DARTMOUTH'S CONCERN with environmental problems goes back many years, back much farther than can be said of most colleges and universities now mounting programs in this field. Douglas E. Wade served as College Naturalist from 1943 to 1950 and during that period led students in an action-oriented program not only in the Hanover region but in other parts of the country. Professor Wade wrote the following as a letter to the editor but we prefer to print it as an article, because it gives a fine review of Dartmouth's activities in those early years and also serves as an appropriate supplement to the article about Dartmouth's stepped-up program in environmental studies.

Mr. Wade.,is now Assistant Professor in Outdoor Teacher Education at Northern Illinois University in Oregon, Ill.

PEOPLE involvement is increasing worldwide in the population explosion and correlated environmental problems. This April 22, many groups in educational centers took part in Environmental Teach-ins and related activities. A national office has been established to aid in furnishing helpful information. In view of this, I cannot help looking back a few years in Dartmouth's history when it had, what Robert Frost so aptly labeled, some "Loose-Enders."

As College Naturalist (1943-50), I was one of these L-E's and worked with the Dartmouth Natural History Club (later changed to Dartmouth Ecological Society to give it a broader base) and the Dartmouth Outing Club. The Dartmouth Ecological Society was probably one of the first in colleges in the United States.

Today, student ecological societies are springing up in many colleges and universities and serving as forums to discuss environmental problems and to take action to solve these problems. The Dartmouth Ecological Society was action oriented. Indeed, I feel that Dartmouth, largely through its extracurricular programs, especially those of the Natural History Club (Ecological Society) and the Outing Club, was a forerunner during the late 1930's and through the 1940's in environmental education.

Primarily through extracurricular efforts, a substantial number of students developed feelings and concrete knowledge in the field for many aspects of environment. There was, through student impulses largely, some spin-off into the strictly curricular aspects of the College. Some courses and professors profited by infusions of ideas fed into the system by students and the Naturalist, who had been afield looking firsthandedly at environment. I cannot, in a short space, recite all the things I witnessed happening during the 1930's and 1940's. A few highlights should suffice.

Members of the Dartmouth Ecological Society (D.E.S.) became concerned with mountain tops. They perceived the remarkable sensitivity of sub-tundra areas; they examined slides which in part resulted from conditions set up by poorly-planned trails and ski slopes; they fought against the placement of broadcast towers on certain mountain tops; pointed out the junk-yard conditions which existed on Moosilauke and Mt. Washington; fought against invasion of mountain areas by super-highways and skytop roads; investigated and pointed out to authorities the ecological results of roads along streambanks; investigated pollution and damming on the Connecticut River and pollution on Mink Brook, White River, Great Bay, Isle of Shoals, and instigated the employment of a College Forester early in the term of President Dickey.

D.E.S. undertook in 1949 the execution of a large, colorful ecological display which filled all the main exhibit cases in Baker Library. Parts of the display were hung in the United Nations center at Lake Success, Long Island, during a first international conference on conservation sponsored by UNESCO and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Society cooperated with the Soil Conservation Service in establishing wildlife food and cover test plantings. Some of these may still exist on the old College farm and at the base of Velvet Rocks. Some members spent several weekends at the College Grant planting thousands of spruce seedlings. All D.E.S. members fought forest fires in New Hampshire and Vermont and revisited some of the burns in subsequent years to see what happened when much plant life and organic soil are destroyed.

Members of D.E.S. fashioned nature trails along Mink Brook (continuing the efforts of Dr. Richard Weaver, Dartmouth's first naturalist-in-residence), and put in self-guided trails at Moosilauke and several private camps in New Hampshire and Vermont. Through such work, and the testing of ecological teaching in private camps, the College Naturalist was able to introduce ecology and applied ecology (conservation) to the Northeast Section and the national meetings of the American Camping Association.

Perhaps the finest "camp" payoff came from participation in the founding and direction of the New Hampshire Conservation Camp, from 1945 on. (This camp is still operative under the sponsorship of the Society for Protection of New Hampshire Forests.) Many students served as instructors to the high school boys and girls who attended week-long sessions. Your own Jimmie Schwedland instructed in soils and soil conservation while he was an undergraduate. The camp curriculum was oriented to ecology and environmental problems and this original pattern is apparently still followed.

The office of the Naturalist assisted the late Jim Taylor of the Vermont Chamber of Commerce mount a program to get some enabling legislation passed in Vermont involving trunk lines of sewer systems. Some of the D.E.S. members posted, in an operation dubbed "Back House," a substantial number of public, semi-public, and factory toilets in several towns in Vermont with signs reading: "You are now contributing to the Winooski. What a hell of a way to treat a river."

Environmental education really came alive in a series of spring trips to the Outer Banks of North Carolina by the Ecological Society. Facilities on the National Pea Island Waterfowl Refuge served the groups as headquarters and we went across Oregon Inlet on a ferry. En route down and back we traveled the Skyline Drive, penetrated Dismal Swamp, went into a coal mine, granite quarries, walked the serpentine wall around the home of the president of the University of Virginia, talked with students at the University of Virginia, William and Mary, and Princeton, as well as got acquainted with natives on Ocracoke Island and Hatteras Island. One trip, we spent a day at the research refuge of the Fish and Wildlife Service located near Laurel, Maryland.

Many kinds of studies were engaged in by the students on these Outer Banks trips: we live-trapped and caught by hand one hundred muskrats which were shipped to Bull's Island in South Carolina for a special stocking program; we ran down fifty sick Canada geese at Pea Island and loaded them, four to a bundle in burlap sacks, on a Fish and Wildlife plane which then took them to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Lab at Laurel, Maryland. We examined soils and plants on the refuge at Pea Island and made period reports on birds and mammals sighted. We engaged in both still and motion picture photography. One famous photo taken by Jay Haft '49, showing three nude students strolling down a deserted sweep of beach on Pea Island was stolen and used in the student newspaper to depict revelries on Bermuda Island, but believe me, the softies that cavorted on Bermuda during spring vacation would have had a hard time holding up to the rigors of the D.E.S. Outer Banks trips. A list of students making these Banks trips would reveal alumni of Dartmouth who have become famous in conservation, environmental studies, and environmental education.

In the September 1, 1945, issue of The Moderator: A New England Magazine, a long letter of the College Naturalist was published. The letter, entitled, "Ecological View of DDT," not only dealt with prospective use of DDT in Vermont and condemned its use, but with water pollution, noise pollution, and degradation of New England's landand waterscape. With some rewriting, the letter would be even more timely today. The important thing was that Dartmouth students were being exposed to thinking about environmental problems and the connection of these with human population.

Although the natural inter-relationships of stated course may have been made obscure when hemmed in by walls and departmental "fences," students soon recognized that once they stepped outside in an extracurricular program, these walls and fences did not exist in nature (environment). The extracurricular program built awarenesses with direct, first-hand experiences and was action-oriented. By adding the ingredients of scholarship, the student-product could become a truly effective force.

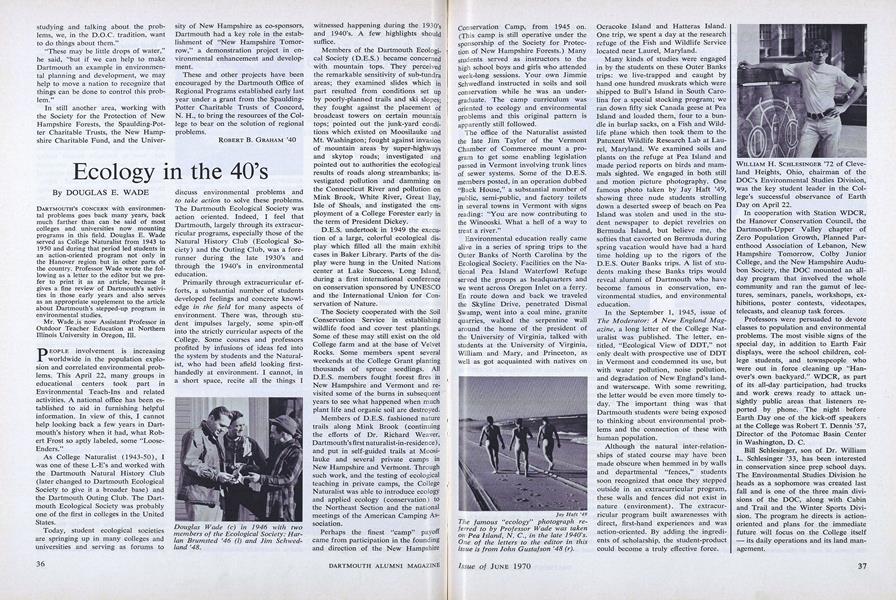

Douglas Wade (c) in 1946 with twomembers of the Ecological Society: Harlan Brumsted '46 (l) and Jim Schwedland '48.

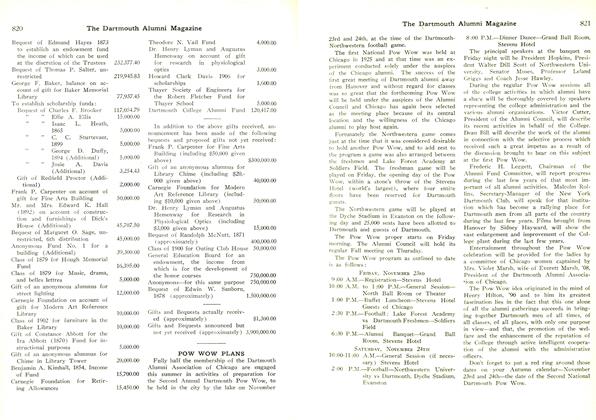

The famous "ecology" photograph referred to by Professor Wade was takenon Pea Island, N. Cin the late 1940's.One of the letters to the editor in thisissue is from John Gustafson '48 (r).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

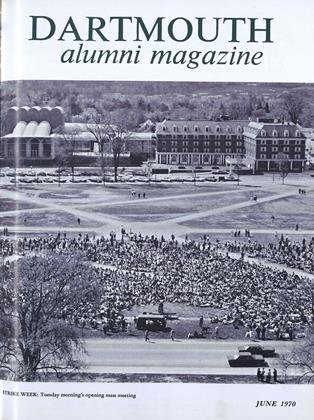

FeatureFor Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike

June 1970 By DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

June 1970 -

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

June 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1970 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT KEMENY'S RADIO TALK

June 1970 -

Article

ArticleWhat the Workshops Meant

June 1970 By GUY DE MALLAC-SAUZIER