Avalon Professorin the Humanities

Perhaps it's his boyhood spent on a farm in the Appalachian mountains of Virginia.

Perhaps it's the soft twang in his speech that seems to have as much of Texas as Virginia in it and that persists despite a solid Midwest education and nearly 15 years in New England as a member of the English faculty at Dartmouth.

Perhaps it's his total immersion in American literature - from the frontier mythology of James Fenimore Cooper to the "coming of age" of J. D. Salinger - that enables him to range easily in conversation from coast to coast and through two centuries of evolution in American thought.

There's an element in it of sheer intellectual energy that makes listening to one of his lectures as exhilarating as fireworks on the Fourth of July.

Other ingredients might be his openness, his dogged honesty in the search for substance, and his impatience with pretensions - traits Americans like to think of as particularly American.

Or perhaps, as his features alternately flash enthusiasm and furrow in weariness, the once-square contours of his face lined and leaned by the years, there is a suggestion of that American prototype, Spencer Tracy.

Whatever the mix, there's something that lends a special aura to James M. Cox, who to this observer of the Dartmouth scene personifies to a rare degree the American heartland.

Like Dartmouth, Cox is a product of place and time. He was born in Independence, Va., in Blue Ridge country not too far from where the historic Wilderness Road turns west toward the Cumberland Gap. There, Daniel Boone once guided pioneers beyond the borders of the original colonies in one of the first n'g initiatives in America's westward migration.

ox was brought up on a 365-acre cattle farm which only got electricity in 1937, when he was 13 years old. He learned to hay and do other farm chores with horses, not tractors, and the family ground its own our in its own mill. This boyhood - full of hard work on the farm - provided him with Personal links and insights into 19th century pastoral America that most urban and suburban Americans today can only dimly imagine.

Yet because his father was also superintendent of schools in Grayson County, he left the farm following graduation from high school in 1942 and entered the University of Michigan intending then to study journalism. After one year, World War II submarine service in the Pacific intervened, and when he returned to Ann Arbor in 1945 he found journalism courses "a bore."

"I felt I could learn better and faster to be a newspaperman on the job," Cox recalls, so he shifted to an English major with a vague sense that perhaps he would follow his father's example and teach high school English. "Like so many students today, I really didn't know what I wanted to do then, and my memory of that time makes me sympathetic with our students wrestling with that same problem now."

Ironically, the man who was destined two decades later to receive the Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching was almost lost to teaching following his graduation from Michigan. The reason: as an honors major, Cox was immediately hired by the university to teach freshman composition. "It was not a good experience," he remembers. "I was too young and inexperienced and was literally swamped with papers to read and correct." That was not teaching but "academic clerking," so he quit and went back to school, earning an M.A. for his work on Keats and the English Romantic poets.

Thinking he was by then ready to teach, he applied to 15 colleges in the south for a position and got two job offers along with acceptance to a summer session of the highly-regarded School of English at Kenyon College in Ohio. "I'll never forget what one of my teachers, Austin Warren, then advised me," Cox says. "He urged me to take the summer course for reasons that kept things in perspective. He told me that if the school offering me a teaching job was a good school, it would be glad to wait a couple of months and get a better trained teacher. He added that if the school were unwilling to wait, I didn't want to go there anyway."

It proved crucial advice, for during that summer, under the tutelage .and encouragement of such teachers as Kenneth Burke, to whom Dartmouth later gave an honorary degree. Cox turned a corner in the development of the self-confidence essential to creative thinking and good teaching. That fall, in 1950, he picked up the position that had indeed been held for him at Emory and Henry College in Virginia, and he blossomed there. He was paid $2,500 as an assistant professor teaching five courses a semester and serving as supervisor of the college paper, but it. was "a good experience." "The school was small and certainly not rich," he recalls, "but the students were good, and I learned one important thing. I learned I really liked teaching."

But by 1952, Cox realized that if he were going to make teaching his career, he needed the further scholarship required for a doctorate. He left Emory and Henry and went north again to Indiana University's School of Letters.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, he did his dissertation on Mark Twain, whose vernacular humor caught the spirit of an earlier America. But symptomatic of the critical honesty he applies to everyone, including himself, he no sooner earned his doctorate in 1955 than he decided he had approached his subject all wrong. "Like so many others," Cox says, "I virtually ignored Clemens' humor in my dissertation and tried to be profound about everything else - his philosophy, his morality, his theology and view of man."

After chewing on this for five years, he took a leave of absence and totally recast his work to treat Mark Twain as a humorist. The result, Mark Twain: theFate of Humor, was published in 1966 by the Princeton University Press as a definitive study of Mark Twain's penetrating use of humor and of the place of humor on the American scene.

"The American people are a humorous people," Cox notes, "but our humor is really a defense mechanism. We really don't have a native language; it was imported from England. And as long as Americans feel English represents a higher culture, we'll continue to have a strong tradition of humor in our literature. It's our defense."

Yet Cox, who seems to have an antennalike sensitivity to language, feels this nation is making good use of its adopted tongue. "Recognition of American literature really only came of age during the Depression," he says. "Much had been written before, of course, but somehow that trauma caused us to look in on ourselves, and on American campuses English departments began to acknowledge that the study of Hawthorne and Melville could and should compete with the study of Milton. It was only then that the study of American literature, once as suspect as black literature was until recently, became recognized as a respectable body of scholarship."

In characteristic fashion, with scarcely a pause, as his ideas seem to race each other for expression, he adds, "But in America's literature, one can see great power. As we broke with the genteel traditions of England, represented in this country by Longfellow, Whittier, Holmes and others, our writers put great pressure on the language to make it yield to speak to our times. In that sense, we're blessed by the fact that our language is foreign, is not deeply ingrained in tradition that would box us in."

Yet, if this freedom has given American English the vitality to give unique expression to the forces of the modern age of technology and mass culture, it also has placed great burdens on the creative writer. Cox has currently in the works books on Hawthorne and American autobiography, yet he acknowledges that at the moment he's stalled. "I don't want to write just another book," he insists. In the way of a farmer planning ahead, he is taking time to walk mentally around his subjects to find the distinctive topography he needs for guidance. And with the candor which continually surfaces through his conversations, Cox says, "You know, it's hard to write about something important. I thought once it might ease up as I became skilled in craft. But it's as hard as ever."

Cox joined the Dartmouth faculty as an instructor in 1955 after Arthur Jensen, then Professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, talked to him during a tour of Midwestern universities looking for new Ph.D.'s from outside the East to bring "new blood" to Dartmouth. Cox returned later to the University of Indiana for a few years, but rejoined the Dartmouth faculty in 1963, as an associate professor. He became a professor in 1965 and was named in 1970 to the Avalon Professorship created by the Avalon Foundation, renamed the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

In addition to the Harbison Award and a fellowship of the American Council of Learned Societies, Cox has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Dartmouth Faculty Fellowhip. He has also edited a book of essays on Robert Frost.

But those were the products of yesterday. Now, between the demands of teaching and the diversions of his son, five daughters, and wife in their hillside home in Vermont, he intends to return to the study of Hawthorne and to try once more to glean from the 19th century writer new insights for contemporary man.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

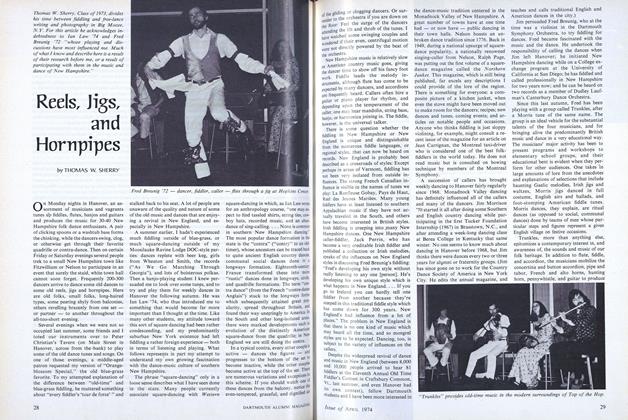

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

FEBRUARY 1973 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJOHN W. FINCH

APRIL 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleROBERT E.GOSSELIN

November 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleERNST SNAPPER

January 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleS. MARSH TENNEY

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

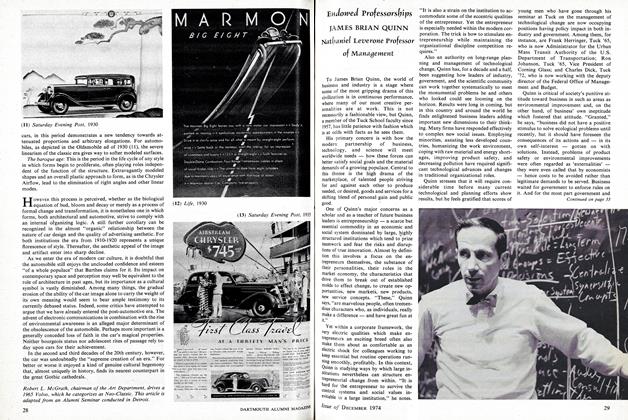

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN PALESTINE RED CROSS EXPEDITION

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

JUNE 1930 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Plaque

April 1942 -

Article

ArticleWaiting List for Alumni College.

JUNE 1966 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

July/Aug 2013 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Intellectual Life

DECEMBER 1929 By Instructor Chauncey N. Allen