Budd Schulberg '36. Garden City, N. Y.:Doubleday and Co., 1972. 203 pp. $5.95.

No doubt about it. In The Four Seasons ofSuccess Budd Schulberg has got it all together. The novelist's eye for character, plot, significant vignette; the playwright's ineffable feeling for the irony, the tragic comedy, of the human condition; the critic's attention to logic, tone, proportion; the craftsman's concern for well honed, lucid prose: Schulberg's versatile talents all come to focus in this book, and they all cohere.

The book is "about" writers—specifically, modern American writers—and their craft. Its subtitle announces the subject clearly enough: "Personal Reminiscences about John Steinbeck, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, William Saroyan, Thomas Heggen, and Nathanael West," all of whom Schulberg knew well. But why precisely these six? Why no extended treatment of any one of the myriad other literary contemporaries whom he also knew intimately? Because The Four Seasons is not just a random pot pourri of "personal reminiscences" about the literary great and near great, but rather a searching examination of the causes of literary success and failure in contemporary America. And each of these six writers embodies one aspect or another of the tragic paradox of failure in success. "Failed success," Schulberg calls it: that is his real subject.

Why. the book asks, is literary success in America so ephemeral? Why is the writer's garland more often than not, as the poet says, briefer than a girl's? Why does the abyss of failure habitually lurk just barely beyond the pinnacle of success? Whence the paradox of "failed success"? Why, and—Schulberg adds—why so soon?

The question has no answer for literalists, even literalists of the imagination. For, at bottom, beyond Schulberg's self-imposed temporal and literary limits, it evokes again the universal paradox at the heart of all tragedy: why the almost fated fall at the very summit of the protagonist's powers? But if the question is literally unanswerable it has always been artistically demonstrable. Thence a significant body of our major literature. Sophocles and Shakespeare dramatized it, Aristotle pondered it, Milton poeticized it, Hardy novelized it. "As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods,/They kill us for their sport," cries Shakespeare's Gloucester. No, answers Kent, "it is the stars,/The stars above us, govern our conditions." On the contrary, concludes the philosopher Novalis, "Character is fate." The question abides the answers: why the fall at the instant of greatness? Why "failed success"?

Schulberg comes down on the side of the stars—and stripes. Failed success is as American as apple pie. Our writers are victimized by our national compulsion to judge quantitatively, to rate all aspects of life, even literary achievement, on a scale of one to ten. As with our football teams, so with our writers; we must have a Number One. And thus arises the insidious syndrome, "the Number-One-ism that changes literature to bookbiz."

A harmless enough game, one would suppose, this national compulsion to play literary king-of-the-hill. But not so, not so at all, Schulberg argues. Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Saroyan, Lewis, West, Heggen: each painfully demonstrates, each in his own season, Schulberg's thesis that the effect of the Number One syndrome on the writer is ruinous, the more so if, like Hemingway, he consents to play the game himself. Though art is long, talent is fragile, and when the writer, having achieved initial success, begins to think of himself "not as a good mountain range of a writer, but as 'Number One,' like Texas in football, U.C.L.A. in basketball, ... then that big number is in big 'trouble." His very success—his uniquely American success—has spawned its own failure, for he must then compete "not only with the best he [has] to offer (which is the positive form of artistic competition) but with the image each one [has] created or [has] encouraged the public to create for him."

Inexorably then "the attrition of success" sets in. The worm gnaws at the vitals of the writer's art. Season succeeds season. The spring of his accession lives only as distant memory; autumn's frost touches summer's bloom; the winter winds of public neglect finally congeal and freeze his cold bare ruined talent.

Schulberg's thesis is as melancholy as the roster demonstrating its validity; Melville, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Saroyan, Lewis.... Fortunately, it is not unrelieved. For in literary fashion as in nature the inscrutable vagaries of the gods now and then decree a rebirth; the winter winds occasionally relent, and there occurs, Schulberg observes, that "second spring, the second coming, when the bulb buried in the ground ... bursts forth again in glorious reaffirmation like tulips and daffodils. The second spring of Herman Melville and Scott Fitzgerald and the posthumous first spring of Nathaniel West."

Mr. Ross, a specialist in modern Britishliterature, is Professor of English at BowlingGreen University in Ohio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

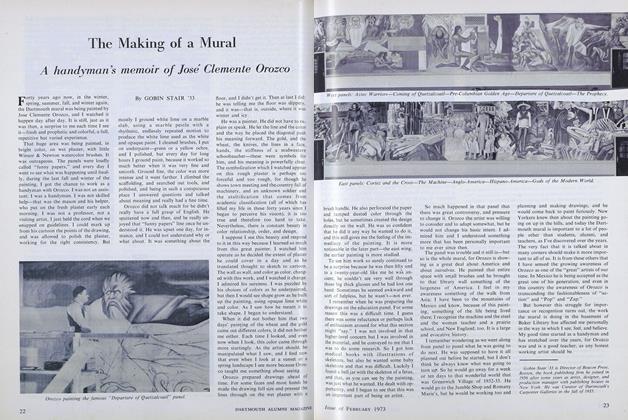

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

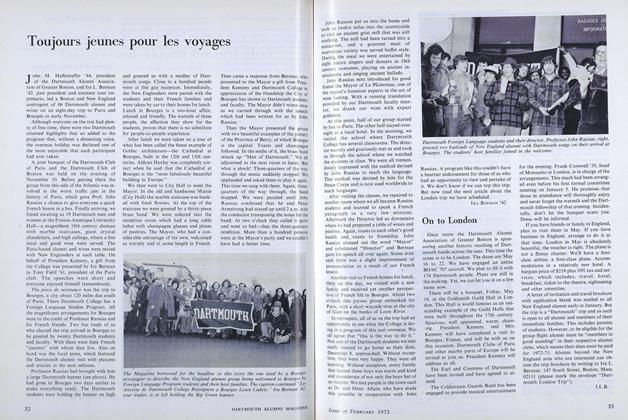

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksFRANK PEARCE STURM. HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND COLLECTED WORK.

OCTOBER 1969 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Article

ArticleSteel and Crinoline

May 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFundaments

June 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksPassable

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1921 -

Books

BooksEDITOR'S PICKS

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 -

Books

BooksTHE WALDENSES IN THE NEW WORLD

June 1942 By A. Howard Meneely -

Books

BooksSPACECRAFT AND MISSILES OF THE WORLD, 1962.

July 1962 By HOWARD F. EATON, CAPT., U.S.A.F. -

Books

BooksPlanetary Village

MARCH 1982 By T. S. K. Scott-Craig -

Books

BooksUNIVERSAL CONSCRIPTION FOR ESSENTIAL SERVICE

November 1951 By Virginia L. Close