TO THE EDITOR:

I have just finished reading the report of the exhaustive survey of Dartmouth Alumni conducted by Oliver Quayle and Company (Dartmouth Alumni Magazine Supplement, September 1970). Like most of my colleagues I was struck by the overwhelming confidence of alumni in virtually all aspects of the Dartmouth College enterprise. What corporation is as well-approved by its shareholders? What government by its electorate?

Yet there is one issue on which a majority of alumni take exception with the present policy of the College. Forty-nine percent of those polled felt that "the faculty knuckled under to student pressure when it phased out ROTC" and 61% believed that it was wrong to have terminated the ROTC program at Dartmouth. Mr. Quayle's results bear out a similar impression that I received when I was on alumni speaking tours in the wake of last spring's events. For many alumni ROTC appeared to be more on their minds than Cambodia or the Kent State deaths.

I was a faculty member appointed to the committee charged with the task of proposing a policy on ROTC. The question occupied our attention for many man-weeks, and I would like to share with your readers several points which, in my opinion, they ought to weigh very carefully before deciding on the wisdom of our actions.

The first is a trivial point, but alumni appear to be poorly informed about it. It is a common view that a radical fringe group of students coerced the faculty and administration into its final action. Some alumni appear to believe that the ROTC decision was dejure a student decision. But the fact is that the few extremist students were overrun by the vast majority of all Dartmouth students, who wished the ROTC issue to be reopened and who, on a written referendum, urged the faculty to terminate the program. That referendum was the only de jure action by students. It had the effect of calling a faculty meeting to discuss the issue. In my private opinion it was improper of the Executive Committee to grant the right of referendum to students without a general review, such as is going on at present, of the role of students in the governance of the College. But it was a small impropriety. If the faculty had so desired it could have met and adjourned at once. Instead it deliberated for hours on several days and emerged with a solid majority support for the policy which was finally enacted by the Trustees. To complete the history, it was after the faculty vote that the Parkhurst incident occurred. It did involve extremists and their motive was coercive. But the policy set by the faculty was not changed.

My second point is not trivial. It is crucial, and it probably persuaded most faculty members that ROTC ought to move off the college campus. The fact of the matter is that by its very organizational structure the ROTC program necessarily limits the freedom and independence of universities. Once a contract has been signed with the Army, for example, Dartmouth loses all effective control over staffing and content of courses that often amount to 10% of all courses taken for credit by a student here. The officers who teach ROTC courses have in the past been accorded full faculty status, including voting rights. But unlike all other faculty members they are here because they have been sent here to serve the interests of their branch of the military service, not, as in all other cases, because they have been carefully selected by senior faculty members to serve the interests of the College. Similarly, ROTC course content is dictated by current military needs and military philosophy. Intellectual content and harmony with the ideals of liberal learning and free inquiry have never been subject to effective faculty review. The contracts simply do not permit it. In a less central matter, that of student discipline, the line of authority even more clearly bypasses Dartmouth's own channels. The commanding officer has the power in certain cases to request the immediate induction of a student as an enlisted man in his branch of the service. That power was actually used here two years ago.

Perhaps I can bring this situation home to your readers by analogy. For the 49% who, according to Mr. Quayle, are business managers, let them ask themselves how they would respond to having an entire department of their company, say one involved in military production, managed and operated by military officers under orders of superiors in Washington. Let the 9% who are lawyers ask themselves whether they would approve of the assignment to their law firm of several military officers, similarly under orders, to handle litigation involving the military. How would the 5% who are doctors like to have to share a portion of their practice with a military officer, also under orders? If these proposals do not fill your readers with tremendous enthusiasm or even patriotic zeal, then they will understand a very large component of faculty attitudes toward the ROTC program. Teaching and learning are our business, as Mr. Dickey used to remind us, and we like to do it our way and under our control.

To make it clear that the issue in question is one of independence and has nothing to do with the military as such, I shall venture another analogy. Let each of your readers imagine himself to be the president of Dartmouth College and to be confronted by the following proposal from the General Motors Corporation. GM, recognizing the need to recruit bright, well-rounded junior executive officers, will establish a Junior Executive Training Corps program at Dartmouth. Twenty JETC students per year will receive full tuition scholarships and a stipend, and Dartmouth will be paid overhead costs of running the program. The three JETC courses, dealing with the history of mechanized transit, production line management, and union negotiation, must be taken by all JETC students, and Dartmouth must give degree credit for each course. GM will appoint the teaching staff, who must be given faculty status, the senior member to be a full professor. Students who sign JETC contracts at the end of their second year must serve as junior executives at General Motors for at least three years. Finally, any student dropping out of the program may be required to leave Dartmouth at once and go to work on the assembly line in Detroit for two years.

I assume that any of your readers would reject such a proposal, though it offers a carbon copy of our ROTC program. "Why doesn't GM recruit its executives like everybody else?" they might ask. The question is equally applicable to the military services. Yet a majority of Dartmouth alumni would have us accept that same proposal when it comes not from General Motors but from the Department of Defense. Why is that?

The answer brings me to my third and final point. Apparently most alumni feel that the inconvenience and loss of control to be suffered by Dartmouth is more than made up for by our service to our government in a time of need. I have heard this sentiment myself a number of times and I can testify that most of my colleagues agree that in times of threat to national security, universities must perform extraordinary functions. Are these such times? Is the Indochina war similar to World War II or even Korea? Surely not. I was only a boy of ten when the U. S. entered World War 11, but I remember the tremendous popular support for the President and for the war. Before Pearl Harbor young men by the hundreds were going to Canada not to avoid war but to train as pilots for the British R. A. F. Later the newspapers carried stories of fathers and sons who enlisted in the Army together. Dozens of popular patriotic motion pictures celebrated our involvement in the war to save the world from tyranny, racism, and militarism. Food rationing, blackouts, and air raid wardens made the "home front" a believable concept.

Nothing remotely like that exists today-no home front, a single, unpopular movie, and little unity between fathers and sons. Instead of sharing the risks and dangers of war it is fairer to say that by supporting our military policy in Indochina, today's fathers, especially those in the positions of leadership held by so many Dartmouth alumni, are delivering their sons to a war which they themselves do not fight in any sense.

I would conclude, therefore, by urging Dartmouth alumni, who according to Mr. Quayle are mostly of an age to have been profoundly influenced by World War 11, to reconsider the ROTC question in the light of today's military situation. I believe that they will find, as I did, that the need to serve our military interests today is not worth the loss of freedom and independence in carrying on our essential business—teaching and learning. Bear in mind that I do not argue that universities need not serve society. Any social institution that ceases to serve society will not last. But the best and unique way that a university can perform its service is precisely by refusing to do what society thinks it wants at the moment. A great university must be a center of independent thought and criticism. In these trying times we here need the understanding and support of those of you who share this conviction.

Mr. Luehrmann is Adjunct Associate Professor of Physics and Director of the ComputerEducational Materials Development Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is a Conservative?

November 1970 By NORMAN LAZARE '40 -

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

November 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

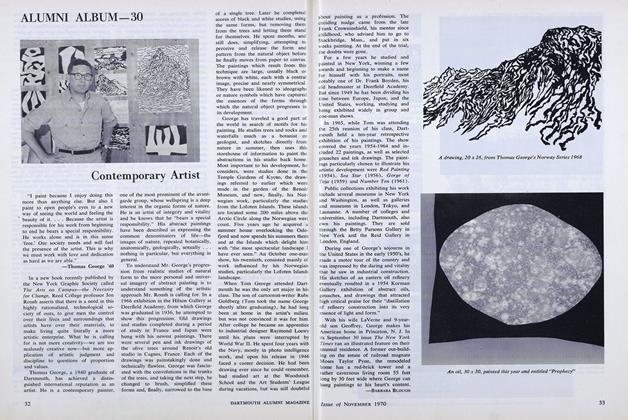

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

November 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Article

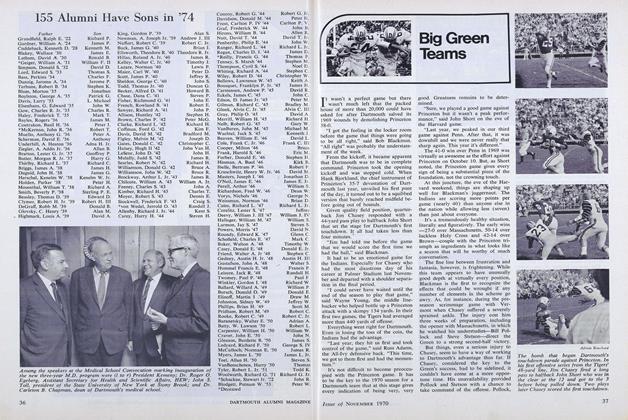

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1970 -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

November 1970 By John G. Kemeny

ARTHUR LUEHRMANN

Article

-

Article

ArticleBOSTON AND NEW YORK CLUBS PUBLISH DIRECTORIES

January, 1923 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Publications

December 1951 -

Article

ArticleTV Committee

January 1953 -

Article

ArticleClub Secretary of the Year

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Article

ArticleSome Thoughts on the Election

February 1961 By ALAN FIELLIN -

Article

ArticleWhere Wheelock's Great Design Began

DECEMBER 1965 By FREDERICK CHASE '05