President Kemeny's Convocation Address Opening the 201st Year of the College

Last spring a new spirit was evident at Dartmouth. We came through an emotionally charged atmo-as a united community. We debated some of the most difficult issues facing the nation and the world, yet we came out of it not more divided but more united. The key question I must ask you now, the challenge I must place before you, is whether we can enter the new year with the same sense of unity, the same willingness to debate difficult issues, and whether we will come out of this year still that united community which meant so much to all of us.

I have to remind you that we have unfinished business. Last March in my inauguration I asked that the coming year be dedicated to a year of soul-searching in which we would examine the very foundations of the educational system at Dartmouth College. We must return to this task; we must ask and debate difficult questions. We are very likely to disagree and yet, somehow, out of disagreement I hope consensus and a great new educational system will come.

During the past months I received many suggestions and the summer afforded me an opportunity to do much thinking about them. I would like to take this opportunity to share with you some of my thoughts, and to call to your attention at least a few of the major opportunities that are presented to us for the coming year.

As I said in March, I see the fundamental educational role of the institution as that of training the future leaders who can solve the problems of society. As I meet the Class of 1974, I cannot help asking the question of just what these problems will be four years hence. Since you, the freshmen, are training yourselves for a career which is at least four years in the future, we must ask ourselves: What are the problems that you probably will have to face?

It is very easy to answer that the problem will be the war in Indochina, but I cannot believe that. In spite of the tremendous amount of bitterness in the country today, in spite of the fact that we are divided on many details about actions in the immediate future, there is a fundamental consensus that we must disengage from this war. The President of the United States has pledged that he will disengage us from this war and he staked his future on that fact, therefore I do believe that by 1974, and probably much before then, this issue will be closed.

When one listens to the news, particularly from the Middle East, one is always faced with the possibility of international catastrophe. But it is not possible to make reasonable plans for a future continually counting on a catastrophe that could destroy the world. And therefore, although I am mindful that such a catastrophe could occur, I must act on a fundamental faith, that no matter how close mankind seems to come year after year to catastrophe, somehow we will continue to escape.

This leads me to believe that the fundamental issues four years hence will be issues within our own nation.

America the Beautiful, which we sang together earlier in this Convocation ceremony, is one of the loveliest songs I know. It expresses a dream, a dream that I believe can be realized. It speaks of "beautiful for spacious skies," of "alabaster cities, undimmed by human tears," of "brother- hood from sea to shining sea." These are wonderful goals for America and I for one believe that they can be achieved. And therefore I believe that it is fundamental that we have re-dedication of the goals of this nation for the achievement of that dream, so that we may wipe out racial prejudice, that we may turn around the decay of the cities and build them into "alabaster cities undimmed by human tears," and that we may wipe out pollution, wipe out poverty and illness, and solve all the tremendous problems that face modern technological society.

Today I am hopeful that we are close to such a national commitment. When I read a Gallup Poll showing that Americans feel very strongly that we should decrease military spending and apply these funds to the fundamental problems of society, when I see the United States Senate putting through a very tough clean air bill with not one dissenting vote, when I look at the lowest common denominator of our civilization—commercial television—and see for the first time in the long, sad history of television serious programs discussing with absolute frankness racial problems, problems of drugs, problems of the city, when I watch those commercials on which large corporations spend millions of dollars and find that a tremendous number of them are suddenly talking about problems of pollution, I must believe that all the rhetoric, all the argument, has paid off and we are coming very close to a national commitment. I must believe that when we are able to disengage from a very costly and tragic war we will make a national commitment to apply the same energy and the same resources to solving the problems of society, I therefore believe that by 1974 the problem will not be one of commitment.

I would like to go on to say that by 1974 we not only will have a commitment to solve these problems, but we will either have solved them or will have made a major start on solving them. But I am afraid that I don't believe this. No matter how early we make this, commitment, I can't believe the tremendous problems of society can be cured in a very short period of time. They are very hard, they are tremendously complex, they are often over-simplified by those who talk about them, and I think it will take a new generation with different kinds of training before we seriously make a dent in these problems.

Therefore I believe that when you, the entering freshmen, enter the world as professionals, it will be your job, and of those who come after you, to change from rhetoric to deeds, to be able to carry out the commitment that will have been made by that time, to live in an age in which society will no longer tolerate excuses, will not tolerate self-indulgence, will not tolerate self-pity. It will be a society that will have to have its problems attacked seriously by well-trained professionals, in all the professions, who come up with creative new ideas—not ideas dreamed up in drug-induced dreams where you have the delusion that you can solve all the problems of society, but new ideas that come out of training, out of dedication, and out of understanding of the fundamental problems.

What does this say about the future of education at Dartmouth? In looking at all the suggestions that have come to me, I found that it is sometimes very hard to draw a borderline between two different kinds of suggestions. It is sometimes difficult to decide whether a change is a change in the direction of greater flexibility or simply in the direction of making life easier for students. I happen to believe that greater flexibility is desirable, indeed essential, in this highly complex world. I happen not to favor making life easier for you, because if we made life easier for you in the educational process, you would not be prepared to tackle the tremendously important problems that face you at the other end.

I would like to give you an example of this. Many suggestions I received concerned the requirement of completing a major. There were any number of questions asked as to why completing a major is important in this day and age, why it is relevant. I personally believe that the requirement of the major is important because, unless you come to grips once in your life with one major area that you have mastered on your own, you have missed a fundamental point in the training of your mind. Unless you are capable once in your life of spending months, and indeed years, mastering a large area of human knowledge, you will later in life be unable to tackle the complex problems that face the world. Therefore I can only view a move to abolish the major as one that would water down education.

On the other hand, I welcomed the suggestion that came out of two faculty committees and that was voted by the faculty last spring—to give new flexibility to the design of majors. The new "special major" allows any student—if a traditional major does not fit his specific needs—to propose his own way of concentrating, and if a small group of faculty members feels that this is a reasonable proposal, the student may have his own specially made major. This to me is a tremendously ingenious idea that in no way waters down the major requirement and clearly adds a new degree of flexibility for the future.

Last April I asked members of the faculty to talk to their students in class about the relationship between faculty and students. I received many interesting answers. If I had to summarize them, I would say that the overall relationship between faculty and students inside the classroom is excellent at Dartmouth, probably as good as at any institution. The major complaint, however, was lack of opportunity for informal meetings between faculty and students outside the classroom. We have discussed a number of possibilities for providing such opportunities. Some of the experiments we will try this year are addressed specifically to meeting this need.

The first of these is the new Choate Road residence experiment, of which you will hear a great deal more, which may present a pattern for the future for a new type of living arrangement and provide extracurricular contacts between faculty and students. I must mention the new Cutter Hall experiment as a significant step in the same direction. I am also looking forward this week to the dedication of the new Center for Foreign Students. All these explore new patterns and new organizations intended to provide flexibility.

A completely different kind of approach is the possibility of two first-rate liberal arts institutions forming a partnership in which either could take advantage of the offerings of the other institution, without in any way giving up its individual identity. Last spring we started informal explorations of such an idea with Wellesley College. These continued over the summer. There were meetings between the two administrations and two exchanges between faculty groups. The whole plan is still in the talking stage and is open for everyone's discussion. I must say that after a period of looking into this I am quite excited about the possibility, because it seems to me to open up a number of new avenues, to give more flexibility, to give more freedom, without in any way encroaching on anyone's particular plans. If you don't like it, you don't have to participate in it—it is as simple as that!

These two institutions have great similarities and yet are quite different—for example, in the type of community in which they are located. If these institutions could cooperate in this manner on a purely voluntary basis, it might set an example for many national experiments and might, indeed, be very important for the future of Dartmouth College.

We have acted on a number of recommendations from the Committee on Equal Opportunity. We are, of course, continuing our commitment to the Black Studies Program. We have made considerable progress in the appointment of a significant number of new faculty members and officers who will be helpful in this program. We are continuing our commitment to the admission of a number of special groups of students, notably blacks. We also initiated a rededication to the original purpose of Dartmouth College with the admission of the first significant group of American Indians in nearly 200 years. And finally, to back up our commitment to the equal opportunity program, we are trying out a largescale experiment recommended by the Committee, the so-called Structured Freshmen Year, which is a new idea in bridging the gap between where the poorer high schools may have left our students and where we expect them to be by the beginning of their sophomore year. I think we can look forward to great progress in this whole program.

Next I must turn to the work of the Trustees' Study Committee. As you know, this Committee has now completed a year of deliberation. They have looked into the fundamental question of the education of women at Dartmouth College and they have tried to ascertain the opinions of all constituencies in the Dartmouth community, opinions that were distributed to all of you on campus and to all living alumni of the institution. The collection of this information represented an enormous amount of work and it laid the groundwork for the committee's preliminary report, the essence of which was to recommend to the Trustees that a significant number of women be educated by the College.

This leaves two crucial questions: one, the question of how—of which of many different models of coeducation they should recommend to the Trustees; and secondly, the very basic question of what the financial implications of a given pattern of coeducation may be. I am quite certain that coeducation will be one of the major topics of discussion during this year and I personally hope that this may be a year of decision.

In this, and in all other controversial issues that come up, my administration will continue to share all relevant information with members of the Dartmouth community.

As a new experiment, at a meeting of the General Faculty next week I am going to make a completely free and open presentation of the financial situation of Dartmouth College and answer any questions about this that they may wish to ask. Incidentally, members of the student press have been invited to that meeting to insure complete coverage on the entire campus.

The Committee on Organization and Policy, one of the key committees of the Faculty, has in front of it some extremely pressing business. I am afraid that I made life more difficult for them by asking them to undertake a special task for me. During my first six months as President I found a great need for something that was missing in the Structure of the College. There are a large number of complaints that come up in a given year. Sometimes they are due to lack of information; indeed I found during Freshman Week that the rumor-mill was working overtime very early this year. Sometimes they are due to the fact that the person complaining simply does not know where to address a complaint. Sometimes the complaint is not answered. Sometimes it is justified and sometimes it is not.

It is clear to me that the President must bear ultimate responsibility; if anything is wrong in the institution he cannot ignore a complaint. But it is equally clear to me that he cannot be the first station for all complaints to come to. On the one hand, if that happened he would never have time for anything else, and on the other hand, if all inquiries come directly from the President there is the danger of an over-reaction and panic which is not good for the institution. I have therefore asked the COP to work out a system for complaints—whether it be a single man, usually called an ombudsman, or some other arrangement—and to make a recommendation this fall, so that I may implement a regular system by which complaints will be heard, will be looked into, so that if a complaint is legitimate, something will be done about it.

I have left for last the Committee on Educational Planning because the essence of our debate, as far as the future of Dartmouth is concerned, must be education. The Committee on Educational Planning is charged by the institution with recommending new plans for the education of Dartmouth students. They have received a tremendous number of suggestions, as I learned when I met with the chairman of the committee. They have many interesting proposals before them and I am quite certain that they would be responsive to any new proposals if they are well thought out and well documented.

I would like to take this opportunity to make a proposal to the Committee on Educational Planning. I see an opportunity for combining within one plan a great many suggestions. I have heard testimony from many of you that the time you spend in a project off the campus is often one of your most valuable experiences. I have also heard that sometimes you are frustrated by the fact that the experience is shorter than you would like it to be. There are a number of problems concerning the use of the summer term; Hanover's magnificent summer weather presents an incredible opportunity for the institution, but we have never been able to take advantage of it. A number of studies, both as to the content of the summer term and the content of programs to be offered by Hopkins Center in the summer, indicate that the only possible solution, the only really attractive solution, is to give parity to the summer term, to make it a term predominantly for Dartmouth students, which would be highly attractive—at least as attractive as the other terms-—so that a significant number of Dartmouth men will wish to attend.

Finally, we are considering plans that may lead to an expansion of the student body. This presents two kinds of problems. There is the obvious problem of the necessity of building new and expensive buildings. But there is also the problem that many of you believe—as I do—that the smallness of Dartmouth is one of its great assets. An undue increase in the number of students on campus might change the character of the institution.

I have therefore tried to put together ideas from a variety of different plans to accomplish all these goals. I would like to propose that the graduation requirement of Dartmouth College be changed: Instead of a twelve-term graduation requirement, the requirement should be eleven terms and the completion of a significant project away from the campus,

By "significant project" I have in mind something that would typically require more than three months—it could be a semester or longer at another institution, a semester or two terms of foreign study, any period from four to nine months spent in the ghettos, an internship in Washington, or a major employment opportunity with direct relation to career aspirations. I hope that the rules would be written flexibly.

I have laid before the Chairman of the CEP a plan under which all these things could, be achieved together. The summer term may become one of the most attractive terms of the academic year. We may again be able to take advantage of the full potential of Hopkins Center. We may achieve new flexibility for planning the educational process. And, above all, in such a way we may add to your education at Dartmouth an important new dimension that could significantly affect your entire life.

I have spoken of many opportunities for the coming year. Men of Dartmouth, we are facing a new year, our 201st year. Together we are about to write a page in the history of the College. May it be a page that future generations will be proud to read!

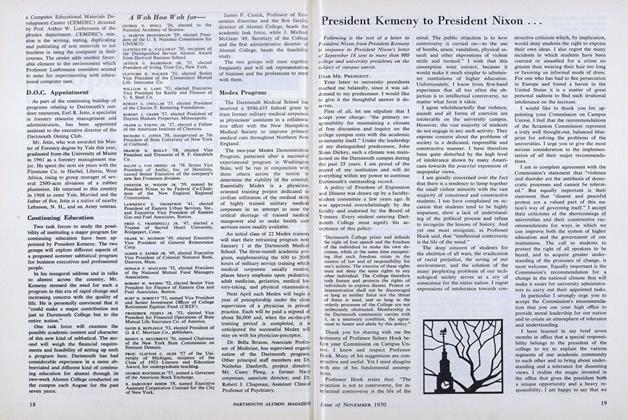

President Kemeny responds to the rousing applause of studentsand faculty as he began his address on September 24.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is a Conservative?

November 1970 By NORMAN LAZARE '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

November 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Article

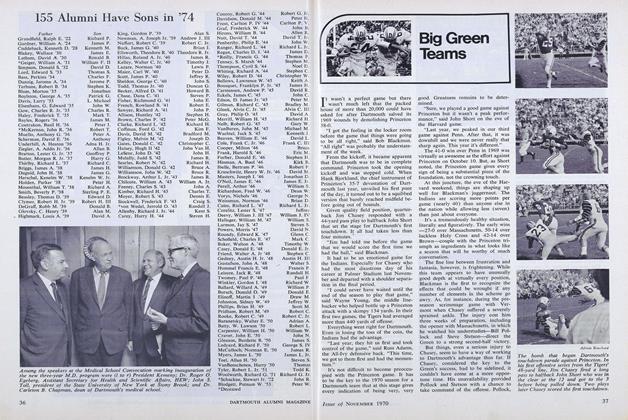

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe ROTC Decision: An Explanation

November 1970 By ARTHUR LUEHRMANN -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

November 1970 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

NOV. 1977 -

Feature

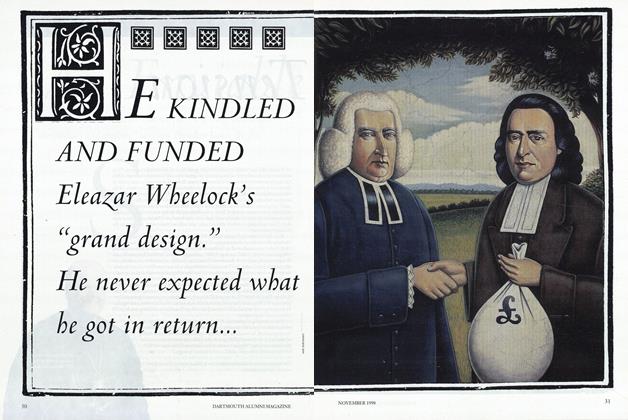

FeatureThe Betrayal Of Samson Occom

NOVEMBER 1998 By Bernd Peyer -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

OCTOBER 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

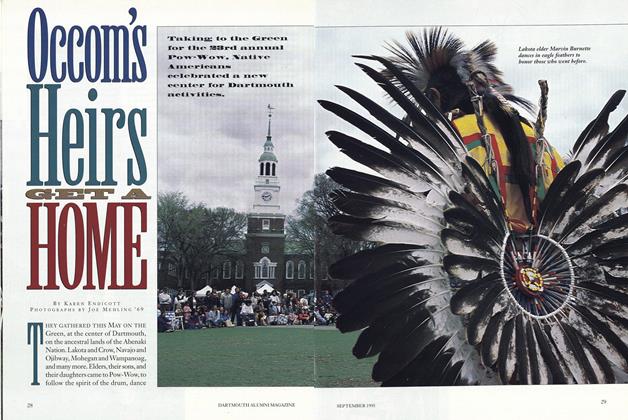

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

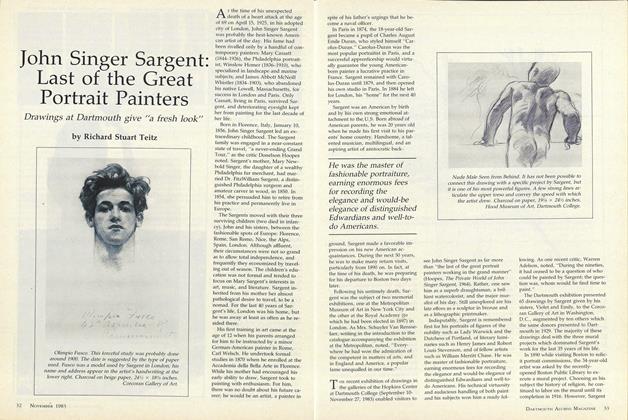

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz