Future scholars will find this an interesting campaign

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Although I have an intense personal interest in the 1972 election, I must concede that I had some misgivings when I was asked, as a historian, to write an article about it. Professionally I would feel much more secure writing about the 1872 campaign. The material there seems finite, the issues simple, and of course the results predictable. It would be easy to slip in a few asides about Horace Greeley's fads and eccentricities, to joke about Ulysses Grant's penchant for strong bourbon and black cigars, and to discuss the implications of the election for the reconstruction of the South, the industrialization of the North, and the thrust of American party politics for the remainder of the century.

The current election is a different case. Somehow the Watergate affair, the Eagleton controversy, the shooting of George Wallace, and the debate over the morality of continued American bombing of Vietnam fail to lend themselves to a light approach, perhaps a century hence historians will find a touch of humor in it all. Hopefully not. It is equally difficult to discuss the historical implications of future events. Historians feel more comfortable discussing the campaign and analyzing the results of 1932—or of 1832—than of history-in-the-making. In a year in which Jimmy the Greek was so far in error in predicting the nominee of the Democratic party, the historian will be forgiven if he prefers to predict the results of the election of 1912, and avoids the impulse to prophesy.

There seems to be little doubt at this juncture that future historians will find the 1972 election far more interesting than the voting public currently does. Both major party nominees have described it as a significant test of the sense of the republic and the press has generally defined it in sharp "radical-conservative" terms. The latter are rather elusive and imprecise descriptions. They are alternatively worn proudly and used pejoratively and obviously are the function of both time and space. Somehow social security seems less radical in 1972 than it did in 1935. And a radical as defined by the norms of Dubuque might appear as a conservative in Berkeley. Similarly William Loeb might define both Nixon and McGovern as leftists while Abbie Hoffman finds them boringly conservative.

But while "radical-conservative" are too imprecise to describe this campaign, and while the level of debate has failed to live up to the advance publicity, it would be misleading to dismiss the election as an insignificant contest. It is clear that the 1972 election involves more than Tweedledum and Tweedledee and that it represents the convergence of several powerful historical forces: changes in the nature of our political parties; changes in the constituency of individual parties; a quickened sense of alienation and/or political independence.

The nature of parties: traditionally American political parties have been non-ideological in nature. Presidents have tended to be practical-minded men—obviously with varying degrees of success. The ideologues have largely been in the Congress or the Statehouse where their ideology is more a function of region or constituency than of party. The result has been an ideological melange that often confounds and always amazes the foreign observers. Edward Brooke and Strom Thurmond, Barry Goldwater and Jacob Javits, Ronald Reagan and Nelson Rockefeller can all be good Republicans and unite at Miami Beach. Edward Kennedy and James Eastland, Allard Lowenstein and Henry Jackson, George Wallace and Shirley Chisholm represent bewildering varieties of Democrats.

This certainly is not a recent development. National parties have always been a congeries of state organizations that assembles quadrennially to fight and to compromise. Yet there has always been some touchstone or frame of reference that distilled the practical goal of winning. For most of its history the Republican party—the party of Lincoln—has been the advocate of a strong national government and an activist economic policy. The Democrats—the party of Jackson—have championed state rights and personal liberty (read anti-prohibition).

These roles have largely changed since the 1930's—and clearly not to the mutual satisfaction of all constituents. Republicans have generally opposed federal economic intervention, have been more frightened of strong and militant labor unions, and more concerned with business profits as an essential requirement for a strong and growing economy. Democrats, on the other hand, have campaigned as the champions of the poor and have leaned heavily on the federal government to solve economic and social problems. Both parties have provided homes for strident anti-communists, philosophical internationalists, militant interventionists, and recalcitrant isolationists.

Richard Nixon's announcement that "I am a Keynesian," his wage-price controls, and his continued deficit budgets have thrown much of this into a turmoil. Alienated conservative Republicans have come—grudgingly, in some cases—into line. The McGovern alternative has offered them little choice. They even accepted the President's consensus-building deletion of a right-to-work plank from their platform and have choked down the image of Richard Nixon sipping tea in the Great Hall of the Emperors with Chou En-lai and reciting the poetry of Chairman Mao. The President's flurry of philosophical legerdemain has demoralized the Democrats. Old Democratic truths seem somewhat less compelling when voiced by Richard Nixon. Changes and tensions within the Democratic party in recent years have intensified the problem.

Composition of parties: many historians have noted that the basic historical conflict in our politics has tended to be cultural rather than economic. We have not had a class politics in the European sense. The Democratic party in the period after the Civil War held the allegiance of Southerners, Catholic and German Lutheran Immigrant groups, and some native Protestant farmers whose allegiance could be traced to the Jacksonian elections of 1828 and 1832. Republican supporters (as well as Whig) were the native Protestants (especially the pietistic or evangelical groups, but excepting the southerners) as well as many of the immigrant Protestants. The divisive issues of our politics were not the tariff and monetary policy as much as the control and funding of local schools, Sabbatarian laws, prohibition, and women's suffrage. Natural cleavages among Democrats on these issues—as, for example, between urban Irish Catholics and rural Southern Baptists over prohibition—hindered the development of a truly national party. Republicans have generally enjoyed better intra-party relations because of their relative cultural homogeneity.

The Depression, the New Deal and Franklin Delano Roosevelt deeply affected the party relationships. Pocket-book issues came to dominate and the Democrats were the beneficiaries of a major political realignment. The party increased its support among Southerners and ethnics and added Blacks, Jews, Protestant union members, many farmers, and disaffected intellectuals. This was the coalition that elected Roosevelt four times, Harry Truman once, broke slightly—particularly among farmers, some southerners and Catholics—in the face of Ike's popularity, elected JFK in 1960, and provided the core for Lyndon Johnson's 1964 landslide. It remains the basis for the continued Democratic domination of the Congress.

Yet it is obvious that there are serious tensions and cross pressures among the parts of the Democratic coalition. The political debate of the 1950's and 1960's has dealt increasingly with foreign policy, civil rights, civil liberties, and questions of law and order Benjamin Spock and George Meany may have agreed on Social Security; they do not agree on our Vietnam policy. George Wallace and Ramsay Clark may have agreed on full employment; they do not agree on the rights of demonstrators or the need for gun control. Richard Russell and Adam Clayton Powell may have agreed on the need for the WPA; they did not agree on the integration of schools. Louise Day Hicks and Bella Abzug may have agreed on the minimum wage; they would not agree on abortion. John Connally and George McGovern may have agreed on agricultural price supports; they do not agree on the minimum defense budget- among other things.

It is difficult to generalize from these wide-ranging examples. But surely there are strong indications that culturally-based issues are elbowing aside economic concerns. And culture in the 1970's is a much broader concept than simply older ethnic-community-church orientations. It is a function of complex generational, residential and educational forces. In the primaries many voters perceived George McGovern as the candidate of the counter-culture. He won because of a superior organization, a divided opposition, and a disarming candor that many confused with a new anti-politics. But his victory was against the constituent forces of much of the old Democratic coalition. Therein lay his basic dilemma. McGovern was in the vortex of the fundamental conflicts in our society. He needed Mayor Daley as well as Jesse Jackson, Larry O'Brien as well as Gary Hart. He attempted to include both old Democrats as well as his young supporters and as of October 1 he has failed. The Democratic party lacks both shape and definition. It must be defined before it can be shaped, and to McGovern's dismay this task requires a dialogue rather than a monologue.

Increase in alienation and independence: it was in the midst of the 1888 presidential campaign, a contest not especially noted for sharp debate and basic conflict on the issues, that Senator Daniel Voorhees noted that Indiana was "a blazing torchlight procession from one end to the other." While conceding that hyperbole is not a recent political development, it is nonetheless true that Voorhees was not greatly inaccurate. Without the use of television and radio spots, sophisticated direct-mail campaigns, and computerized scheduling, the pols and candidates in the nineteenth century were able to arouse and sustain tremendous electoral enthusiasm. Political parties were often the only organization, other than a church, that men joined. As such, parties filled a social and cultural as well as a civic need. Perhaps no more than five percent of the voters were "independent." In the same context the political campaign was often the only excitement offered citizens of farm-towns and small cities.

And the people voted. Estimates of presidential voting turnout in the 1870's and 1880's range from 80% to 90% of the eligible voters, with an average drop-off of less, than 10% in non-presidential years. By contrast in recent years presidential turnout has been at roughly 65% and off-year elections barely exceed 50%. 74% and 65% of us watched less than four hours of the 1972 Republican and Democratic conventions, respectively, on television. More than a third claim no party preference.

Politics has become something of a bore and a burden. Most of us in 1972 prefer no greater involvement than a dutiful trip to the polls. And more significantly, our sense of political efficacy has declined considerably and our cynicism has increased correspondingly. Without prejudging any of the incidents, I think it is fair to say that as recently as ten years ago the I.T.T. affair, the Watergate caper, or the alleged tip-off on the wheat deal would have been major campaign issues.

It is this sense of cynicism and alienation that largely explains the unprecedented volatility of the polls and surveys this year. Citizens are concerned about rising taxes, public order, inflation and unemployment, and a widening scope of federal controls. Most importantly, they see little hope of influencing these forces. George Wallace probably tapped into this discontent as effectively as any recent national candidate, although certainly McGovern did in some of the primaries. Many voters viewed these two men as being somehow different from other politicians. The press dubbed the two men the "populist" candidates, and there is indeed some historical basis for such designations. The Populists of the 1890's benefited from the same frustrations and fears that aided McGovern and Wallace. In the late nineteenth century many people shared a perceived loss of control over their own lives, a belief that powerful national and international economic concerns were systematically pillaging their riches and ravishing their pride, and a sense that elites controlled government to the disadvantage of farmers and workers. The cast may have changed but clearly the concerns are relevant to the politics of 1972.

McGovern and Wallace, on the other hand, are products of somewhat different populist traditions. The populism of McGovern's great plains was marked by demands for greater federal intervention in the economy, with a concommitant democratization of processes, in order to protect the small producer. Southern populism was shaped by many of the same forces of discontent but it was characterized by less sectional unanimity, by a greater fear of federal solutions, and by the overriding question of race. While many southern white populists sought black-white political cooperation, they were frustrated by the exploitation of the racial issue by non-populists. Ultimately many of the southern white populists became bitter racists. "Southern way of life" became a codeword for racism. Wallace's populism is the product of these two traditions: the demagogic use of class-oriented economic appeals and the not-too-subtle exploitation of racial fears and fantasies.

To a certain extent, I believe, the resurgence of a populistic politics in the 1960's is symptomatic of the cultural tensions in our society. For most of our history the folk-heroes of our politics have been the farmers and laborers— Bryan's "plain people" and Roosevelt's "forgotten Americans." The issues of public order, civil liberties, civil rights, and foreign policy have cleft us in new ways that leave these groups confused and opposed. As pundits have not wearied of reminding us, most Americans are unpoor, unblack and unyoung. Richard Nixon, particularly through the use of Spiro Agnew, has skillfully made political capital from these new cleavages so that auto worker and G.M. official both support him, although perhaps for different reasons. McGovern's effort to weld together his new constituency with the frustrated old Democratic coalition has not yet succeeded, with post-convention losses from the new perhaps balancing gains from the old. The net effect of a large Nixon majority in November might well be to frighten future politicians from an effort to blend the old, non-racist populism with what we have called the new politics. But here we verge on the prophecy that I promised to avoid. So we will leave these conclusions and judgments to future historians.

THE AUTHOR: Professor Wright teaches courses in United States political history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and also gives a course in the history of the American West, about which he has edited a book, The West of the AmericanPeople. After graduating from Wisconsin State University in 1964, he took M.S. and Ph.D. degrees at the University of Wisconsin, and joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1969. He is chairman of the Democratic Town Committee of Hanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

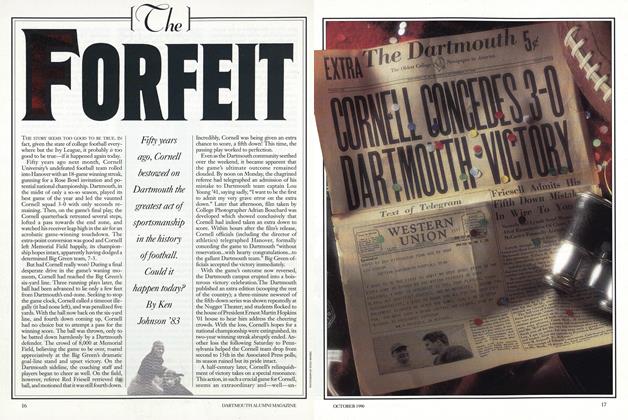

FeatureFour Views of Educational Opportunity at Convocation Opening the 203rd Year

November 1972 -

Feature

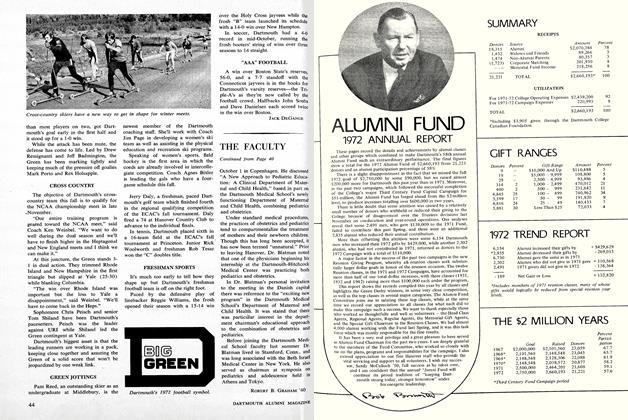

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

November 1972 -

Feature

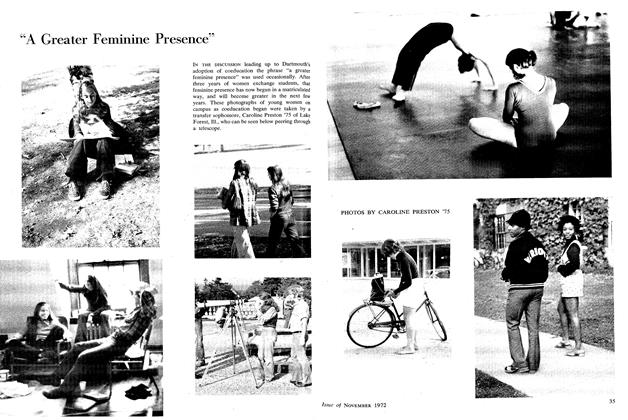

Feature"A Greater Feminine Presence"

November 1972 -

Article

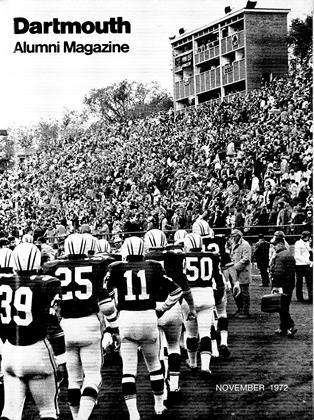

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1972 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1972 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON