Fresh insight into that distinctive academic institution called tenure was provided recently to members of the Alumni Council by Jere R. Daniell II '55, Associate Professor of History and faculty representative on the Council.

He spoke to the issue, stressing he was reflecting only his own views, because the concept is currently under scrutiny in many universities around the country, including Dartmouth, where the faculty shortly will be considering an ad hoc study committee's report supporting academic tenure with some proposed modifications.

The response to Professor Daniell's remarks among Council members suggested that alumni in general might be interested in his analysis, particularly in view of acknowledgements by Council members after hearing his presentation that the issue is widely misunderstood outside academic circles.

"In a very real sense," Professor Daniell said, "the tenure system functions in a cruel way, particularly in a slow market where there are more qualified faculty than there are openings."

He explained that under the tenure system a young faculty member with the rank of assistant professor undergoes an "apprenticeship" of six, sometimes seven, years and then it is "up" to the rank of associate professor with tenure, or it is "out."

For that faculty member who is not promoted at the end of six years and who therefore does not make tenure. Professor Daniell explained, the "out" is quite literal. One-year terminal contracts are awarded young faculty who do not find a new position prior to the close of a second three-year contract, but under the system such extensions are unequivocably terminal.

"Unlike most professions, where an employe or an officer can top out at an intermediate level and still be retained, there is no middle ground in academe under the tenure system," Professor Daniell said. "It is 'up' or 'out,' and for many young scholars it is a cruel system which in some cases can be quite devastating."

Professor Daniell pointed out that the system was designed to protect academic freedom and that history had underlined the importance of such protection. If this is accepted, he said, the question becomes one of establishing when and under what circumstances tenure is granted.

Another argument for the tenure system cited by Professor Daniell is its role in maintaining quality within the long-term faculty. As harsh as it can be, the requirement that tenure for a junior faculty member be decided after about five years of observation gives the institution some basis for judgment and forces the institutions to make those difficult decisions within a specific time-frame, thus continually weeding out any weaker members.

The system has built into it some very real institutional, as well as individual, costs, he acknowledged, since the vicissitudes of timing and the limitations on the numbers who can be given tenure in any one year mean that sometimes very good men and women are denied tenure and forced to leave.

There's a subtle and growing sense of excitement among the Earth Sciences faculty, virtually all of whom are cooperating in probing new horizons in the wake of new concepts about how the great physical forces on and under the earth's surface are shaping our globe.

Symptomatic of this involvement is the role of Charles L. Drake, Professor of Earth Sciences and an authority on oceanography, marine geology and tectonics, the branch of geology concerned with earth .structures, especially folding and faulting.

Professor Drake is chairman of the U.S. Geodynamics Committee set up at the urging of the Geophysics Research Board and American Geophysics Union to plan and coordinate a iong-range program of solidearth studies to capitalize on what he called "revolutionary" findings on the structure of the earth and its dynamics. Seafloor spreading, reflected in the gradual widening of the Atlantic and the contraction of the Pacific Ocean, was suggested as a natural focal point for the program.

Similarly, because understanding of the phenomenon of earth movement requires data from around the world, an Interunion Commission on Geodynamics was established as an international coordinating body. And Professor Drake is president of that organization bringing together seven of the world's distinguished earth scientists for planning purposes.

Writing about the program in a summary report, Professor Drake cited the "extraordinary advances made during the past five years in our understanding of the origin of earthquakes, volcanism, faulting and mountain building - the basic processes which shape the surface of our planet."

He referred to the newly emerging concepts of sea-floor spreading, plate tectonics and global tectonics, by which the earth surface is perceived as a series of glacially moving plates, and said, "It would be difficult to overstate the success of these ideas in bringing together the different disciplines which constitute the earth sciences."

Thus, today, instead of working along separate tracks, micropaleontologists, geomagnetists, marine geomorphologists, and seismologists are all working together "to supply the crucial test of a concept comparable to that of the Bohr atom in its simplicity, elegance and ability to explain a wide range of diverse observations."

Reflecting the national trend toward cooperation among disciplines. Professor Drake stated that the Dartmouth earth sciences faculty are collaborating with a "new sense of cohesion perhaps rarely if ever enjoyed before." He cited as examples the work of Richard E. Stoiber '32, chairman of the department, on volcanoes in Central America and the relationship of their activity to earth tremors and quakes; Geophysicist Robert W. Decker, on measuring movements causing collisions and separation of ridges in Iceland; Paleontologist Gary D. Johnson on fossil stratification around Lake Rudoph in Africa; Geologist and Geomagnetist Noye M. Johnson'on correlating the records of fossil strata with magnetic reversals in both Pakistan and Arizona; Geologist John B. Lyons, on the Appalachian Mountain system, and Robert C. Reynolds on the clay minerology of the Colorado River.

Although working on different fields within earth sciences at locations around the world. Professor Drake emphasized they are also working together to see how individual projects relate to new concepts of how the earth shapes itself.

Dr. Helen L. Robinson, a specialist in cellular and development biology, has been named the first holder of the Gross Taylor and Cornelia Pierce Williams Assistant Professorship in Biology at Dartmouth College.

Dr Robinson who will hold the chair until June 30, 1975, is the first woman faculty member to be named to an endowed chair at Dartmouth College.

The Gross Taylor and Cornelia Pierce Williams chair also is the first of its kind for assistant professors at Dartmouth. It was established by Dr. and Mrs. Robert P. Williams '42 of Houston, Texas. Dr. Williams is professor of microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and the professorship is named in memory of his parents.

The endowed chair is intended to give encouragement and recognition to outstanding young teacher-scholars at Dartmouth during the early years of their careers and is to be awarded every four years to an assistant professor in biology.

Dr. Robinson joined the Dartmouth faculty in July 1972. A graduate of Bryn Mawr College, she was awarded her Ph.D. degree from Yale in 1971. She spent one year in post-doctoral research at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. She is currently conducting research on the biochemical aspects of amphibian metamorphosis.

Dr. Robert E. Gosselin, chairman of the Department of Pharmacology at Dartmouth and an authority on poisons and pollution, recently demonstrated a novel computer program which assists medical students to recognize and classify some 300 drugs by their official and generic names.

The computerized drill program, Designed and written by graduate students and faculty in Dr. Gosselin's department for use by medical students studying pharmacology, was presented as a special feature at the national conference of the Association for Medical School Pharmacology in Sarasota in January.

Dr. Gosselin said the drill program asks students to identify and classify 300 drugs in 124 different classes. The various drugs are randomly selected by the computer so that no two programs will be the same.

"Not only does this drill help ease the difficulty of recognizing drugs due to the large number of drugs known by various names, but it also helps the student build his medical vocabulary," Dr. Gosselin said. He added that the drill program is sophisticated enough to tell the student when he is right and also explain what class a drug belongs to when he is wrong.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

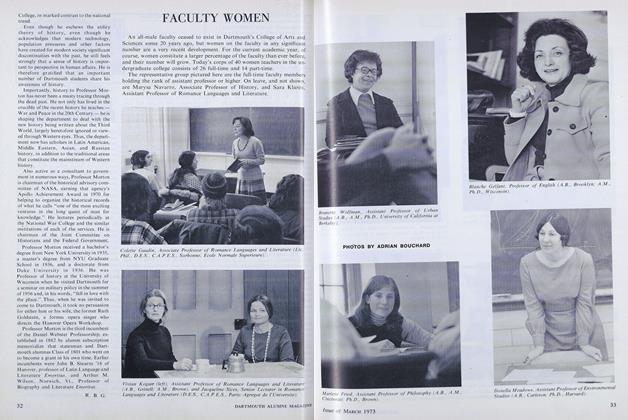

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73