Once we might have watched the peregrine falcon in New Hampshire. But in the last twenty years the species has disappeared from most of North America and Europe, so quickly that scientists fear it may vanish entirely. Once even entering cities to nest, today in North America it is restricted as a nesting species primarily to the Arctic.

Peregrine study has a long tradition at Dartmouth. Students under the late Professor Charles A. Proctor '00 watched New England peregrines in the 1930s and '40s. Dr. William G. Mattox '52, leader for our Greenland research, deepened his interest in falcons when as an undergraduate he worked with Professor Proctor and former College Naturalist Douglas E. Wade. Mattox particularly wished to include Dartmouth students in his study of the little known Greenland peregrines. Peregrine research has an urgent purpose. We must understand the details of the species' behavior and disappearance now if scientists are to learn it can be saved and the public made to care that the last peregrines survive.

We flew to Greenland on Air Force cargo planes. Dave and I set up a camp near one of the peregrine nest cliffs where the falcons have returned year after year to raise their young on inaccessible ledges. Our cliff" was 700 feet high. The adults were such aggressive defenders of their young that we had to watch them through a telescope from the cliff" base 100 yards west of the eyrie. When we came closer than our look-out station, both parents constantly screamed, circled, and dived over our heads.

During early summer, the female sat upon the scrape, a hollow in the dirt that serves as nest for the peregrines. The male, or tiercel, often would perch on the cliff and survey the valley and hills south; at intervals he softly called kaaa kaaa kaaa. Or else he might soar before the cliff on his long pointed wings, gliding and circling in the wind until he rose higher than the mountain ridge, suddenly rushing over the top on the start of his hunt over the tundra. The peregrines catch birds as prey, pursuing them at speeds reaching 180 miles per hour as they dive for the kill. In one violent strike there is an explosion of feathers and the neck of the ptarmigan, a northern grouse and favorite prey of the falcon, is broken.

Our tiercel caught most of the food for his mate and the young, patrolling several square miles of tundra. When he flew in from the wide tundra he called shrilly to announce his return. The female would leave the scrape, fly out to meet him, both falcons screaming, both so filled with life, and she would beat up under his spirals to snatch the prey from his talons with hers, and then drop on motionless wings to the cliff".

Dave and I sat day after day on the look-out watching the peregrines. The tiercel would leave for an hour or more on his hunts. Grasses hid the scrape, and we could see the brooding female only when she stood to shift her position. Mosquitoes in swarms joined us and many times we wished them destroyed. But it is man's effort to control these and other insects that threatens the peregrine (and many other species). Certain of the pesticides - hydrocarbons such as DDT and dieldrin - remain for long periods as poisons in the environment. They collect in the fat tissues of animals, and in high doses kill not only insects but much larger animals. The peregrines eat many birds contaminated with the chemicals and eventually become unable to reproduce because the chemicals interfere with calcium deposition in the eggshells. This results in thinner eggshells which are prone to premature breakage in the nest. When the old birds die no young peregrines are available to replace them at the nest cliffs.

We avoided approaching the eyrie during the first half of the summer, for with the female off the scrape and flying, the eggs or the young would soon chill and die. But in mid-July, when the young (or eyasses) were old enough to control their body temperatures, we erected a blind on the nest ledge itself. Dave fixed a 200-foot rope up from the cliff base so we could climb to the ledge. When Dave or I had hidden in the blind, the peregrines would no longer see any danger and would continue their normal activities. We took shifts watching the four eyasses. They were covered with white down, and clumsily flopped their stubby wings and stumbled over their early developed feet to produce a bustling motion that never moved them far.

When the female brought them food, they all sat up and peeped. She held the prey with her talons and, bending over it, tore off" small bits of flesh. She touched the tidbits to an eyass's beak, and it would snatch the morsel. The four would line up before the female, and if one in the back row received little at one feeding, at the next it would alertly bustle to the front row. As they grew older, and dark feathers showed in their wings and tail, the eyasses would try to take their own bites. At first the female would pull the food away, but soon she simply would drop the prey on the ledge, and one eyass would grab it and eat.

The peregrines collect pesticides through their diet. We noted what bird species they took as prey, but we do not know what dosage the peregrines receive in the Arctic to compound their exposure to the hydrocarbons on their long winter migrations into South America.

In addition to observing at an eyrie, Dave and I helped Dr. Mattox and the other group members hike throughout 1000 square miles of tundra during the two summers. We located all nesting peregrines in the area in the hopes of discovering whether the Greenland peregrines are still reproducing normally. By rappelling down ropes to the nest ledges we counted and banded the young at each eyrie.

In both years we found a healthy rate of reproduction, with an average of between two and three eyasses at each eyrie. The Greenland falcons have not begun the decline that now is spreading into other parts of the Arctic. Yet their eggshells are dangerously thinner than formerly, one sign of pesticide contamination. Unless measures are taken to protect these northern falcons from the hydrocarbons, they, too, may be exterminated, thus destroying another link in the fragile ecosystem. And the experience of watching peregrines will then not be available; not in New Hampshire, not in Greenland, perhaps not anywhere.

Opposite, a female peregrine scans the tundra - and the photographer - whilefeeding on a ptarmigan. The bandedyoungster above is about four weeks old.

These photographs, taken in a time sequence of one minute, show the femaleperegrine returning to the nest with freshlycaught prey in her talons, shredding it, andthen feeding a piece to one of her young.

These photographs, taken in a time sequence of one minute, show the femaleperegrine returning to the nest with freshlycaught prey in her talons, shredding it, andthen feeding a piece to one of her young.

These photographs, taken in a time sequence of one minute, show the femaleperegrine returning to the nest with freshlycaught prey in her talons, shredding it, andthen feeding a piece to one of her young.

In the summer of 1972 and again in 1973,Jim Harris and Dave Clement formed partof a five-man team that travelled toGreenland to study the peregrine falcon.Their research was supported by a specialfund created at Dartmouth in 1970 by a$100,000 grant from the Richard KingMellon Foundation of Pittsburgh. TheMellon Fund has assisted over forty undergraduates in practical work related toenvironmental problems. Other projectshave ranged from development of the environmental studies library at Dartmouthto the location of heavy metals in a mountain ecosystem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCITIZEN SOLDIERS

October 1973 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

FeaturePort Professional

October 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1973

October 1973 By STEPHEN H. QUIGLEY, JAMES T. BROWN

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWhite House Fellow

MARCH 1968 -

Feature

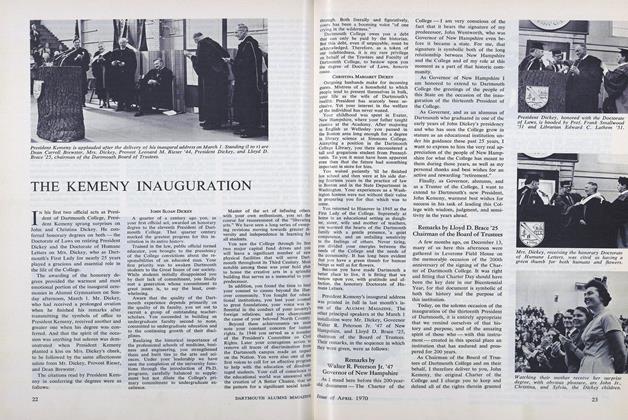

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

APRIL 1970 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

OCTOBER 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

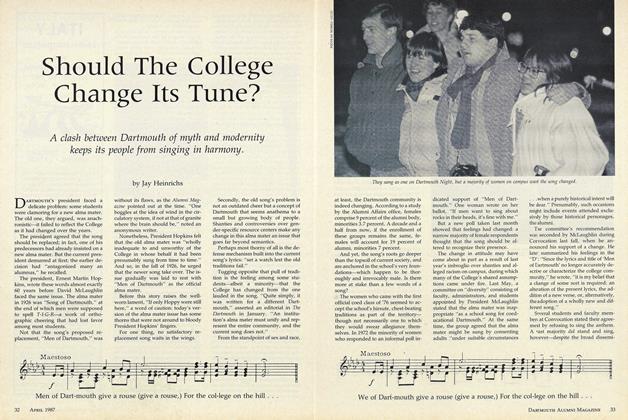

Cover StoryShould The College Change Its Tune?

APRIL • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeaturePersonal History

May/June 2010 By JOE BABCOCK ’08