When the pick of the world's amateur winter sportsmen assemble for the 1976 Winter Olympics in Colorado, they will compete on slopes and trails whose contours are as familiar to JAMES R. BRANCH '52 and Joseph Cushing Jr., his Dartmouth roommate and classmate, as their own palm prints.

Branch is president of Sno-engineering, a N. H., ski-resort consulting firm commissioned by Denver to evaluate potential sites for the '76 Games. Cashing is vice president in charge of mountain design. president in charge of mountain design.

A young company which has soared to international prominence with the ski boom, Sno-engineering offers services unique in the trade. Many firms are consultants; Snoengineering is prepared to undertake complete master planning. They will supervise construction, hire and tram personnel, even follow up to insure that parking patterns and cafeteria lines run smoothly.

Their list of more than 300 clients in the U. Canada, and Mexico reads like a blue-ribbon directory of North American resorts. Their 17 current projects range in scope from a 250,000-acre tract in Ontario to a strategic 25-acre piece, key to a large undeveloped area beyond.

The complexity and enormous costs of present-day ski resorts—a far cry from an era when intrepid enthusiasts sought a good hill and, maybe, a rope tow demand the combination of sports know-how and business acumen that Branch, a Dartmouth ski team member and '53 Tuck graduate, and his associates represent.

Branch joined Sno-engineering in 1967 after seven years in Alaska, where he developed a large resort near Anchorage. Sel Hannah '35, Dartmouth skiing great, was president then, and Cushing, whom Branch calls the best in the country, perhaps .in the world," in mountain design, was working with him on terrain.

"It was a matter of where we wanted to live," Branch says, explaining how they came to Franconia. He and his wife had decided that Alaska, exciting as it was, was less than ideal for raising their three boys. Mountains were a sinequa non, and he toured the west, weighing opportunities, before a trip to New England. A chance meeting with Cushing, an introduction to Sno-engineering, and he called his wife in Alaska, "We're moving to New Hampshire.

The environment in Franconia is conducive to efficient work as well as good living, Branch finds. The staff is small and congenial—five men there and three in Colorado. We should all be vice presidents," he says, but corporate structure requires a president, "and I drew the short straw."

Sno-engineering has resisted the Great American Dream of bigness, preferring to remain what its president calls lean and mean." Low overhead permits painless candor in accepting or rejecting commissions. Instead of a large staff, the firm has available a gamut of specialists architects, mountain ecologists, geologists, engineers—they call on as the specific job demands.

Of the permanent staff, Branch says "everyone is capable of doing the other man's job," though each is a specialist too. "My bag is project coordination and highly detailed economic analysis, but I can do preliminary map study and trail design.... We can't get stale; there are too many facets to the work. If a guy gets tired of the map room, we send him out to Colorado to supervise construction.

Computers play an important part in this sophisticated business. After physical evaluation for quantity and quality—how will the terrain work for what kinds of runs? how many will they accommodate? how much fun will they be for skiers of varying skills?—the site is weighed in economic terms: will it pay? "The site can be the greatest in the world, but if it won't produce a reasonable return on the investment, it can't be developed." Information from preliminary studies is fed into a computer and measured against Sno-engineering's "econometric model," a compilation of the best features of all known ski resorts. The computer indicates precisely how, where, and to what degree preliminary projections vary from ideal requirements, down to anticipated fuel use and the cost of hamburgers. "Properly planned, ski areas can make money; they don't have to be 'loss leaders' for real estate developments," Branch says.

Although he sees some leveling off in the growth rate of the ski industry, "the numbers of people involved will be astronomical" at the 12 percent annual increase Branch predicts for the next few years. He points to largely untapped potential in the South, where technological improvements in snow-making equipment have made development feasible.

The Olympic job is a feather in the firm's cap, but it has made for some headaches under that cap. We re very pleased to be doing it," Branch says, but he concedes that it is a complex, time-consuming, sometimes delicate job involving an international mix of land planners, politicians, and committees. "It's given us a very high profile"—a posture hardly to be avoided by men who redesign mountains.

James Branch '52 (right) with Joseph Gushing '52

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1972 By MARK HELLER '70

Features

-

Feature

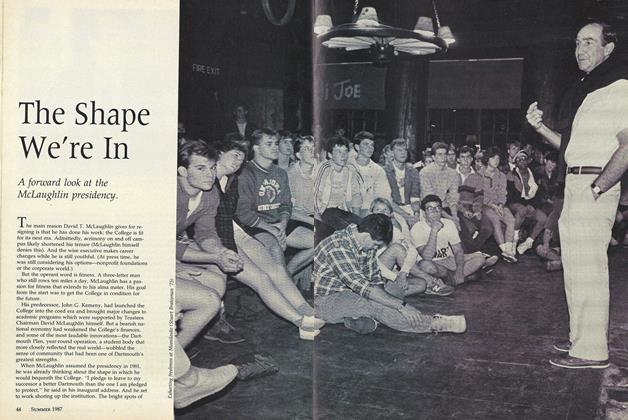

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

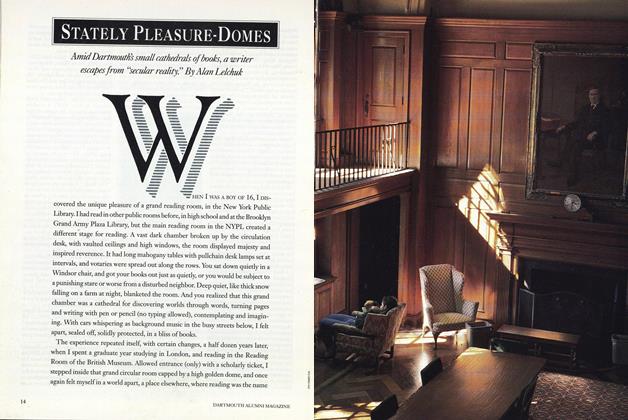

FeatureStately Pleasure-Domes

MAY 1990 -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Feature

FeatureNew York Art Show Planned

JANUARY 1970 By H. ALLAN DINGWALL '42 -

Feature

FeatureA Rare Kind of Movie Star

October 1960 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

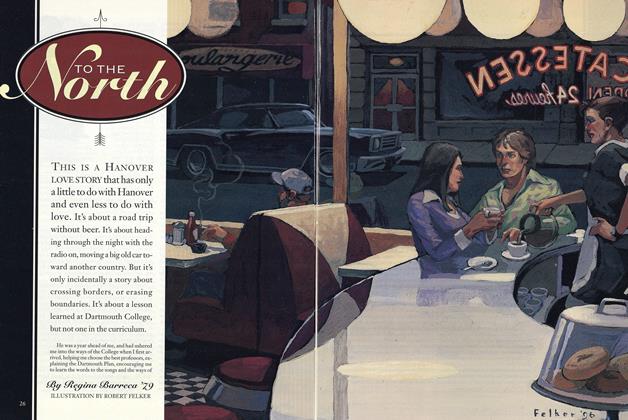

FeatureTo the North

JANUARY 1997 By Regina Barreca ’79