Contemporary Artist

"I paint because I enjoy doing this more than anything else. But also I paint to open people's eyes to a new way of seeing the world and feeling the beauty of it. . . . Because the artist is responsible for his work from beginning to end he bears a special responsibility. He works alone and is in this sense 'free.' Our society needs and will feel the presence of the artist. This is why we must work with love and dedication as hard as we are able."

—Thomas George '40

In a new book recently published by the New York Graphic Society called The Arts on Campus—the Necessityfor Change, Reed College professor Jon Roush asserts that there is a need in this highly rationalized, technological society of ours, to give men the control over their lives and surroundings that artists have over their materials, to make living quite literally a more artistic enterprise. What he is calling for is not more creativity—we are too zealously creative now—but more application of artistic judgment and discipline to questions of proportion and values.

Thomas George, a 1940 graduate of Dartmouth, has achieved a distinguished international reputation as an artist. He is a contemporary painter, one of the most prominent of the avantgarde group, whose wellspring is a deep interest in the organic forms of nature. He is an artist of integrity and vitality and he knows that he "bears a special responsibility." His abstract paintings have been described as expressing the common denominators of life—the images of nature, repeated botanically, anatomically, geologically, sexually... nothing in particular, but everything in general.

To understand Mr. George's progression from realistic studies of natural form to the more personal and universal imagery of abstract painting is to understand something of the artistic approach Mr. Roush is calling for. In a 1966 exhibition in the Hilson Gallery at Deerfield Academy, from which George was graduated in 1936, he attempted to show this progression. Old drawings and studies completed during a period of study in France and Japan were hung with his newest paintings. There were several pen and ink drawings of the olive trees around Renoir's old studio in Cagnes, France. Each of the drawings was painstakingly done and technically flawless. George was fascinated with the convolutions in the trunks of the trees, and taking the next step, he changed to brush, simplified these forms and, finally, narrowed to the base of a single tree. Later he completed scores of black and white studies, using the same forms, but removing them from the trees and letting them stand for themselves. He spent months, and still does, simplifying, attempting to perceive and release the form and pattern from the natural object before he finally moves from paper to canvas The paintings which result from this technique are large, usually black or brown with white, each with a central image, precise and nearly symmetrical They have been likened to ideographs or nature symbols which have captured the essences of the forms through which the natural object progresses in its development.

George has traveled a good part of the world in search of motifs for his painting. He studies trees and rocks and waterfalls much as a botanist or geologist, and sketches directly from nature in summer, then uses this storehouse of information to paint the abstractions in his studio back home. Most important to his development, he considers, were studies done in the Temple Gardens of Kyoto, the drawings referred to earlier which were made in the garden of the Renoir Museum, and now, finally, his Norwegian work, particularly the studies from the Lofoten Islands. These islands are located some 200 miles above the Arctic Circle along the Norwegian west coast. Five years ago he acquired a summer house overlooking the Oslofjord and now spends his summers there and at the Islands which delight him with "the most spectacular landscape I have ever seen." An October one-man show, his twentieth, consisted mainly of work influenced by his Norwegian studies, particularly the Lofoten Islands landscape.

When Tom George attended Dartmouth he was the only art major in his class. The son of cartoonist-writer Rube Goldberg (Tom took the name George shortly after graduating), he had long been at home in the artist's milieu, but was not convinced it was for him. After college he became an apprentice to industrial designer Raymond Loewy until his plans were interrupted by World War 11. He spent four years with the Navy, mostly in photo intelligence work, and upon his release in 1946 faced a career decision. He had been drawing ever since he could remember, had studied art at the Woodstock School and the Art Students' League during vacations, but was still doubtful about painting as a profession. The deciding nudge came from the late Frank Crowninshield, his mentor since childhood, who advised him to go to Slockbridge, Mass., and put in six weeks painting. At the end of the trial, the doubts were gone.

For a few years he studied and painted in New York, winning a few awards and beginning to make a name for himself with his portraits, most notably one of Dr. Frank Boyden, his old headmaster at Deerfield Academy. But since 1949 he has been dividing his time between Europe, Japan, and the United States, working, studying and being exhibited widely in group and one-man shows.

In 1965, while Tom was attending the 25th reunion of his class, Dartmouth held a ten-year retrospective exhibition of his paintings. The show covered the years 1954-1964 and included 22 paintings, as well as selected gouaches and ink drawings. The paint- ings particularly chosen to illustrate his artistic development were Red Painting (1954), Sea Star (1956), Gorge ofToja (1959) and Number Ten (1961).

Public collections exhibiting his work include several museums in New York and Washington, as well as galleries and museums in London, Tokyo, and Lausanne. A number of colleges and universities, including Dartmouth, also own his paintings. They are sold through the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York and the Reid Gallery in London, England.

During one of George's sojourns in the United States in the early 1950's, he made a motor tour of the country and was impressed by the daring and vitality that he saw in industrial construction. His sketches of an eastern oil refinery eventually resulted in a 1954 Korman Gallery exhibition of abstract oils, gouaches, and drawings that attracted high critical praise for their "distillation of refinery construction into its very essence of light and form."

With his wife LaVerne and 9-year-old son Geoffrey, George makes his American home in Princeton, N. J. In its September 30 issue The New YorkTimes ran an illustrated feature on their unusual residence. A former out-building on the estate of railroad magnate Moses Taylor Pyne, the remodeled home has a red-brick tower and a rather cavernous living room 55 feet long by 30 feet wide where George can hang paintings to his heart's content.

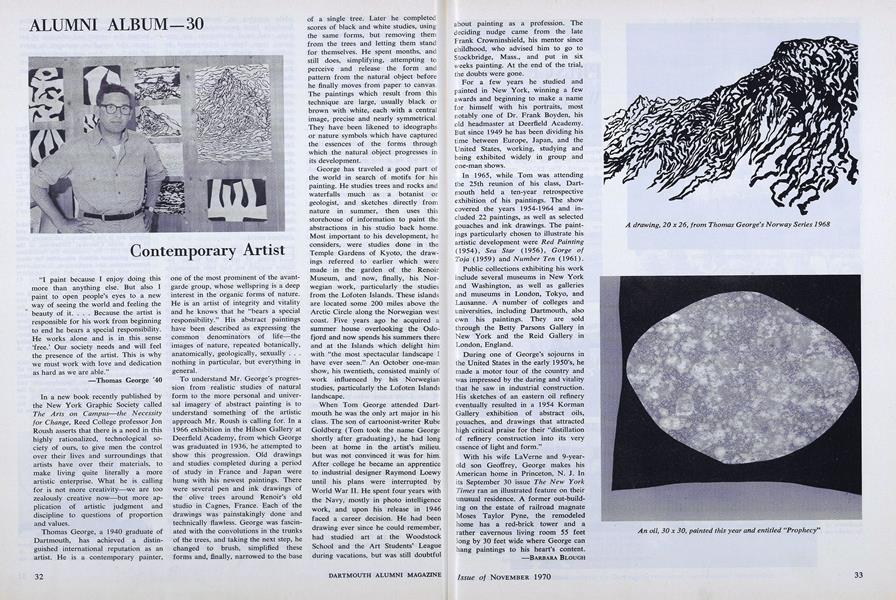

A drawing, 20 x 26, from Thomas George's Norway Series 1968

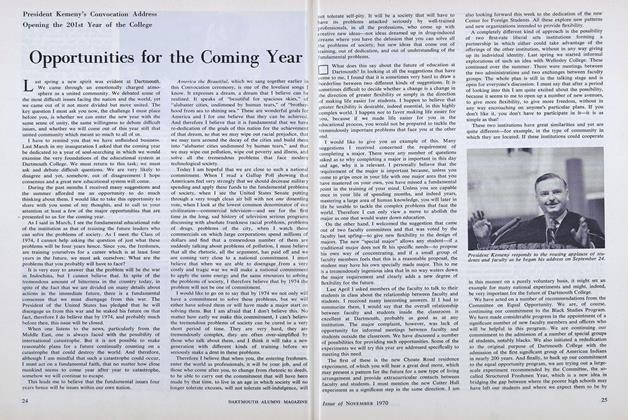

An oil, 30 x 30, painted this year and entitled "Prophecy"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is a Conservative?

November 1970 By NORMAN LAZARE '40 -

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

November 1970 -

Feature

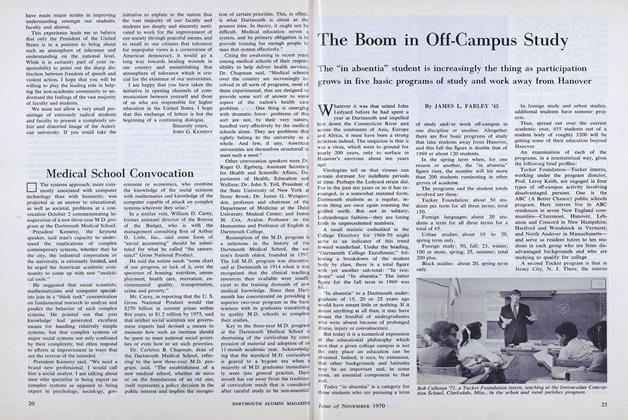

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

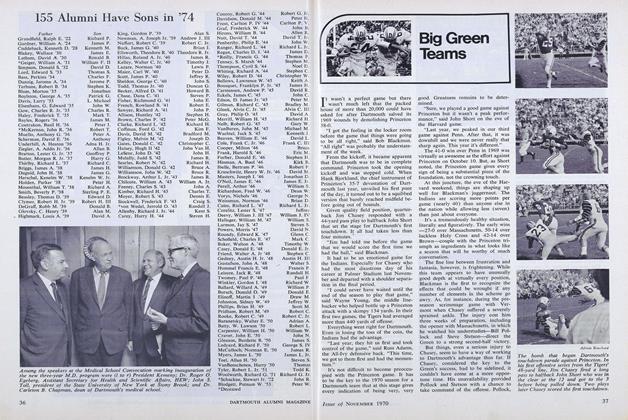

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe ROTC Decision: An Explanation

November 1970 By ARTHUR LUEHRMANN -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

November 1970 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

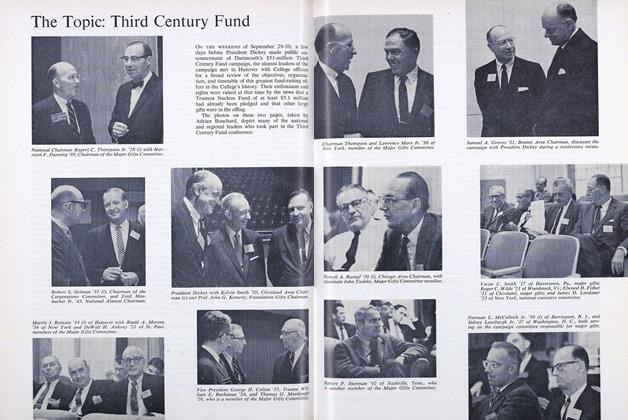

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Cover Story

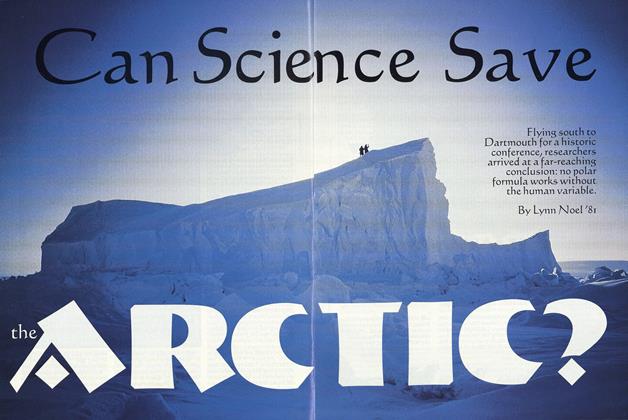

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

DECEMBER 1958 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

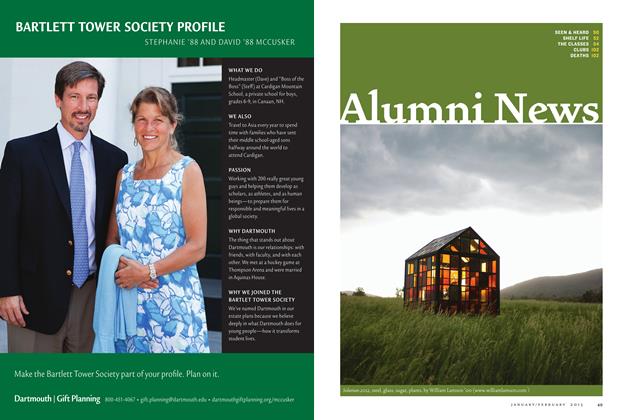

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2013 By William Lamson '00 -

Feature

FeatureFairly Faced

November 1975 By WILLIAM W. COOK