It wasn't a perfect game but there wasn't much left that the packed house of more than 20,000 could have asked for after Dartmouth salved its 1969 wounds by demolishing Princeton 38-0.

"I got the feeling in the locker room before the game that things were going to be all right," said Bob Blackman. "All right" was probably the understatement of the week.

From the kickoff, it became apparent that Dartmouth was to be in complete command. Princeton took the opening kickoff and was stopped cold. When Hank Bjorklund, the chief instrument of Princeton's 35-7 devastation of Dartmouth last year, unveiled his first punt of the day, it turned out to be a squibbed version that barely reached midfield before going out of bounds.

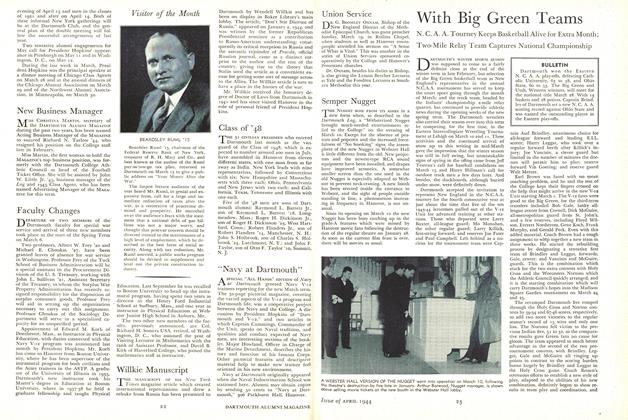

Given quality field position, quarterback Jim Chasey responded with a 44-yard pass play to halfback John Short that set the stage for Dartmouth's first touchdown. It all had taken less than four minutes.

"Jim had told me before the game that we would score the first time we had the ball," said Blackman.

It had to be an emotional game for the Indians. Especially for Chasey who had the most disastrous day of his career at Palmer Stadium last November and departed with a shoulder separation in the final period.

"I could never have waited until the end of the season to play that game," said Wayne Young, the middle linebacker who helped bottle up a Princeton attack with a skimpy 134 yards. In their first two games, the Tigers had averaged more than 440 yards of offense.

Everything went right for Dartmouth. Even in losing the toss of the coin, the Indians had the advantage.

"Last year, they hit us first and took control of the game," said Russ Adams, the All-Ivy defensive back. "This time, we got to them first and had the momentum."

It's not difficult to become preoccupied with the Princeton game. It has to be the key to the 1970 season for a Dartmouth team that at this stage gives every indication of being very, very good. Greatness remains to be determined.

"Sure, we played a good game against Princeton but it wasn't a peak performance," said John Short on the eve of the Harvard game.

"Last year, we peaked in our third game against Penn. After that, it was downhill and we were never really that sharp again. This year it's different."

The 41-0 win over Penn in 1969 was virtually as awesome as the effort against Princeton on October 10. But, as Short noted, the Princeton game gives every sign of being a substantial piece of the foundation, not the crowning touch.

At this juncture, the eve of the Harvard weekend, things are shaping up well for Blackman's juggernaut. The Indians are scoring more points per game (nearly 40) than anyone else in the nation while allowing less (seven) than just about everyone.

It's a tremendously healthy situation, literally and figuratively. The early wins —27-0 over Massachusetts, 50-14 over luckless Holy Cross and 42-14 over Brown—couple with the Princeton triumph as ingredients in what looks like a season that will be worthy of much conversation.

The fine line between frustration and fantasia, however, is frightening. While this team appears to have unusually good depth at virtually every position, Blackman is the first to recognize the effects that could be wrought if any number of elements in the scheme go awry. As, for instance, during the preseason scrimmage game with Vermont when Chasey suffered a severely sprained ankle. The injury cost him three weeks of preparation, including the opener with Massachusetts, in which he watched his understudies—Bill Pollock and Steve Stetson—direct the Green to a strong second-half victory.

But things, even a serious injury to Chasey, seem to have a way of working to Dartmouth's advantage thus far. If Chasey, considered the key to the Green's success, had to be sidelined, it couldn't have come at a more opportune time. His unavailability provided Pollock and Stetson with a chance to take command of the offense. Pollock, particularly, has progressed beyond the wildest dream.

The junior from Nacogdoches, Texas, responded superbly to every call from Blackman. He has played with confidence, poise and strength, and in four games completed over 73 per cent of his pass attempts—"a performance that would satisfy even the best professional," said Blackman.

Chasey in the meantime is hitting better than 60 per cent, but the interesting fact early in the Ivy League campaign is that while Dartmouth was leading every department in team offensive statistics, there literally was no one with the exception of punter Jay Bennett who ranked anywhere near the top in the individual stats.

The answer to that is one word: balance. The burden on offense has been well distributed among Chasey, Short, and their backfield mates, halfback Brendan O'Neill and fullback Stu Simms, plus a pair of fine ends—230-pound Darrel Gavle and Bob Brown, the fleet split receiver.

"When the offense is going well and controlling the ball, the defense can be well rested," said Blackman. "And, if the defense is doing its job, the offense will usually get the ball in good position to take advantage of the situation."

And so it goes. Against Massachusetts, the Indians were pitted in a scoreless tie well into the third period when the defense made the break. It came on a blocked punt by Young's understudy, junior Jim Macko. The big play gave Dartmouth the ball at the UMass 14 and in two plays Stetson produced a touchdown.

Within minutes, Tim Copper (a story in himself this season) added to the demise of UMass by returning a punt 73 yards for a touchdown. These two plays by Macko and Copper took the wind out of the Redmen and Dartmouth coasted to victory.

A week later at Worcester, Chasey made his first appearance of the season. "We wanted Jim to play because he hadn't seen a minute of action since the Princeton game last fall," said Blackman.

"But," continued the winningest coach in Ivy League history, "we hoped that we could score early and not have to keep him in the lineup for more than one period."

Which is what developed. Chasey completed his first six passes in the game and led the Indians to a quick touchdown.

When the defense again gave nothing in return, Holy Cross had to punt. The ball went to Short who handed to Copper on a reverse that these two should have patented. Copper spurted up the right sideline and ran 56 yards.

He appeared to cross the goal as he was tackled but the ball was placed on the one-yard line. In two plays, Simms had his second touchdown of the day, Chasey retired from the combat, and Pollock took over to continue the mauling of the Crusaders.

For these first two games, though, it seemed that Dartmouth's offensive line hadn't really found itself. They were simply saving it for Princeton. As was the defense.

There was never a better demonstration of ball control than Dartmouth displayed against the Tigers. The Indians had 88 chances to move the ball (Princeton had 53). The Tigers never came closer than Dartmouth's 24-yard line to producing a score.

The Indians collected 415 yards of offense while Princeton, which had averaged over 445 yards against Rutgers and Columbia earlier, had its lowest total in years. Bjorklund, who scored three times in the 1969 meeting, was held to 28 yards in 18 carries.

Chasey's first touchdown took some of the wind out of the Tigers and Copper completely deflated them in the first minute of the second period when he took the first punt that Bjorklund didn't kick out of bounds and made the most of great blocks by Barry Brink, Tim Risley, and Bill Skibitsky to scamper 64 yards down the home side of the field for another touchdown.

Before it was over, Short, Simms, and Mike Roberts, the reserve fullback who is averaging six yards every time he carries the ball, had scored.

It was an inspiring performance in every respect. If there was a frustrated Dartmouth player it was Bob Peters, the co-captain and left tackle who had to sit it out with a strained knee. His replacement,, sophomore Dan Bierwagen, was ready for action and played an exceptional game.

The same held for Jim Wallace, the smallest guard (5-6, 190 pounds) in the Ivy League, who played beside Bierwagen and left Princeton's defenders helpless.

The Brown game showed what happens when Dartmouth is given the benefit of someone's mistakes.

Coming on the heels of the strong performance against Princeton, Brown wasn't a team to be taken.lightly—even if the Bruins had not been able to defeat Dartmouth in the last 14 tries.

"Sure, we're not going into this game with the same emotions as we had for Princeton," said Short, "but we know what can happen if we make mistakes."

So Dartmouth didn't make mistakes. Brown did. The Bruins fumbled the first time they had the ball. In five plays, Chasey moved the Green 30 yards and passed the final 12 to Gavle.

Brown then produced a poor punt and Dartmouth again was only 35 yards away. Six more plays, 14-0.

Then it was Young's turn. The junior linebacker from Tarrytown, N. Y., speared a Brown pass in the right flat and had 32 unopposed yards to cover for his first touchdown.

About the only thing that didn't occur was another long run by Copper. It was the only disappointment of the day for Dartmouth fans.

The win over Brown was Blackman's 99th since coming to Dartmouth in 1955. As we write, it seems unlikely that he'll have to wait long for the 100 th.

It would take far too many lines to relate the position-by-position strength that this team has generated. The best illustrations, though, are the veteran center, Mark Stevenson; defensive halfback Jack Manning (who has proven a more than capable successor to departed All-East defender Joe Adams), and Murry Bowden, the spirited defensive rover back.

Perhaps in Bowden lies the secret to Dartmouth's 1970 team. The senior from Texas is a classic example of the contemporary undergraduate—concerned with campus issues, intensely aware of the changes being wrought in society and, still, a competitor who plays football exceptionally well, primarily because he simply likes the game. His performance on the field is like nothing you ever saw, too.

He and Bob Peters are proving themselves to be exceptional leaders of what looks like an exceptional team.

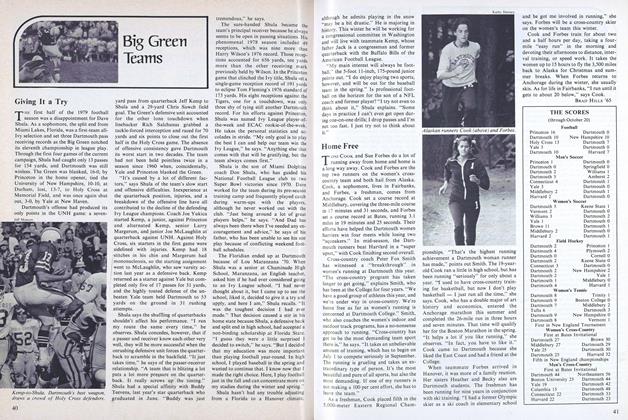

The bomb that began Dartmouth'stouchdown parade against Princeton. Inhis first offensive series from the Tigers'48-yard line, Jim Chasey fired a longpass to halfback John Short who was inthe clear at the 12 and got to the 3before being pulled down. Two playslater Chasey scored the first touchdown.

The bomb that began Dartmouth'stouchdown parade against Princeton. Inhis first offensive series from the Tigers'48-yard line, Jim Chasey fired a longpass to halfback John Short who was inthe clear at the 12 and got to the 3before being pulled down. Two playslater Chasey scored the first touchdown.

The bomb that began Dartmouth'stouchdown parade against Princeton. Inhis first offensive series from the Tigers'48-yard line, Jim Chasey fired a longpass to halfback John Short who was inthe clear at the 12 and got to the 3before being pulled down. Two playslater Chasey scored the first touchdown.

The bomb that began Dartmouth'stouchdown parade against Princeton. Inhis first offensive series from the Tigers'48-yard line, Jim Chasey fired a longpass to halfback John Short who was inthe clear at the 12 and got to the 3before being pulled down. Two playslater Chasey scored the first touchdown.

The alert defense that held Princeton to 72 yards rushing is seen in this actionshot of halfback Jack Manning and rover Murry Bow den stopping the runner,with linebacker Wayne Young (56), safety Willie Bogan (43), linebacker BillMunich (66), tackle Barry Brink (75) and end Fred Radke (82) ready to help.

Punt return specialist Tim Copper (19)turns the corner during his 64-yardtouchdown run against Princeton.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is a Conservative?

November 1970 By NORMAN LAZARE '40 -

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

November 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

November 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Article

ArticleThe ROTC Decision: An Explanation

November 1970 By ARTHUR LUEHRMANN -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

November 1970 By John G. Kemeny