By Prof.Ramon Guthrie (French, Emeritus). NewYork: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1970. 143pp. $7.50.

In 1462, Francois Villon, having lived a lifetime, despite his scant thirty years, looked squarely upon death and felt the power of life. Disgraced, beaten, starved, frozen, imprisoned, he nonetheless felt the exaltation of what it had been to live, to love, to write in Paris. His Paris, a city the more human for being full of contradiction, oppression, absurdity. It was not yet the custom to make art out of everyday life, but that is precisely what Villon set out to do in his Testament, a poetic last will in which the people he knew, the taverns he drank in, the streets he walked and fought in become, in their own guise, symbols for what being human is all about. Villon writes from the edge of the grave, and even (in the Balladof the Hanged Men) from beyond it. He has the wisdom born of innocence, the innocence of those who prize being above having; creating above destroying; giving above taking. Art and experience, past and present, politics and religion, tumble up against one another to form Villon's vision of his world which, 500 years later, we find as intensely human and responsive as Villon intended it.

Five hundred years later, there comes another poet who, like Villon, has lived intensely the great events of his time, or, more importantly, has understood what it was like for others who lived them. Not because he worked the night-shift in a pre-1917 munitions factory, nor because he drove an ambulance at the front, nor because he was a squadron leader in our fledgling air corps, still less because he lived as an expatriate in Paris, nor experienced the frustrations of being an OSS liaison officer with the French Resistance in World War II is Ramon Guthrie able to evoke with such force the paradoxically painful yet exhilarating experience of being human in the twentieth century. Others have done as much or more without being sensitized in this way. No, it has to do, as in Villon's case, with a feeling of the fragility and apparent futility of life. It comes from living on that pain-wracked borderline where slipping into the abyss of death is temptingly easy with its reward of release, of oblivion, as opposed to what ...?

At that extreme fringe of life one is constrained to ask what life has been worth. The attempt to demonstrate the need for that question, and for concrete answers to it in terms of people, places, events, all very much the experience of one gifted observer, is what Maximum Security Ward undertakes. The Maximum Security Ward of the title is at once the intensive care unit of the many hospitals the poet — who casts himself as the archetypal observer-survivor of life's apocalypses: Marsyas, Ishmael, Merlin — has been confined in, and a symbol for life itself. The memories, visions, hallucinations of the bedridden survivor constitute the various sections of this long, intricate poem. Man learns to live, or rather why to live from watching others affirm life when there seems to be no reason for so doing. On the verge of rejecting humanity and slipping over the edge of death, the poet makes one last effort to pin down what it is that has fascinated him about man, even while the world gave cause for disgust.

Ranging back to pre-historic times, but concentrating mainly on the memories of his own life in the United States and Europe, through two wars, Guthrie evolves a category of humanity that has made life something positive. These people, artists, musicians, writers, activists, most of whom he has known, he calls christoi, the chosen ones:

Chosen by whom?

Why, by themselves, I think.

Like Villon, Guthrie exposing hypocrisy, oppression, and pretension opposes these anti-christoid qualities not with slogans but by pointing to the simple but courageous acts of greatness he has seen during his lifetime. Like Villon, too, Guthrie mingling art, literature, and music refuses to distinguish art from life because art is the stuff of life:

Art is life because it reveals to us what it is like to be another, what it means to be a walking carrion at Auschwitz and yet still "want to make a song ... an epic poem. No, a cantata. It has the stuff of a cantata."

The storm speaks.

It sings in me the litany of the christoi, the named and unnamed, the forgotten, though not less close for that, the unknown, the dead who are living their fullest lives now.

A teacher, but never a pedant, Guthrie never tells us anything. His verse is powerful, tightly written, with a love of words and sounds, but the cadenees are not the impenetrable ellipses of a Mallarme. Frequently they are musing, the apologetic murmur of someone thinking out loud. At other times the cadences swell to fill the room with effortless, purposeful sound. Or again, and perhaps most often, the tone is that of easy conversation (it is with a start that one realizes the effort required of the poet to attain that deceptive informality) Like those poets whom he has long admired — Rimbaud, Villon, Browning, Pound — Guthrie knows that a long poem must be varied if it is to be readable. The range and depth of his verse, from intensely personal to irrevocable political commitment (sometimes both at once), make the reading of Maximum Security Ward very much the kind of esthetic experience described in the closing poem of the book:

I have been an instant-lifespan borne, flashflooded, up into an abyss, caught by shrill serene tumult into cyclone depths beyond me, effaced by vision more intense than I could ever know, lulled by a wild accord of warring energies.

As a member of the Dartmouth Collegefaculty, Mr. Nichols wears three hats. He isProfessor of Romance Languages and Literatures, Chairman of Comparative Literature,and Chairman of the Freshman TutorialProgram.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

February 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Blackman Era: Sixteen Special Years

February 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

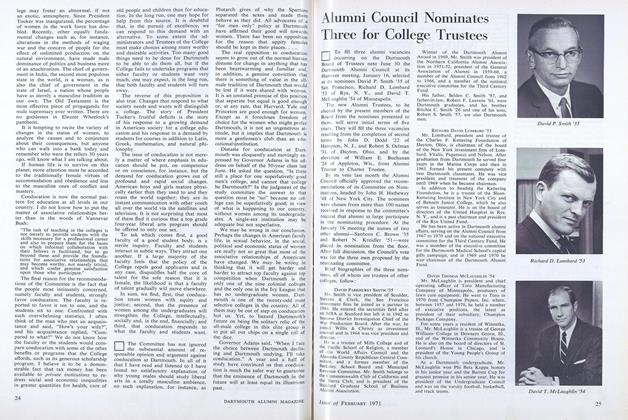

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

February 1971 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

February 1971 -

Article

ArticleA Different View of Vietnam

February 1971 By STEPHEN HART '68 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER

STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE CASE FOR EXPERIENCE RATING IN UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION AND A PROPOSED METHOD

May 1939 -

Books

BooksV AS IN VICTIM

December 1945 By H. M. Dargan. -

Books

BooksTHE OFFENSIVE GOLFER

FEBRUARY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPHILOSOPHICAL PROBLEMS: AN INTRODUCTORY BOOK OF READINGS.

June 1957 By R.C. SLEIGH JR. '54 -

Books

BooksINDEPENDENCE MUST BE WON.

OCTOBER 1964 By R.J.B. -

Books

BooksRENAL FUNCTION: MECHANISMS PRESERVING FLUID AND SOLUTE BALANCE IN HEALTH.

December 1973 By ROY P. FORSTER