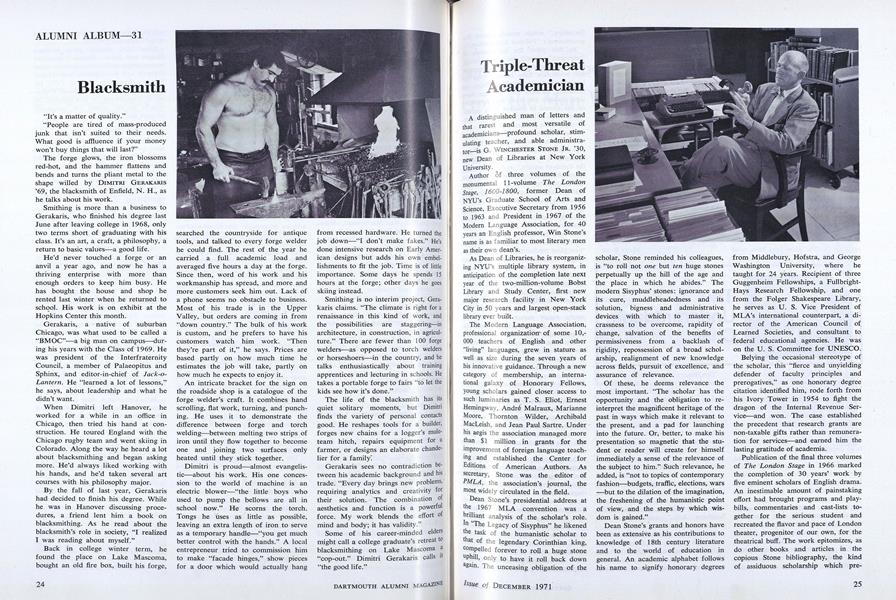

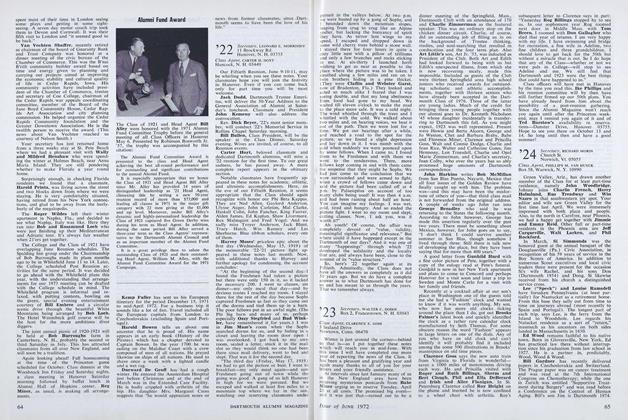

A distinguished man of letters and that rarest and most versatile of academicians—profound scholar, stimulating teacher, and able administrator—is G. WINCHESTER STONE JR. '30, new Dean of Libraries at New York University.

Author of three volumes of the monumental 11-volume The LondonStage, 1600-1800, former Dean of NYU's Graduate School of Arts and Science, Executive Secretary from 1956 to 1963 and President in 1967 of the Modern Language Association, for 40 years an English professor, Win Stone's name is as familiar to most literary men as their own dean's.

As Dean of Libraries, he is reorganizing NYU's multiple library system, in anticipation of the completion late next year of the two-million-volume Bobst Library and Study Center, first new major research facility in New York City in 50 years and largest open-stack library ever built.

The Modern Language Association, professional organization of some 10,000 teachers of English and other "living" languages, grew in stature as well as size during the seven years of his innovative guidance. Through a new category of membership, an interna- tional galaxy of Honorary Fellows, young scholars gained closer access to such luminaries as T. S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, Andre Malraux, Marianne Moore, Thornton Wilder, Archibald MacLeish, and Jean Paul Sartre. Under his aegis the association managed more than $1 million in grants for the improvement of foreign language teaching and established the Center for Editions of American Authors. As secretary, Stone was the editor of PMLA, the association's journal, the most widely circulated in the field.

Dean Stone's presidential address at the 1967 MLA convention was a brilliant analysis of the scholar's role. In The legacy of Sisyphus" he likened the task of the humanistic scholar to that of the legendary Corinthian king, compelled forever to roll a huge stone uPhill, only to have it roll back down again. The unceasing obligation of the scholar, Stone reminded his colleagues, is "to roll not one but ten huge stones perpetually up the hill of the age and the place in which he abides." The modern Sisyphus' stones: ignorance and its cure, muddleheadedness and its solution, bigness and administrative devices with which to master it, crassness to be overcome, rapidity of change, salvation of the benefits of permissiveness from a backlash of rigidity, repossession of a broad scholarship, realignment of new knowledge across fields, pursuit of excellence, and assurance of relevance.

Of these, he deems relevance the most important. "The scholar has the opportunity and the obligation to reinterpret the magnificent heritage of the past in ways which make it relevant to the present, and a pad for launching into the future. Or, better, to make his presentation so magnetic that the stu- dent or reader will create for himself immediately a sense of the relevance of the subject to him." Such relevance, he added, is "not to topics of contemporary fashion—budgets, traffic, elections, wars —but to the dilation of the imagination, the freshening of the humanistic point of view, and the steps by which wisdom is gained."

Dean Stone's grants and honors have been as extensive as his contributions to knowledge of 18th century literature and to the world of education in general. An academic alphabet follows his name to signify honorary degrees from Middlebury, Hofstra, and George Washington University, where he taught for 24 years. Recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships, a FullbrightHays Research Fellowship, and one from the Folger Shakespeare Library, he serves as U. S. Vice President of MLA's international counterpart, a director of the American Council of Learned Societies, and consultant to federal educational agencies. He was on the U. S. Committee for UNESCO.

Belying the occasional stereotype of the scholar, this "fierce and unyielding defender of faculty principles and prerogatives," as one honorary degree citation identified him, rode forth from his Ivory Tower in 1954 to fight the dragon of the Internal Revenue Ser- vice—and won. The case established the precedent that research grants are non-taxable gifts rather than remuneration for services—and earned him the lasting gratitude of academia.

Publication of the final three volumes of The London Stage in 1966 marked the completion of 30 years' work by five eminent scholars of English drama. An inestimable amount of painstaking effort had brought programs and playbills, commentaries and cast-lists together for the serious student and recreated the flavor and pace of London theater, progenitor of our own, for the theatrical buff. The work epitomizes, as do other books and articles in the copious Stone bibliography, the kind of assiduous scholarship which preserves or retrieves—"the magnificent heritage of the past."

The continuity of such scholarship is assured, in Stone's estimation. "Scholarship will always operate in three stages: discovery of new and interesting things; editing and/or laying forth the discoveries in such a manner that other scholars can examine them; and critical evaluation. All scholars, especially the young, are anxious to rush into the third—and become instant critics. But the long-time, patient, disciplined, persistent sort of thing ... gives one a familiarity that can be gained in no other way.... A few will still continue in this tradition. But in the past only a few have done this sort of thing."

Dean Stone continues to teach one course a term—"the only oasis in the week." He finds today's graduate students, compared with his generation of doctoral candidates, "probably more highly motivated, more critical, more generally knowledgeable, but less articulate (on paper), less precise than before. . . . The good ones have read widely in associated fields, and bring to English literature fresh points of view from history, philosophy, politics, and psychology little known by their counterparts at Harvard in the '30s. New clusterings and groupings of fields have stimulated their imagination, but have done little for their disciplined attitudes for digging and doing the basics of literary scholarship."

He sees some formalism in the educational process yielding to the independent, informal, tutorial procedures. "If so the knowledgeable tutor will be in demand, for students in the long run will see through the shallowness of perpetually unstructured bull sessions guided by those who just like to talk, rather than by those who know what they're talking about. The preservation, dissemination, and advancement of knowledge are still pretty important, and still require well-educated persons."

And G. Winchester Stone, 20th Century Sisyphus, still zestfully and zealously keeps rolling those stones up the hill.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

December 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

December 1971 -

Feature

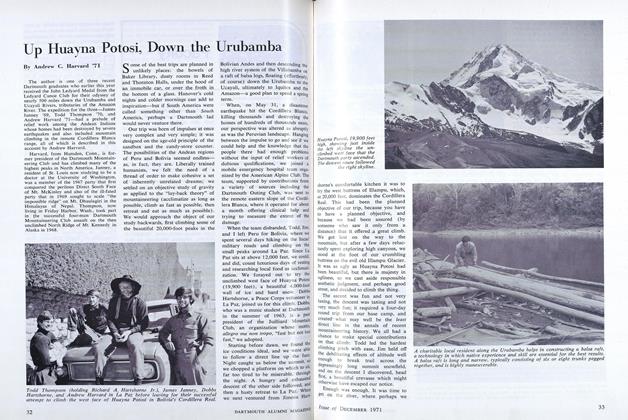

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

December 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees Vote "Yes"

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

December 1971

MARY ROSS

-

Feature

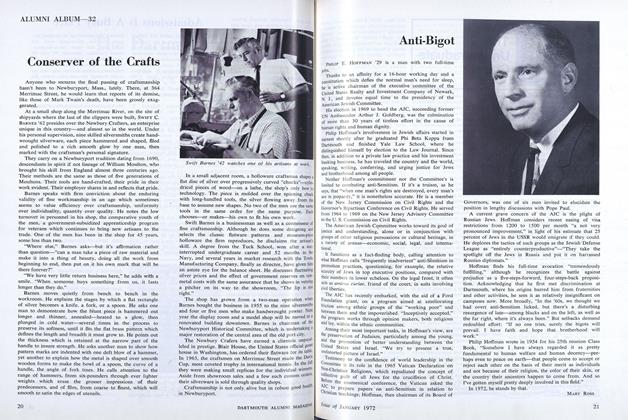

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

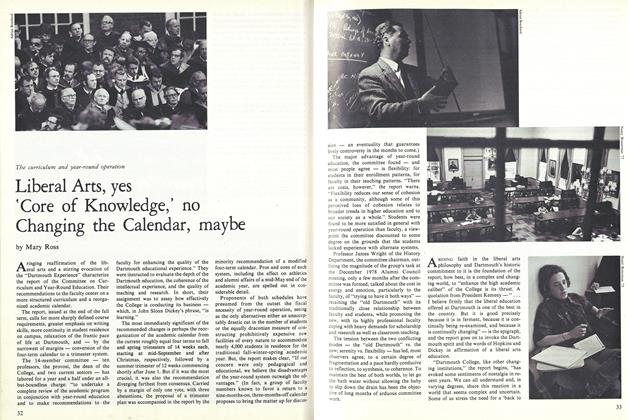

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Article

Article300 Million Years Ago . . .

NOVEMBER 1981 By Mary Ross -

Article

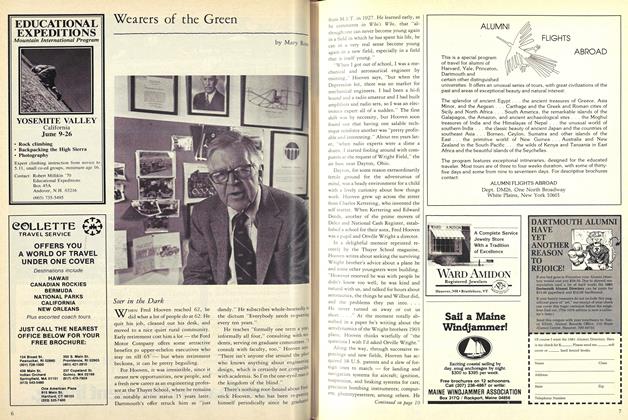

ArticleSeer in the Dark

APRIL 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

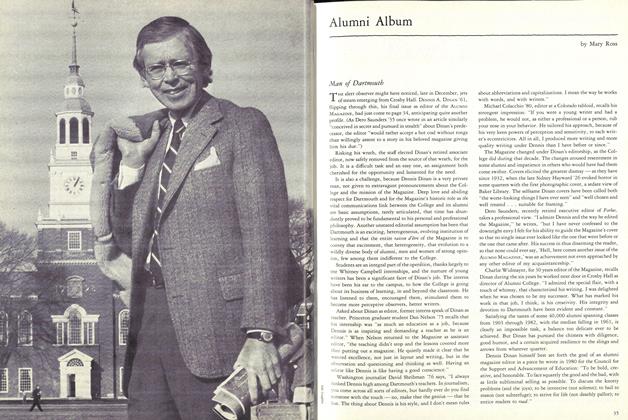

ArticleMan of Dartmouth

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleTha yendanegea Joseph Brant '53: A Reverence for the Past

OCTOBER 1984 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleSEVERAL FRATERNITY HOUSES UNDER CONSTRUCTION

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticlePrize Song Chosen

AUGUST 1930 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Award

JUNE 1972 -

Article

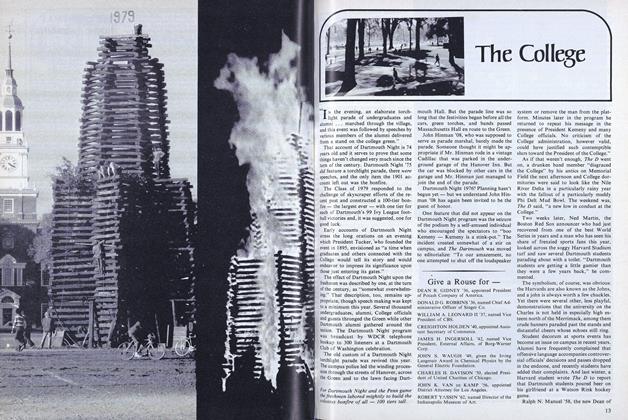

ArticleGive a Rouse for –

November 1975 -

Article

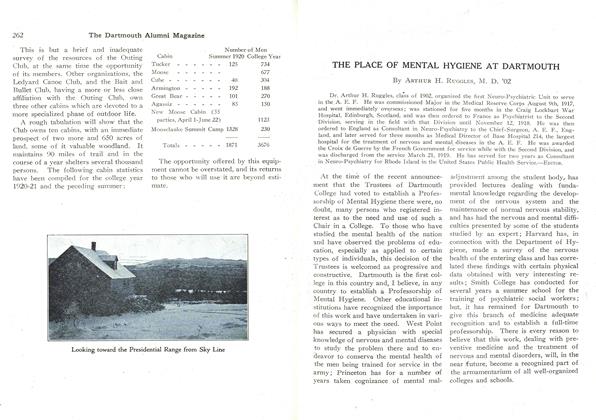

ArticleTHE PLACE OF MENTAL HYGIENE AT DARTMOUTH

February, 1922 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES, M. D. '02 -

Article

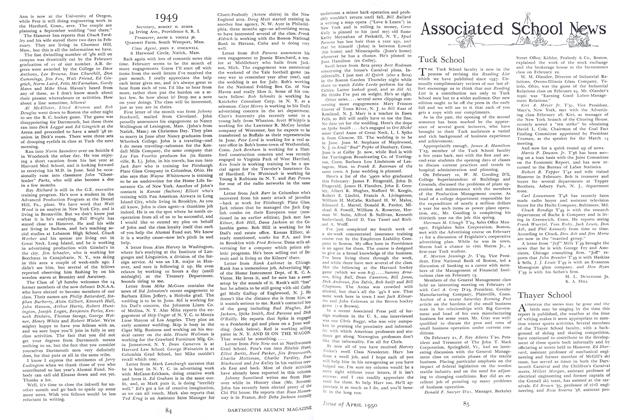

ArticleTuck School

April 1950 By H. L. Duncombe Jr., K. A. Hill