By Sidney B.Cardozo '38. New York: Japan Society,Inc., 1972. 100 pp. With 154 illustrations,eight in color, and seven photographs ofRosanjin.

Delighted with the ceramics of Rosanjin, Mr. Cardozo, a resident of Tokyo, tracked him down, received a cold-shoulder rebuff, but eventually fashioned a friendship lasting until the master potter's death at the age of 76 in 1959. Now an authority with a world-famous collection, Mr. Cardozo writes about the artist's productivity and genius, his generosity and his truculence, his frugality and his profligacy.

Rosanjin is unique in his mastery of techniques: Blue and White, Oribe, Shino, Bizen, Iga, Shigaraki, and Ki-Seto. His omnipresent originality in shapes, decorations, and surfaces is shown by the illustrations of vases, lamps, bowls, plates, sake bottles, chopstick rests, spoons, pitchers, platters, jars, braziers, lid rests for tea ceremonies, tea pots, and food containers.

Mr. Cardozo's profile is interspersed with seven photographs of the potter at leisure and at work. Born Kitaoji Fusajiro, he adopted the motto Doppo (Lone Wolf) because, seeking to become the pupil of two calligraphers, he was rejected, and so he resolved to work independently and fiercely. Rosanjin is the amalgamation of Japanese words meaning Mountain and Person, which, placed together, suggests a poetic suffix: Man of the Mountains. The image is that of a sage in isolated contemplation, a figure often tucked away in. a corner of a Japanese landscape painting. The prefix Ro means foolish, adopted because the potter brooded over a wonderful world peopled by fools, himself among them.

In 1925, Rosanjin, a gourmet, became adviser for the Hoshigaoka Saryo (Star Hill Tea Place), Tokyo's finest restaurant. To guarantee it proper dishes, he founded the Hoshigaoka kilns. When American bombers forced him to close down, he concentrated on lacquer. In later life he took delight in shocking foreign guests with bizarre foods: entrails of sea slugs, rice-paddy snails boiled in soy sauce and ginger to kill the paddy stench, and green olives "tasting like a woman." His perpetual concern, however, was individualized dishes for serving his unsurpassed Japanese cuisine. His often quoted remark has become a cliche : "Dishes are the kimonos of good food." Beautiful as objects of art, in actual use his ceramics and lacquer achieve even greater felicity.

In 1954 Rosanjin at his own expense made his only excursion into the Western world with 500 pieces for exhibitions in San Francisco, New York, London, Paris, and Rome. Stories are firming into legends about his truculence. He personally presented Picasso with a choice pot contained in the usual signed paulownia wood box. Paying no attention to what was inside, Picasso rhapsodized over the box. Rosanjin exploded: "You are a simple child, content with simple presents, and you know nothing of ceramic arts."

Rosanjin's colossal output has enriched the finest Japanese restaurants and inns. His reputation keeps on increasing in France, Holland, Scandinavia, and the United States. Mr. Cardozo has particular skill in showing why the Japanese attach such importance to pottery and lacquer as objects of culture and taste playing a major role in daily life. And he is at this best in sketching the portrait of an eccentric genius and gourmet, humble and arrogant, at odds with his fellow men and at one with nature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Future of Liberal Arts Education at Dartmouth

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

June 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Feature

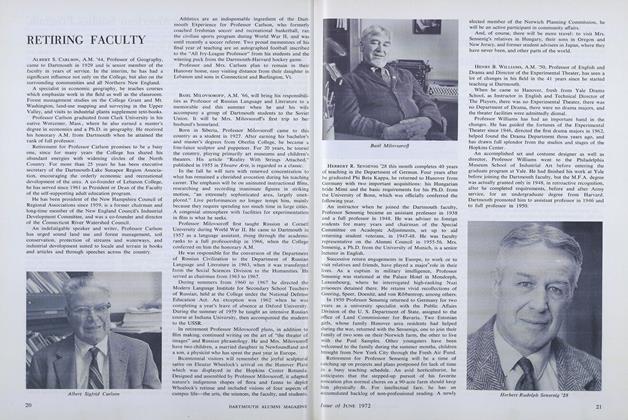

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

June 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Myth of the Munich Analogy

June 1972 By STEPHEN C. THEOHARIS '71

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleMEN VS. MICROSCOPES

December 1947 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleEnglish Climbing Boys

November 1949 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE'S EPISTLES TO SEVERAL PERSONS (MORAL ESSAYS).

MAY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

Article1972 Course Guide

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFLAUBERT IN EGYPT: A SENSIBILITY ON TOUR. A NARRATIVE DRAWN FROM GUSTAVE FLAUBERT'S TRAVEL NOTES & LETTERS

December 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksVERMONT ALBUM: A COLLECTION OF EARLY VERMONT PHOTOGRAPHS

December 1974 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksTHIDWICK THE BIG HEARTED MOOSE,

November 1948 -

Books

BooksAn Authoritative Obituary for "Well-Roundedness"

June 1962 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksIDEOLOGIES AND UTOPIAS: THE IMPACT OF THE NEW DEAL ON AMERICAN THOUGHT.

JANUARY 1972 By ELMER E. Smead -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN CAMPAIGNS OF ROCHAMBEAU'S ARMY 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783. Vol. 1. THE JOURNALS OF CLERMONT-CREVECOEUR, VERGER, AND BERTHIER. Vol. 2. ITINERARIES AND MAPS AND VIEWS.

MARCH 1973 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksGUIDE TO PEDAGUESE.

APRIL 1965 By RICHARD G. JAEGER '59 -

Books

BooksTHE QUARRY.

JUNE 1964 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56