you would like it if you were — and that would make it easy to see what the stoned see and do and think about."

"An expensive Fonda home movie but thanks to political appropriateness, more than that."

"I still can't shake my dislike for films that must kill the main character off in one way or another to end the film. A pity in this where everything else seems so natural and unforced."

Students were exposed to eleven Godard movies, only one of which (Breathless) ever made the grade at the box-office in this country. Some of their comments explained why:

"Godard can explore more ideas per foot of film than any other contemporary director. But he compromises his literary integrity for no one and consequently limits his audiences tremendously."

"His dialogue is too real — one step above Andy Warhol. He really captures reality and it's as exciting as capturing a tooth paste tube."

"His men always chase the women. The choice is always hers. Belmondo in Pierrot is the poet a bit teased and dominated and occasionally cockchopped by the breasty, leggy Karina. No wonder he blows himself up."

"One must work extremely hard to understand him and, as with anything one must work for — even if you're helped along with very good grass — the result means more and sticks more than in the whole mass of easier films."

One by-product of the Godard orgy was a visit to the campus by the well-known American director, Don Siegel — which sounds like a non-sequitur but isn't because he's actually a character in one of Godard's movies (Made inU.S.A.) and a cult figure with the French cineastes. Besides, we'd also seen his Invasion of the Body Snatchers and spent three weeks in class on a scene-by-scene, cut-by-cut analysis of Riot in Cell Block 11 (both produced, incidentally by the late Walter Wanger '15).

Siegel has the anti-establishment viewpoint that undergraduates can relate to. "Producers are a dying breed," he said (although he went out of his way to describe Wanger as one of the few he had known and admired). "The director should be the producer.... Cameramen claim they paint with light but most of them are glorified technicians. ... Did you ever meet a distributor who studied to be one? They're the most ignorant people in the world.... Writers are important but we can't photograph pages."

He admitted that the existence of a Don Siegel cult was flattering. "I'm pleased that the youth in France, England and here find some identification with my films and like them. But I don't make films for the cult. That would be too precious. And now that I'm out of the low budgets, the Cahiers people and those at the British Film Institute who liked my films before may loathe them."

When asked the usual question about how to get started, Siegel, who himself made it the hard way, insisted that the movie industry is made to order for those who start at the top. (Walter Bernstein gave similar advice when asked whether it was better to go to a studio or a bank to get money for a production. "It's better to go to your mother," he said.)

IF you're wondering whether these confrontations are worth the effort, consider this journal entry:

"I'm still impressed that people like this are actually taking the time to come to Dartmouth and talk to me about their films. It's great. The most valuable learning experience I've ever had."

And it's valuable for visitors, who find out what students like and hate. For example:

"I hate movies that go all the way around the barn and back to avoid saying a bad word. Like Sweet Charity. It takes about a minute of film time to avoid saying 'whore' on camera — just to get a G rating. That's not the art of making movies; that's the business of making movies."

"There aren't enough movie artists. Unless you're a Fellini, Bergman or Godard you simply can't be given your head. It's too big a risk. In painting or writing, it's o.k. You do a lousy job, you tear it up and do it over again. But monumental sums of money tend to make monumental bombs and then you're stuck with them."

There are those, even among the film buffs, who think some of their opinionated peers make like D. W. Griffith but have nothing to show for it but their big mouths.

"The era of silent films is past," wrote one student, "but the era of silent film-makers is yet to come."

Even Joe Losey, who was for the most part enthusiastic about his experience at Dartmouth, gave me this description of his class: "Some are first-rate thinkers, some seem to be creative, many serious, others are already full of shit to the brim."

How could it be otherwise? The character of those attracted to movie-making is not apt to change overnight and its always been dubious. But I think Don Siegel gave the most hopeful answer when asked what it would take to change the industry.

"You're the guys who are going to change it," he said. "Remember, when I started out there weren't any groups like this. I never was able to get anywhere near a director. The whole medium was surrounded with mystery and the only way you could learn anything was by experience — which isn't bad, but slow and painful, and in a commercial environment, corrupting. There weren't books on film-making, there weren't instructors, there weren't people who were dedicated. So it's going to change. You guys are going to come up and make fine movies without all the phoney business that we have to go through at the studios. Look at what happened with Easy Rider! One film and Hopper has a contract that gives him full control."

The fact is, however, that Hopper hung around the studios for 15 years before he got his chance. And there are students who, unless their parents stake them to the necessary film and equipment, will hang around the campus hopelessly waiting for their first experiments with a camera.

In making suggestions for the future of films at Dartmouth, Joe Losey said, "The best way to learn is by actually doing. Facilities here for production are limited and inadequate and should not only be increased but a substantial sum of money should be regularly made available for the production of films."

Peter Smith, General Administrator of Hopkins Center (which should eventually become the locus for creative work in movies as it is for the other creative arts), put the issue even more pointedly in a discussion of a future film curriculum: "It would be very sad if we couldn't carry it to the point as you do in music, art, or literature where the student is ultimately faced with the question of what he would have to say in his art if he had a chance to say it. Unless we can bring him to that point, I think we're selling him short, selling ourselves short, selling the art short."

The current film program at Dartmouth doesn't mean to sell anyone short but it has its limitations. Blair Watson, as the benevolent and overworked czar of Dartmouth College Films, squeezes the maximum usefulness out of his equipment for the benefit of students interested in movie-making. And films — some of high quality — will continue to be made, whether the facilities and curriculum are augmented or not.

The question is — as Provost Leonard Rieser has asked with a completely open mind - "Should we at this time rev up the whole operation?" This fragmented report of student interest and opinion is meant to suggest that we should.

Author Maurice Rapf '35 (I) with BuckHenry Zuckerman '52, screen writer forthe highly successful "The Graduate."

Director Joseph Losey '29, who gave acourse at Dartmouth last term, shownat the film office in Fairbanks Hall.

Director Don Siegel (Riot in Cell Block 11) talking with Dartmouth students in a winter-term seminar.

Maurice Rapf with writer Dave Walker during the shooting of a Family CircleMagazine film designed to promote jobs for Negroes in supermarkets.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA CHANCE FOR THE PENTAGON TO HELP SOLVE SOME DOMESTIC AS WELL AS MILITARY PROBLEMS

May 1970 By GERALD G. GARBACZ '58 -

Feature

FeatureProject IMPRESS

May 1970 By JOANNA STERNICK -

Feature

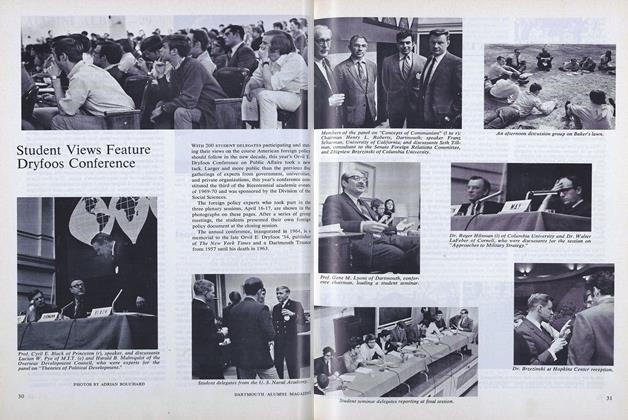

FeatureStudent Views Feature Dryfoos Conference

May 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

May 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1970 By HAROLD F. BRA MAN, WILLIAM M. ALLEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Conference

November 1956 -

Feature

FeatureNature Conditions Architecture

June 1954 By EDGAR H. HUNTER JR. '38 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYAvenging Angel

NovembeR | decembeR By ERIC SMILLIE ’02 -

Cover Story

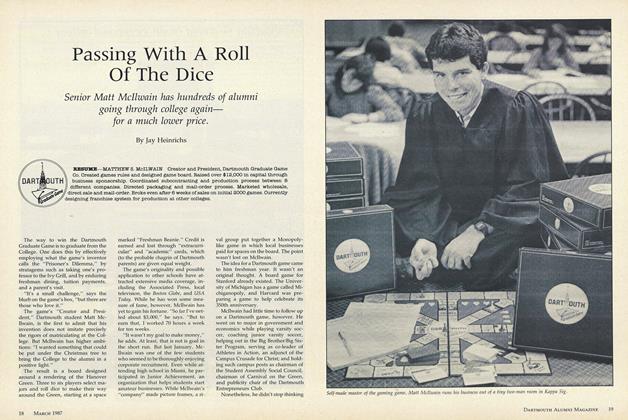

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

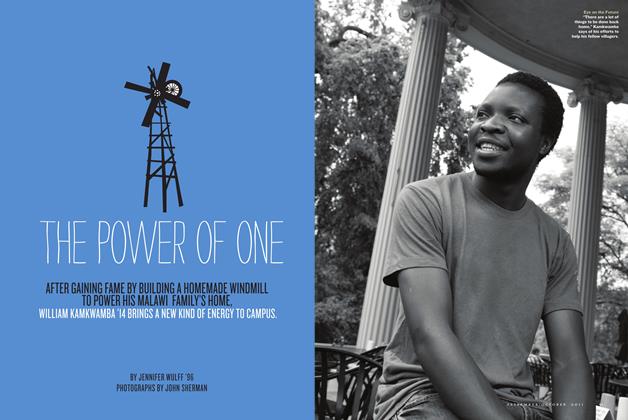

Cover StoryThe Power of One

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Undying

JULY 1970 By SHERMAN ADAMS '20