"To take something no one else is interested in and make it beautiful and have it used and appreciated by a lot of people it's the most satisfying, gratifying work I could possibly imagine."

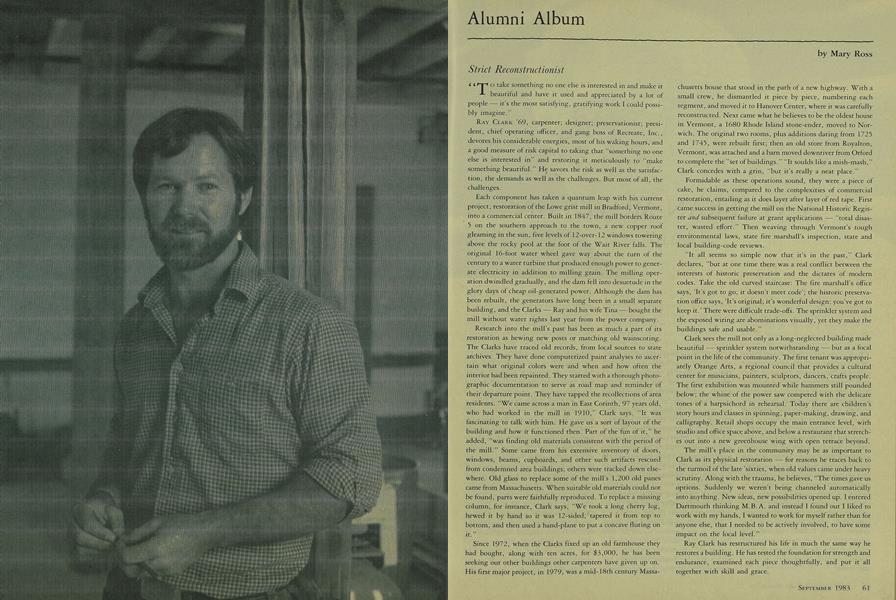

RAY CLARK '69, carpenter; designer; preservationist; president, chief operating officer, and gang boss of Recreate, Inc., devotes his considerable energies, most of his waking hours, and a good measure of risk capital to taking that "something no one else is interested in" and restoring it meticulously to "make something beautiful. " He savors the risk as well as the satisfaction, the demands as well as the challenges. But most of all, the challenges.

Each component has taken a quantum leap with his current project, restoration of the Lowe grist mill in Bradford, Vermont, into a commercial center. Built in 1847, the mill borders Route 5 on the southern approach to the town, a new copper roof gleaming in the sun, five levels of 12-over-12 windows towering above the rocky pool at the foot of the Wait River falls. The original 16-foot water wheel gave way about the turn of the century to a water turbine that produced enough power to generate electricity in addition to milling grain. The milling operation dwindled gradually, and the dam fell into desuetude in the glory days of cheap oil-generated power. Although the dam has been rebuilt, the generators have long been in a small separate building, and the Clarks Ray and his wife Tina bought the mill without water rights last year from the power company.

Research into the mill's past has been as much a part of its restoration as hewing new posts or matching old wainscoting. The Clarks have traced old records, from local sources to state archives. They have done computerized paint analyses to ascer- tain what original colors were and when and how often the interior had been repainted. They started with a thorough photo- graphic documentation to serve as road map and reminder of their departure point. They have tapped the recollections of area residents. "We came across a man in East Corinth, 97 years old, who had worked in the mill in 1910," Clark says. "It was fascinating to talk with him. He gave us a sort of layout of the building and how it functioned then. Part of the fun of it," he added, "was finding old materials consistent with the period of the mill." Some came from his extensive inventory of doors, windows, beams, cupboards, and other such artifacts rescued from condemned area buildings; others were tracked down elsewhere. Old glass to replace some of the mill's 1,200 old panes came from Massachusetts. When suitable old materials could not be found, parts were faithfully reproduced. To replace a missing column, for instance, Clark says, "We took a long cherry log, hewed it by hand so it was 12-sided, tapered it from top to bottom, and then used a hand-plane to put a concave fluting on it."

Since 1972, when the Clarks fixed up an old farmhouse they had bought, along with ten acres, for $3,000, he has been seeking out other buildings other carpenters have given up on. His first major project, in 1979, was a mid-18th century Massachusetts house that stood in the path of a new highway. With a small crew, he dismantled it piece by piece, numbering each segment, and moved it to Hanover Center, where it was carefully reconstructed. Next came what he believes to be the oldest house in Vermont, a 1680 Rhode Island stone-ender, moved to Norwich. The original two rooms, plus additions dating from 1725 and 1745, were rebuilt first; then an old store from Royalton, Vermont, was attached and a barn moved downriver from Orford to complete the "set of buildings." "It soulds like a mish-mash," Clark concedes with a grin, "but it's really a neat place."

Formidable as these operations sound, they were a piece of cake, he claims, compared to the complexities of commercial restoration, entailing as it does layer after layer of red tape. First came success in getting the mill on the National Historic Register and subsequent failure at grant applications "total disaster, wasted effort." Then weaving through Vermont's tough environmental laws, state fire marshall's inspection, state and local building-code reviews.

"It all seems so simple now that it's in the past," Clark declares, "but at one time there was a real conflict between the interests of historic preservation and the dictates of modern codes. Take the old curved staircase: The fire marshall's office says, 'lt's got to go; it doesn't meet code'; the historic preservation office says, 'lt's original; it's wonderful design; you've got to keep it.' There were difficult trade-offs. The sprinkler system and the exposed wiring are abominations visually, yet they make the buildings safe and usable."

Clark sees the mill not only as a long-neglected building made beautiful sprinkler system notwithstanding but as a focal point in the life of the community. The first tenant was appropriately Orange Arts, a regional council that provides a cultural center for musicians, painters, sculptors, dancers, crafts people. The first exhibition was mounted while hammers still pounded below; the whine of the power saw competed with the delicate tones of a harpsichord in rehearsal. Today there are children's story hours and classes in spinning, paper-making, drawing, and calligraphy. Retail shops occupy the main entrance level, with studio and office space above, and below a restaurant that stretches out into a new greenhouse wing with open terrace beyond.

The mill's place in the community may be as important to Clark as its physical restoration - for reasons he traces back to the turmoil of the late 'sixties, when old values came under heavy scrutiny. Along with the trauma, he believes, "The times gave us options. Suddenly we weren't being channeled automatically into anything. New ideas, new possibilities opened up. I entered Dartmouth thinking M.B.A. and instead I found out I liked to work with my hands, I wanted to work for myself rather than for anyone else, that I needed to be actively involved, to have some impact on the local level."

Ray Clark has restructured his life in much the same way he restores a building. He has tested the foundation for strength and endurance, examined each piece thoughtfully, and put it all together with skill and grace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

September 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

September 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

September 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

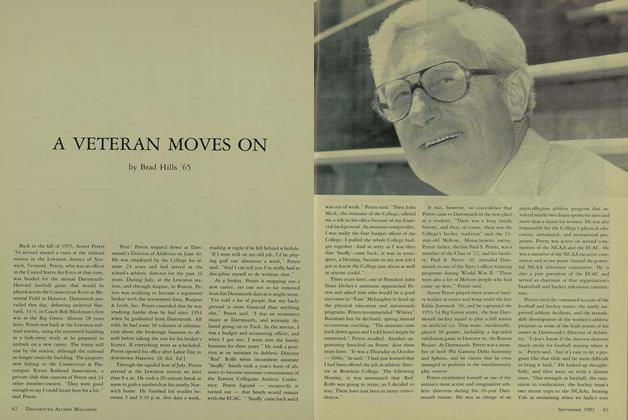

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

September 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

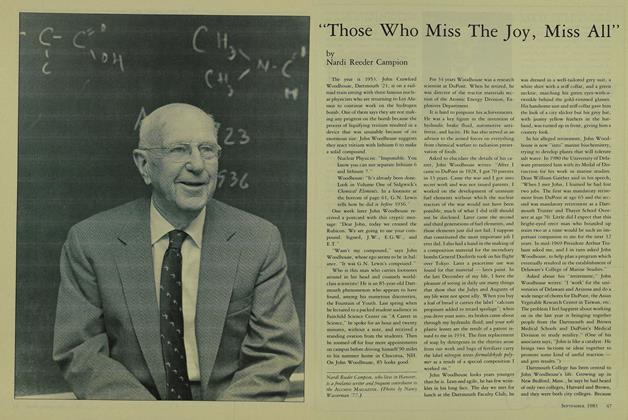

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

September 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

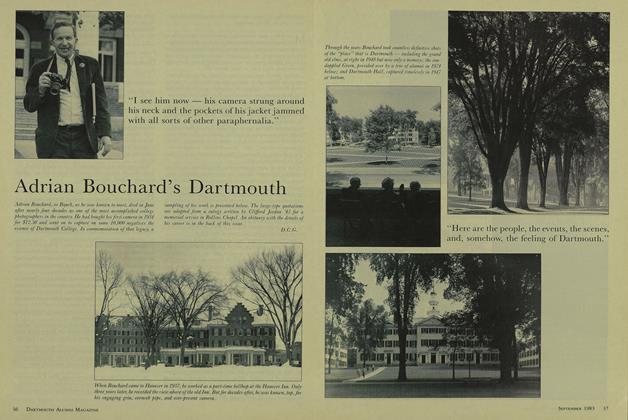

FeatureAdrian Bouchard's Dartmouth

September 1983 By D.C.G.

Mary Ross

-

Feature

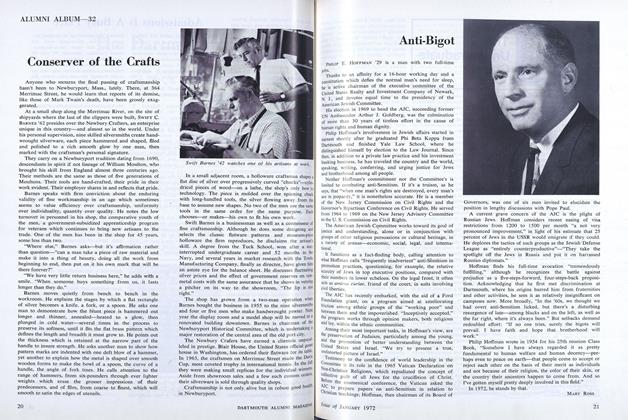

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleTha yendanegea Joseph Brant '53: A Reverence for the Past

OCTOBER 1984 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleHOCKEY SEASON ENDS

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1919 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Leaves

March 1942 -

Article

ArticleHow to Speed Read

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By —Gayne Kalustian ’17 -

Article

ArticleBrave New World

June 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleD.O.C. NEWS

March 1949 By Steven Lazarus '52.