WRITING THAT WORKSby Kenneth Roman '52and Joel RaphaelsonHarper & Row, 1981. 105 pp. $9.95

Two years ago in this section of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE we had occasion to commend a recently published booklet written by Kenneth Roman '52 and Joel Raphaelson and entitled simply How toWrite Better. It was, we said, a short, lively little manual, a modest 57 pages in length, untechnical, witty, down-to-earth practical. Its aims were confined to showing business executives how to write effective reports, memos, and letters.

For all its self-imposed limitations, however, the little book had the ring of authority. As executives themselves in a major national advertising agency, Roman and Raphaelson clearly knew most of what there is to know about the uses and abuses of language. Now, in Writingthat works, they have expanded the scope of their original booklet to include guidelines to the whole range of business writing.

In the essentials little seems changed. At the heart of the new manual, as of the old, is a superb chapter containing a series of 17 do's and don't's ("principles of effective writing," the authors call them). For instance: "Don't mumble. Once you've decided what you want to say, come right out and say it"; "Make your writingvigorous, direct-and personal" "Useshort paragraphs, short sentences-andshort words"-,or-here is a first principle indeed!-" Write simply and naturally the way you talk."

The major emphasis of the book, moreover, is still on writing effective reports, memos, and letters, but there are major additions that significantly increase both the scope and usefulness of the new book: chapters on how to write effective directsales letters and fund-raising appeals ("How to get people to give you money," the authors succinctly call it), on principles of effective speech-writing as well as other kinds of oral presentations, and on the allimportant re'sume'.

Roman and Raphaelson know all the devices of the writing craft. But they also know something a good deal more nearly basic about good writing: At bottom it is not a trick of grammar, nor does it result from mere linguistic or syntactical manipulation. Clear writing demands first clear thinking. On that crucial point Roman and Raphaelson quote a well-known authority: "Most people 'write badly because they cannot think clearly,' observed H. L. Mencken. The reason they cannot think clearly, he went on, is that 'they lack the brains.' " This book cannot, of course, supply the brains, but "it follows," as the authors say, "that if you can think clearly, you have a fighting chance of being able to write well."

Writing that works belongs on every executive's desk; it's a simple matter of enlightened self-interest. Roman and Raphaelson's argument is persuasive: "The only way some people know you is through your writing. ... To these women and men your writing is you. It reveals how your mind works. Is it forceful or fatuous, deft or clumsy, crisp or soggy? When your reader doesn't know you, he judges you from the evidence in your writing."

R. H. R

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

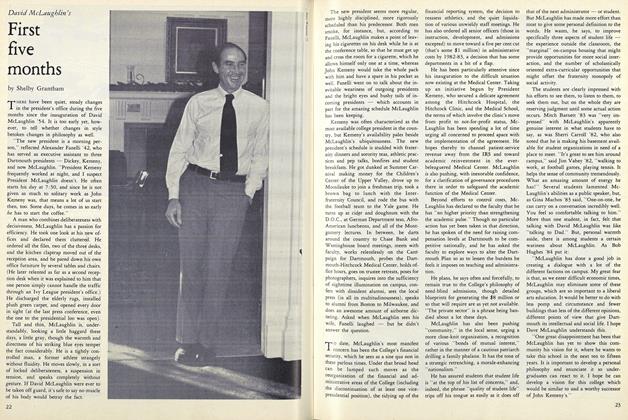

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

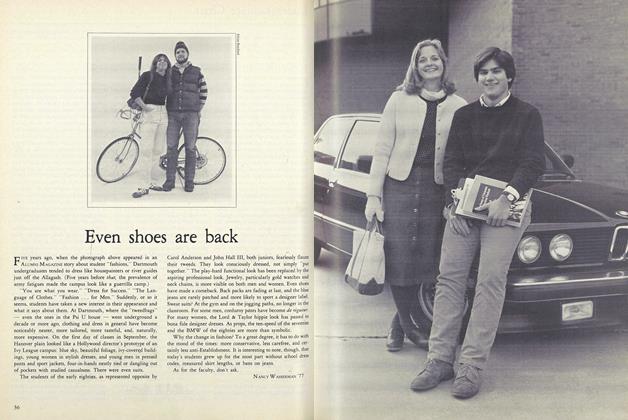

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

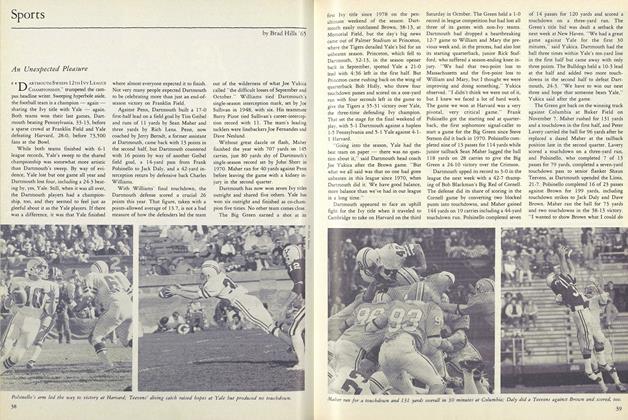

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Robert H. Ross '38

-

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksDRIFTWOOD: MAINE STORIES.

April 1974 By ROBERT H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksFacing the Great Issues

MARCH 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksMountain Man

October 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksGalaxies

November 1979 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksAlbert W. Levi '32, is the author

December 1933 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JULY 1970 -

Books

BooksTalking Sense

JAN./FEB. 1978 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksKate Sanborn, July 11, 1839 - July 9, 1917

November 1918 By J.K.L. -

Books

BooksTHE POETRY OF GREEK TRAGEDY.

July 1958 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LITERARY ANNUALS & GIFT BOOKS 1825-1865.

December 1936 By Oliver L. Lilley'3O