A rugged outdoor regimen, involving isolation and self-reliance, seeks to fill a void in contemporary education

How do college undergraduates— intelligent, sensitive, and brimming with energy—come to know themselves as individuals in a society that rarely tests them except in the arena of the classroom where theory reigns over practice, thought over action, and criticism over solution?

How do young people—whose primary responsibility since the first grade has been the education of the self yet whose concerns and sympathies by college age seem often to embrace the world—come to understand something of the dynamics of the group prior to entering a thoroughly interdependent society where few individuals work alone?

How do college students cope with the free-floating anxieties that they feel in an era of intense social tension, profound uncertainty, and rapid change, often challenging the values and purposes of the very culture that nurtured them?

Although these questions are not usually asked in quite this way in the rhetoric of the campus today, they are in part behind the chorus of continuing demands for relevance in education.

While virtually all of the educational process is concerned in some degree with such questions, a group of Dartmouth undergraduates and faculty are addressing themselves to answers from an exciting and fresh perspective that takes advantage of the College's special location in the foothills of the White Mountains.

With the start of the winter term next month, they will head into a tract of wilderness owned by Dartmouth on the southeast slope of Mount Moosilauke, 45 miles north of Hanover, to add an uncompromising and vivid relevance to their liberal arts studies and to gain new insights about themselves as individuals and members of society.

They are the vanguard initiating the new Dartmouth Outward Bound Term, fusing a stern wilderness encounter with academic learning. Their "campus" or headquarters will be the forested amphitheater that the Moosilauke Ravine describes on the shoulder of nearly mile-high Mount Moosilauke. There the huge, rambling Ravine Lodge, built of logs felled in the area by Dartmouth students 33 years ago, is being renovated to serve as a base for the Outward Bound headquarters, but for both students and staff tents in the snow will be their home for much of the 10-week term.

In winter, their classroom may also be carved from the snow of the 27,000 wilderness acres of the Second College Grant tucked up near the Canadian border in northeast New Hampshire, while in spring they may shift to whaleboats on the cold, grey Atlantic around Hurricane Island off the coast of Maine. But, in either season, students volunteering for the Outward Bound Term will never be far from direct confrontation in three critical areas: with the natural elements for at least three weeks, with little but most basic necessities; with themselves in a series of situations under stress, and with their peers sharing the experience.

Yet, under the new program, by means of reading assignments, periodic seminars—some out-of-doors but most in the Ravine Lodge—observation and writing, the students will also be immersed regularly in such disciplines as psychology, sociology, education, philosophy, theology, English literature, environmental studies, and archeology, relating experience to concepts and concepts to experience.

The concept of an Outward Bound Term was accepted earlier this year by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences as a valid academic enterprise, the first term-length Outward Bound Program to be accredited at any major institution of higher learning in the country. But, because of the intensively interdisciplinary character of the teaching planned for the term, students successfully completing requirements, will receive the equivalent of full credit for their work by means of a three-course reduction in degree requirements— from 36 to 33. At Dartmouth, which has a three-term system, students usually take three courses per term, or 36 courses over four years.

While this year's Outward Bound Term is new in its details, worked out between the College's Outward Bound staff headed by Willem M. Lange III, and a new faculty advisory staff, the Outward Bound movement opened its first Center at Dartmouth two years ago under the aegis of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation to test the educational potential of the concept.

Proposed 15 years ago by President John Sloan Dickey to "further the moral and spiritual work and influence of the College," the Tucker Foundation since then has provided various program vehicles enabling undergraduates to translate their urgent social concerns into constructive action while also learning. As a result, Dartmouth has become one of the few major institutions of higher learning in the United States to develop a far-reaching program of experiential education carrying degree credits. Under the auspices of the Foundation, for instance, approximately 180 undergraduates each year become teaching interns and work at project sites around the country from Claremont, N. H., to Compton, Calif., and from cities like Chicago and Jersey City to a small community in Mississippi. In all these instances, participating Dartmouth students apply themselves and their learning to distinct social needs, teaching, and helping others.

Dartmouth Outward Bound, in contrast, is concerned with helping students understand themselves and their world and their relationships in it and to sharpen their entire educational experience at Dartmouth. Thus, while providing important personal insights, the encounter with the elements, with themselves and with anxiety is being designed here to reach beyond the self to illuminate their studies across a wide academic spectrum and to demonstrate that an individual conscience "turned on" to life can operate within existing institutions to improve the quality of life in today's society.

The Outward Bound movement, which has some of its roots in William James' philosophical concept of "the moral equivalent of war," actually began in England during World War II as a form of survival training. It was conceived to cut down the tragic toll of young British merchant seamen who, it was noted, then were succumbing more often to the rigors of the North Sea than older more experienced crewmen after their ships were sunk by Nazi submarines.

The program, which trained men to handle themselves in adversity by subjecting them to a series of demanding tests in supervised but seemingly hostile and threatening situations, was so successful that its architect, Dr. Kurt Hahn, an anti-Nazi German educator who had settled in England and founded the Gordounston School, adapted it to civilian needs after the war.

The idea spread rapidly in Britain. To five Outward Bound Schools there were added 15 more in Europe, Africa and Asia, including Australia and New Zealand. In 1962, the first Outward Bound School in the United States was started near Denver. Since then, five other schools have been created—one each in North Carolina, in Oregon, on Hurricane Island off the Maine coast, in California, and in Minnesota, where Alan Hale '61 is director.

All the while, Outward Bound has been evolving from its original survival training mission to meet the imperatives of war and, using nature as the primary protagonist, offers a kind of encounter experience that seeks to teach self-knowledge and confidence, compassion for others, and a sense of the place of man in nature by providing an elemental testing ground largely eliminated by modern society.

In 1968, in its first formal link with an institution of higher learning, Outward Bound chartered a unit at Dartmouth, but called it a Center to distinguish its special educational and experimental purpose from the essentially project-oriented Outward Bound Schools. Already the Dartmouth Outward Bound Center lists more than 300 alumni—about one third of them Dartmouth students. The other two-thirds are undergraduates from other colleges, school teachers and administrators, and secondary-school students for whom Dartmouth students who have just completed the experience serve as assistant teachers as part of their own educational program.

Elsewhere, the regular Outward Bound School course is four weeks long, but at Dartmouth the Outward Bound Term is of ten weeks' duration, divided into four disitnct segments, preceded by a prelude and followed by an epilogue. They are: a reading period prior to the start of the term; three weeks of wilderness encounter; three weeks of intensive study at the Ravine Lodge; three weeks as apprentice instructors on a second Outward Bound mission for secondary-school students; one week of critique and evaluation; and finally an indefinite period to complete a major paper on the total experience.

While the reading lists are subject to change and refinement, books proposed by members of the Outward Bound Term's Faculty Advisory Board range from Paul Tillich's The Courage to Be to the poems of the southern American poet James Dickey, from Hornbein's Everest: the West Ridge to Whyte's Street Corner Society, from Heming-way's Old Man and the Sea to Holt's How Children Fail and Hentoff's OurChildren Are Dying, from Graham Blaine's Youth and the Hazards ofAffluence to Paul Goodman's Growing up Absurd.

After having digested this kind of fare, the Dartmouth students will join an equal number from other schools at the start of the winter term to trek out the Appalachian Trail through the snow and cold 45 miles to Mount Moosilauke. There, for the next three weeks they will live as patrols of eight or ten in pup tents, learning to cope not only with the elements and the environment, but with a host of demanding tests built into the program. These will range from early-morning obstacle course runs before breakfast to learning how to rappel down scary 75-foot cliffs of the Moosilauke Ravine headwall.

Although the activities are closely supervised and controlled, discomfort and a sense of danger are constant companions. Yet, each individual is forced to think beyond himself, since each problem is framed as a group operation, and no crew or patrol or "watch" may move faster or farther than its weakest, most awkward or frightened member. The individuals have to learn to work together to succeed, learning to draw on the varying skills and strengths of each member as they apply, and to support the weaknesses of each member as they surface.

Regularly, during this first three-week phase, which becomes, in effect, an endurance test, faculty on the Outward Bound advisory group will come up to the Ravine area to conduct seminars and hold discussion sessions, with particular emphasis in this period on the faculty from the human relations area such as George Theriault '33, the Lincoln Filene Professor of Human Relations, and John T. Lanzetta, Professor of Psychology, both of whom are specialists in sensitivity training and encounter sessions.

The climactic test of the first phase is entirely individual. Then, each man moves from the camping area to an assigned location in the forest out of sight or sound of anyone else for a three-day solo. With only minimum food and equipment (shelter is usually a snow hole in winter), he is required to sustain himself and, in the process, to confront himself and his values as they have been tested in the Outward Bound encounter. For young persons- and for the mature as well—brought up in a civilization that has almost abolished solitude, the impact is profound.

Yet, from it all, from enduring, from overcoming panic, choking down fear of height, overcoming exhaustion, fighting off the loneliness and panic that can rise from prolonged silence and unyielding cold, extracting humor from moments of misery, helping others and accepting help, most students manage to find reserves of will and strength they did not know they had. From this for most participants comes a sense of self and appreciation of others that is vivid and concentrated. For many young people, the discoveries add an important quality of confidence to egos suffering the uncertainties, even the desperation, of youth as yet uncommitted to career or family in an existential age seemingly bereft of enduring values or stable communities with which to identify.

For participants from other colleges, the solo ends the course, except for a short debriefing and "graduation" rites. But for the Dartmouth students in the Outward Bound Term, completion of phase one is only the beginning.

For the next three weeks, they move into Ravine Lodge for three weeks of intensive study with their faculty advisers for more reading and writing. In addition to Will Lange, director, and Professors Theriault and Lanzetta, they are:

Fred Berthold Jr. '45, Professor of Religion; Donald A. Campbell, Professor of Education; William S. Magee Jr., Assistant Professor of Chemistry and an authority on man's threat to his environment; Robert H. Siegel, Assistant Professor of English; a member of the anthropology department; Joseph Nold, director of the Colorado School of Outward Bound; and Alan Hale, director of the Minnesota Outward Bound School.

In phase three, the Dartmouth Outward Bound students take over as apprentice Outward Bound instructors, or watch officers, for a group of up to 40 secondary-school youngsters, drawn equally from nearby high schools, topflight prep schools, and ghetto storefront academies, who have volunteered to go through the basic three-week Outward Bound experience. Here, in a 24-hour-a-day commitment to their younger charges, they put much of what they've learned about leadership, human behavior, and group dynamics to work. A final fourth phase is a one-week period of debriefing and analysis with the faculty, and the identification and beginning organization of a major paper on some phase of, or observation growing out of, their total Outward Bound Term. Like the reading period prior to the term itself, the actual writing of the paper is expected to spill over into the next term, since inevitably it takes a student at least three or four days to unwind from the tensions of the combined experience.

Students who do exceptionally well in the Outward Bound Term and find it challenging are eligible for an Outward Bound Internship. Under this program, interns spend a ten-week term at a secondary school helping to integrate the Outward Bound experiential concept into the regular school curriculum there, while acting also as teaching assistants, tutors or counselors. Interns successfully completing the internship receive three course credits in Education. Students majoring in behavioral sciences may receive additional credit by designing and carrying out independent research projects investigating the impact of the Outward Bound experience on individuals or as an educational vehicle.

According to faculty members, the Outward Bound Term, as with any novel approach to education, still has "bugs" to be worked out. To Professor Lanzetta, it is a little heavy on the experiential side, and the faculty is working to right the balance and add a larger academic increment. Meanwhile, he stressed that the institution has to be tolerant. "The program is rich in potential. It will grow and get better but it will take some time."

The sense of potential is reinforced by Professor Theriault, who asserted his enthusiasm for the Outward Bound Term because, he said, "I believe strongly that the most effective way to teach is to combine a student's experience, either through natural or contrived situations, with what he's trying to learn." Similarly, Professor Siegel expressed his conviction that "we learn best when we are experiencing new situations, as in Outward Bound. But as important as the immediate learning, experiential and otherwise, is, I'm impressed by how Outward Bound can add meaning, unfelt before, to courses taken earlier, and provide a most valuable fund of experience adding an extra measure of vitality to future courses."

Professor Siegel explained that he became interested in Outward Bound specifically as a result of a paper, actually a short novel, written by one of his students after completing an early Outward Bound program.

"It was a fictional analysis of the self along the lines of Dostoyevsky's Notesfrom the Underground," he said, "and vividly evoked the intensity of an individual's feeling on facing the cold and group and then finding himself in relationship to the group. It was the pressure of the experience that gave the piece its arresting authenticity. Clearly this man's Outward Bound experience drove him to a brilliant depth of introspection that I am sure will have carry-over impact in his future career."

Similarly, at first glance, a lonely snow hole in the forest may seem an incongruous place to study the philosophies of Tillich, Kierkegaard, Camus or Sartre; yet, from the point of view of Professor Berthold, it is entirely appropriate.

Heidigger says anxiety defines the human being, Professor Berthold explained, while existentialism, an important philosophical movement among young people in the West, agrees that anxiety is one of the most distinguishing attitudes of the human being.

"One of man's basic anxieties, of course, is death, with which all other anxieties are related," he said. "Yet young people, almost prevented by our culture from facing primal anxieties, are expressing their anxiety in terms of such intangibles as the sickness they see in society. But such anxieties are hard to grasp and face.

"In one sense, then, Outward Bound lets them face a fearful thing that's real, identifiable, and prove themselves by defeating it. If they do that, then there's something they're certain about. But more significantly, from an academic view, the effort in the Dartmouth Outward Bound Term is to relate this experience of anxiety and encounter to some of the major philosophies that have shaped modern thought. That to me makes it a legitimate part of the liberal arts."

To Will Lange, who has been at the center of the shaping of Dartmouth's Outward Bound Term since joining the Tucker Foundation in 1968 from the Hurricane Island staff, "Outward Bound has long been an exponent of the ineffable, but at Dartmouth, although we respect the elusiveness of the spirit, we have yoked the idea with the traditional disciplines and find that they pull quite well together."

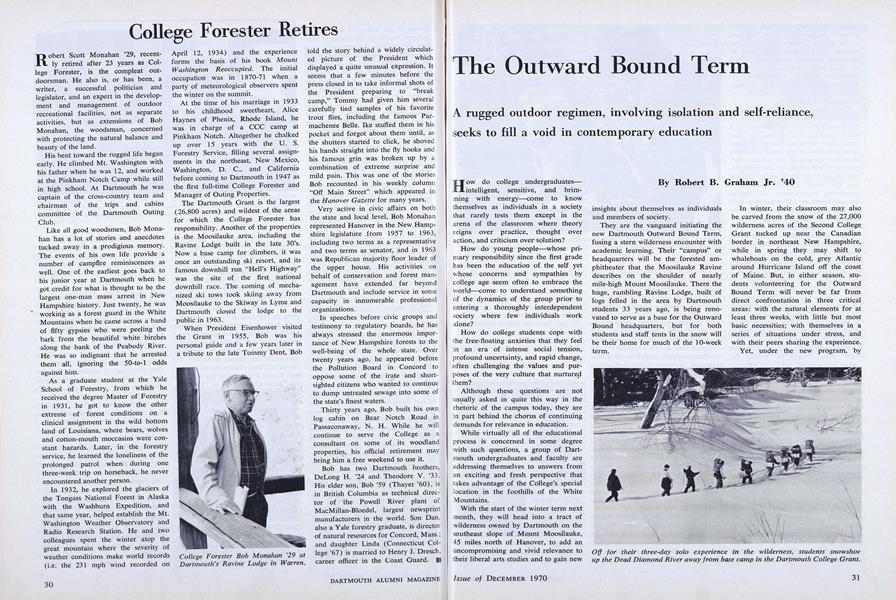

Off for their three-day solo experience in the wilderness, students snowshoeup the Dead Diamond River away from base camp in the Dartmouth College Grant.

Outward Bound staffers Will Lange, Paul Ross, and Bruce MacAdam check maproutes which two student groups will follow on treks into the wilderness.

Jeff Leich '71, who has completed theOuwtard Bound course, gives advice toMatt Miller, a Hanover High student.

Entirely on his own for three days, astudent gets one of life's rarest opportunities for solitude and thinking.

Indoors for the first time in ten days, students wait for "graduation" to begin atthe Grant base camp after a rugged 23-day survival course.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe New Youth Culture

December 1970 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

December 1970 -

Article

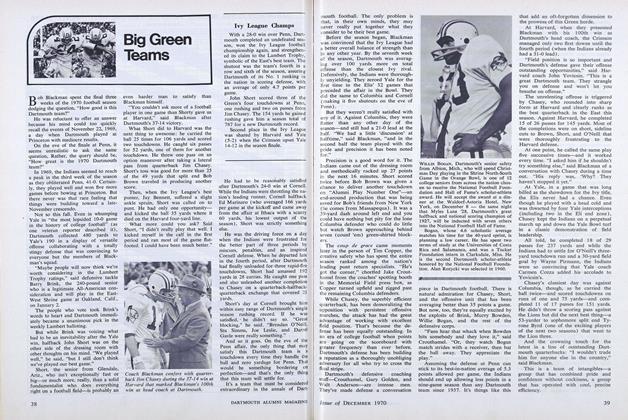

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1970 By CHRISTOPHER CROSBY '71 -

Article

ArticleRamon Guthrie's New Poem

December 1970 By James M. Reid '24

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarming up for 50 years: The yeast of elderly innocence

JUNE 1982 -

Feature

FeatureA Course About Themselves

January 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

NOVEMBER 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44 -

Feature

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74