IN the extreme northeast corner of New Hampshire, close to both the Canadian and Maine borders, lies a 45-square-miletract of primitive beauty known as the Dartmouth College Grant. It stands as a testimony against time and our mechanized society. It serves as a monument reminding man of his inherent relationship with the land. Its cold streams favored by trout and its animal-inhabited forests form a lasting or perhaps, sadly, the last alternative to contemporary sensibilities.

The region has changed very little since the time John Sloan Dickey formulated the idea of an unspoiled recreational area which every member of the Dartmouth community might enjoy. During his sophomore year at the College, while camping along the banks of the Swift Diamond River, he saw in the sunset of an autumn evening the possibility of man not only coming to terms with nature but coming to a better understanding of himself. Above all else these elements must be seen as contributing to man's involvement with man for the betterment of his world. It is this tradition of genuine concern which marked the administration of President Dickey, and it characterizes the policy of the present Dean of the College, Carroll Brewster. Understanding their love of the College and her relationship with life is paramount in defining their regard for human integrity.

Handling the enormous responsibilities of his office, Dean Brewster always manages to find time to reach out to the students, making himself readily available to their questions and comments. In this spirit Brewster invited six undergraduates to take advantage of the opportunities around them, to share with him their "Dartmouth experience." Specifically this entailed spending . weekend at the College Grant. Easy enough, the six thought. We'll humor the Dean by doing a little hiking, but mainly we'll sit around the plush Management Center and drink beer all weekend. The more we thought about it the better it sounded. Hell, the cabin will be beautiful. The College wouldn't let people such as John Dickey, Dwight Eisenhower, and Brewster stay in the woods without all the modern conveniences, would they? Of course not. And from the window we can look at a tree, maybe see a deer, and commune with nature.

So off we went one Friday, six city slickers and one down-to-earth dean, well stocked with food and amply endowed with yeast and hops blended ever so cleverly by Gussie Busch and Associates. On our northward flight Dean Brewster began to acquaint us with the history of the area. We were surprised to learn that the Grant may be used by any Dartmouth student or alumnus at any time, with a vehicleentry permit, but groups of people who wish to use the cabin facilities should reserve a space beforehand, because of the purposeful limit of such accommodations. Fishing, hunting, recreational and educational possibilities are unlimited. The first two I mention because, yes, Dorothy, there are lions and tigers and bears along with lots of surly trout and various game birds and animals. The area offers year-round recreation, ranging from swimming to snowshoeing and from hiking to photography. The possibilities are numberless and depend only upon one's imagination. Education I include principally upon the advice of Mark Hopkins, who said that he believed the best education came from a teacher on one end of a log and a student on the other. Lord knows at the Grant there are a lot 'of logs upon which you can sit and talk or just sit and think.

Three hours and some minutes after leaving Hanover we stopped our car outside a rustic camp. It wasn't any old wooden camp for this particular one had a sign above the porch which we could all too clearly read—Management Center. Each of us turned to another with a discernible look-Help Well, maybe someone left the thermstat on so it will be warm as toast inside. Not only was there no thermostat but someone forgot to put in an electric toaster; for that matter someone had forgotten to put in the electricity. It as some time after entering the cabin we discovered a new mode of communication. It goes one step beyond audible interpretation, for now we could not only hear each other talk, we could also see each syllable frosted. The great yellow ball of fire had gone down beLow the mountains and the silver liquid in the glass thermometer had waved goodbye to twenty degrees on its descent.

We finally got a fire started in an old wood stove and pulled chairs around the heat. As our bodies warmed our spirits rose, both literally and figuratively Our conversation touched on many areas, one subject seemingly unrelated to the other, but a common bond linked them all. This thread remained aloof, never entering directly but hovering in the back of our consciousness. It prevailed throughout the weeeknd. We began to realize that the woods, the cold, the beer, and the words were as much an integral a part of our liberal education as Baker Library, Memorial Field, or Dartmouth Hall. The experiences offered by the College and the programs available are numerous and flexible. A wide range of activities lies beyond the town limits of Hanover, well beyond myopic outlooks. It's not only sad but very tragic that not enough students actively seek these diverse avenues of opportunity.

We were awakened the next morning in a very sweet and gentle manner. Dean Brewster's dog, Cider, decided she'd like to take a walk. So promptly at 6:00 a.m. in the morning, before the sun was up, she pranced up to each bed and started licking our faces. There are only two other things worse than an unexpected slurp by a dog and they are putting on cold underwear and sitting in an outhouse at 6:15 a.m. Taken separately each possibly may be bearable but, in conjunction, they are death to any but the most strong. But we were fast becoming hearty sons of the wilderness and just managed to survive, I think. Bang the cymbals, beat the drum, watch out nature here we come, off we started through the half light of a misty November morning.

We hiked along the trail which Sam Brungot, long-time custodian of the Grant, had traveled each "firey" morning before his death. He went to look for fires; we went to look for the kindling of understanding. The Grant began to live, fed by the lifeline of two rugged rivers. The rivers still economically support the region. They formed the channel and now the valleys through which trees were transported to the paper and sawmills. We blinked and our imagination took over. Carved in a rock, an inanimate hand with its index finger pointing into the river became a tombstone. We could envision its record. Here lies W. M. Dow killed in a river drive at this spot in 1923. The remnants of a logging camp at once became alive with people. There stood the cook calling the men to breakfast, ladle in one hand and lantern in the other. The men began to stir, each reflecting the hard work of his choosing. Ruddy faces that time had etched with unwavering patience began another day in their struggle for existence. The horses were hitched to a sled which carried the fallen trees. The men turned devotedly toward the river. We blinked again and they were gone, but the river remained as a direct link to this tradition. There is a strange fascination in moving water, a stimulus to thought rivaled only by a roaring fire. It was not lost on us.

Our hike brought us to the edge of many meandering streams, and we stopped often to stare into our depths. Our conversations were interrupted only by the dull concussion of a hunter's rifle echoing over the wooded land. By no means were we so constantly reflective. There were many bears jumping out from behind trees, all resplendent in Levis and Tom's Toggery sweaters. I won't even begin to mention our free association when we came across a beaver dam. Eight hours and fifteen miles later we returned to our cabin for steak and brew. Another night was spent around the fire, split between serious discussions and idiotic antics. But whatever mood we were in, I can't remember a dull moment or a minute that we wanted to be anywhere else.

Whether warmed by the fire, or the beer, or the rising temperature we all slept like logs that night. It was snowing when we got up Sunday morning and our mountain climb seemed in doubt, but never underestimate the sheer bravado of rookie woodsmen. That we were ill outfitted, ill suited, and some just plain ill had no relevance whatever. With a quick rendition of Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" and visions of Everest dancing in our heads we began our ascent. To those who might think this was an impossible task, let me set the record straight. There was a path leading to the top, named Alice and Linda Ledge Trails for the wife and daughter of College Forester Bob Monahan, who no doubt had easily climbed it many times. It wasn't exactly that easy, but even with the slippery snow it took us only 137 very important footsteps and two very near casualties to reach our objective. We sat on a small granite outcropping dangling our feet off the edge trying to kick the tops of the trees 700 feet below us. As we looked out upon the Grant, it had taken on a new perspective. The snow had shrouded the valley in silence. The hard and softwood trees caught the snow in different ways so the land looked like an intricate lace shawl. The two rivers bisected the region, meeting at a juncture one mile below and to our right.

Suddenly someone said it was a beautiful day for a swim and our hearts soared like hawks. Insanity? In less time than it takes to say we slid down the mountain, had a snowball fight in front of the cabin (in which Dean Brewster was annihilated), got our towels, and drove to the river. There we were upon a rock, standing in two inches of new snow, looking down on an ice-covered river. Well, sports fans, there comes a time in everyone's life when, faced with temptation and buffeted by fortune, he must reach down to grasp at that last trace of courage and pull himself out of the straits of despair. Well, unfortunately this was not one of those times. So there we stood, six undergraduates, stark naked, outlined against the falling snow. Rational thinking had long since been abandoned. So with one hop, two skips, and six bloodcurdling screams we jumped into the river. To say it was cold, ice cold,, or freezing cold would be the ultimate understatement. Somehow, despite contracted muscles, quick breathing, and a shortened life span, we made it back to the cabin.

We had changed over the weekend. The difference was probably not noticeable. No great truths were discovered. No valuable insights were attained. Our conversations hardly achieved deep philosophic or intellectual proportions. Yet it was important that we had experienced the Grant. Perhaps our eyes were opened just a little more to the world outside us and the world inside us.

Our last impression of the Grant pretty well reflected our weekend. In the waning light of a snowy evening we stood fifty feet above the river. We watched silently as the river wound and forced its way through an opening too narrow for the volume of water carried by its current. Directly across from us the tree line began and continued up until we couldn't bend our necks back any farther. The spruce and fir trees were dusted delicately with the white, wet snow. Though it was impossible to reach over the chasm to the trees, we tried. We wanted to brush away the snow and leave our initials upon the land, as if they would stay there forever.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep But I have miles to go before I sleep, and miles to go before I sleep.

THE EDUCATIONAL ADVANTAGES of the Dartmouth Grant are a special interest of Tony Owens '71 and Don Nichol '72 who are conducting seminars there and may compile a field guide to the area With Mellon Foundation funding, they are researching the effects of snowmobiling on the environment of the Grant, and also are making a census of the kinds and numbers of animals living there.

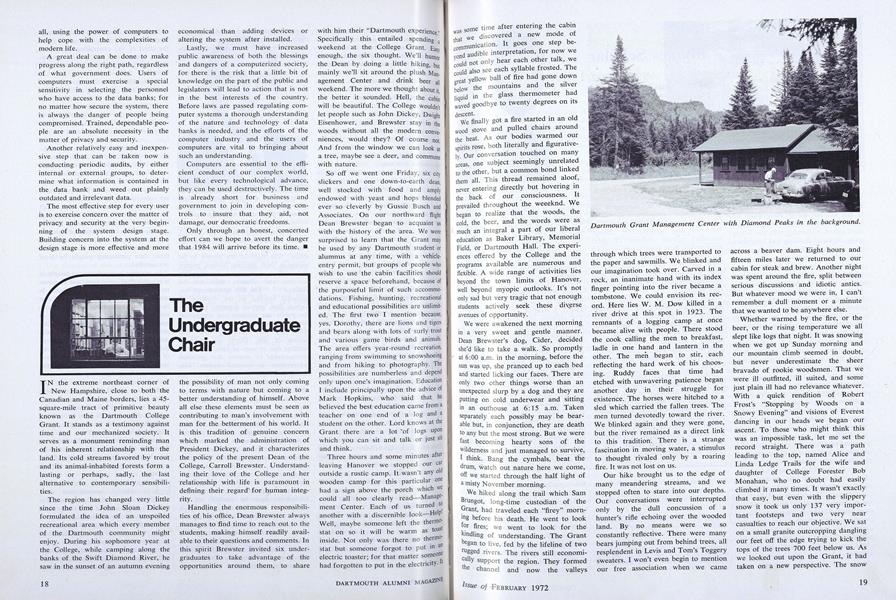

Dartmouth Grant Management Center with Diamond Peaks in the background.

Mark Heller, who resides in Manchester,Conn., completed the final term of hisundergraduate course in December. Hisarticle about the trip to the Dartmouth.Grant was written while he was still anundergraduate and was one of his lastextracurricular efforts before earning hisdegree and taking off for Europe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972