Picture a cold Sunday evening at the Hop. From the basement, singers emerge as the Handel Society rehearsal comes to an end. They have been working on Bach's Magnificat. They pass a practice room where a trumpet noodles some jazz licks. By the stairs, in Buck Lounge, is a group of musicians playing bongo drums, guitar, reeds. Up several flights of stairs, outside Spaulding Auditorium, there is a crowd of people waiting to get into the Film Society's late showing of Werner Herzog's Every Man For Himself and God Against All, or Kaspar Hauser (Germany, 1975). It's an interesting slice of what's hopping at the Hop but notice, movies are up there at the top, while Bach is in the basement.

Bach will take care of himself.; What I'm going to talk about is the high position of movies at Dartmouth. And; I want to get at what is special here hot our. very competent audio-visual services or our television studios or our film society, because most campuses have these things. Rather, it is the way that movies-shadows on the wall-can serve as texts that interests me.

I hasten to add that I am not talking about filmed novels or plays, or documentaries for the social sciences. Nor am I defining a movie as the next best thing beyond Classic Comics on the way towards a good book. Critic Pauline Kael has spoken sharply on the subject: "As we are all aware, colleges love to justify showing movies for fun and profit by referring to them as classics and masterpieces. Whenever possible, discourage this practice." There may be film classics, of course, but to hasten to sort them out that way is to treat them too much like books, which already struggle under the handicap of being over-studied and over-prescribed, if not altogether smothered by the bureaucracy of intellect. No, I like the sense in which a movie can be a text without being labeled as one.

If a text is something we like to read and then talk to others about, movies have the advantage of being the most naturally available of any medium we have that is associated with ideas. Ask most students what they think about a poem by Stevens, a novel by Bellow, or a play by Williams, and their reply cannot quite avoid taking on some tones of the classroom, the diction of recitation, the self-consciousness of academic exchange. But ask them how they liked Star Trek II or the latest Woody Allen, and they will express forceful opinions, unpremeditated, from the centers of their beings.

Having strong, unaffected opinions does not automatically take one into the realm of civilized discourse, to be sure. Nor does calling every other film "great" or "awesome" demonstrate much of a concern for ideas. But at least the starting point is from strong feelings, helped by the sense that one is not constrained to follow pre-approved approaches or to defer to one's elders. And I have found that many students can be counted on to convert those initial passions and curiosities into something more sustained and precise as they go from text to text, collecting and making distinctions.

Let me illustrate. Here is a list of 50 film titles I gave my seminar in film criticism at the start of the course, to find out what they already knew. How many of them have you seen? The African Queen, AllAbout Eve, Alphaville, Beauty and the Beast,Belle de Jour, Birth of a Nation, Blow Up,Bonnie and Clyde, Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,Casablanca, Children of. Paradise, CitizenKane, Dolce Vita, 8½, Fantasia, The General, Gold Diggers of 1933, The Gold Rush,The Graduate, High Noon, Jules and Jim,Little Caesar, Magnificent Ambersons, Maltese Falcon, Nashville, The Navigator, Ninotchka, North by Northeast, Nosferatu, ItHappened One Night, Open City, Potemkin,Psycho, Rashomon, Red River, Shane, Rules ofthe Game, The Seventh Seal, Singin' in theRain, Some Like It Hot, Star Wars, LaStrada, Sunset Boulevard, The Third Man,2001, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Weekend, Wild Child, Wild Strawberries, YellowSubmarine.

All twelve of my seminar members had seen Casablanca, The Graduate, and StarWars, which is about what I'd suspect for citizens of the popular culture who also take in "campus cult" pictures. Most of them had also seen The African Queen, Bonnie and Clyde, Citizen Kane, Nashville',North by Northeast, and Singiri in the Rain. The Hepburn/Bogart movie, along with the Orson Welles and the Alfred Hitchcock, suggest this class had a certain number who had some rudiments of film history in their backgrounds; on the other hand, the fact that few, or none, had seen Godard's Alphaville or Weekend, or Bunuel's Belle de Jour, or Carne's Children ofParadise, or Welles' Ambersons, or Keaton's Navigator, or Rosselini's Open City, or Hawks' Red River, or Bergman's WildStrawberries, suggested that there was a lot left to see, connect, and talk about.

To start with, anyone who loves movies wants to invite others to stretch out their viewing range. It doesn't take a solemn lecture on film history or aesthetics to recommend that a person who liked Kane would find Ambersons intriguing, or that someone who laughed at Chaplin's TheGold Rush (which half the class had seen) might laugh even harder at Keaton's TheNavigator. Not to know Keaton! We hasten to the projection room, aware that future talk must include Langdon and Lloyd; and then compare silent comedians with those in sound.

On the other hand, not to know the pioneer work of Italian neo-realism is to miss the point of Fellini's personal development, so Open City and La Dolce Vita can be played off against each other. And this will surely require us to ask just what "realism" in cinema means, since most presume the camera's eye literally reproduces what is in front of it. If so, what to make of an enchanted fable like Beauty andthe Beast (which half the class had seen)? Its author, Jean Cocteau, quotes Goethe, "Truth and reality contradict each other," and observes, "In films a trick shot is often much more convincing than the real thing, and besides, it gives reality some relief.

And so it goes. Discussion of Birth of aNation will inevitably provoke the question as to why silent melodrama seems to be so much harder to watch today than silent comedy. And then we can compare another culture's melodrama, the littleknown Rashomon by the Japanese master, Akira Kurosawa, along with the Swedish Wild Strawberries by Bergman.

These are texts like mirrors, or crystal facets: the more we look, the more reflections we see, the more angles of vision we can follow from one thing to something new. If we take Shane (which half the class had seen), we must consider the fact that the form of the western is already here highly stylized and mannered, which will lead us back to Ford's Stagecoach, or across to Red River, and forward to Altman's McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Kurosawa's Yojimbo, and even Lucas's The Empire StrikesBack.

Also, because film is a late development out of narrative media, it is highly synthetic; so that almost any inquiry into connections or backgrounds leads one into other fields and other arts-to Civil War history, to Owen Wister's novel, The Virginian, to the art of Remington, or Turner's thesis concerning the American frontier. So if film begins by making few demands on the viewer, it very quickly brings one who is attentive into new territory, where trails crisscross every which way and disappear from sight.

I remember seeing a filler in a newspaper once that described a "47-year-old widow in Wales" who had seen The Soundof Music 500 times and had announced an ambition to see it 500 times more. Just possibly, such a person could make one text her whole university, but I doubt it. My students find that they are driven continually to set one text against another: incomparisons begins higher education. From matching this against that, a personal, yet tough-minded, sense of Good, Better, Best begins to emerge. Against Sound ofMusic, why not the sprightlier Mary Poppins? Or perhaps Cabaret will be offered up as overwhelming contrast; and then someone might say he or she liked Julie Andrews better in 10 than in any number of "nice-girl" softies.

For this process of sorting through the texts that movies make, we have a model in that self-proclaimed "amateur" James Agee. When he began to write reviews for The Nation in 1942, he spoke of the prevalence of movies he described as "high-mediocre, ...hollows filled with persuasive shadows and echoes." You see him, then, presuming to make distinctions among the shadows:

"This reverent and just evaluation of kitsch takes the place of that depth of heart and mind from which a first-rate artist works; and taste, tricks, detail, a dancer's delight in form, are the deft and of themselves respectable substitutes for a firstrate artist's perfecting of his perception. The result is that it is almost too elegantly geared for almost too many 'effects.' It has been so subtly used by the fingertips, rather than born out of the whole of the body, that discriminating watchers, in turn, are liable to find it merely touching, and pleasing to touch, whereas the undiscriminating watcher, taking this delicate imitation of power for power itself, is subtly hornswoggled."

Not the least of the appeal of this kind of writing is its range, where complex thoughts are captured elegantly, yet wind up at the pungent and homely word, "hornswoggled." My students, too, as regular consumers of cinematic texts, don't like to be hornswoggled. And as they work harder and harder to explain why they feel what they feel about what they have seen, their language becomes more and more quotable.

I have in mind one reviewer's attack on Jaws, in which, she said, "the people are as plastic and fake as the much-celebrated shark nicknamed 'Bruce.' " She then went on to say, "for a film to be considered 'good,' I would argue that its range of meaning be imaginative and compelling, so that some new knowledge about the human condition is gained." That's asking "the most" from the movies.

And she capped her review with this zinger: "To borrow a line from Quint, the film has 'dead eyes': it only comes to life when it bites you."

I think James A gee would have enjoyed that. I certainly did, because it marked so well a stage in that progress from general excitement to the refinement of the senses, and from feelings to thought that marks the best kind of education we can receive from texts, whether they lie in our hands or flicker on the wall.

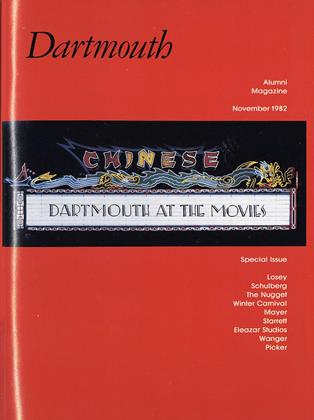

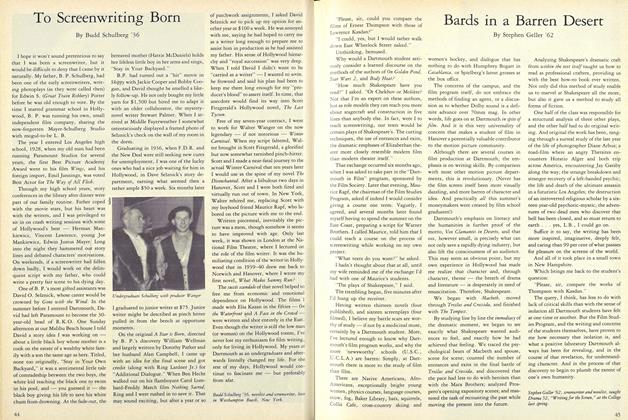

A Gay lord quiz: What thematic and generic elements connect Mifune (left) with

Wayne (right)?And, while you're at it, name the movies and their directors.

Alan Gay lord chairs the Department of English at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

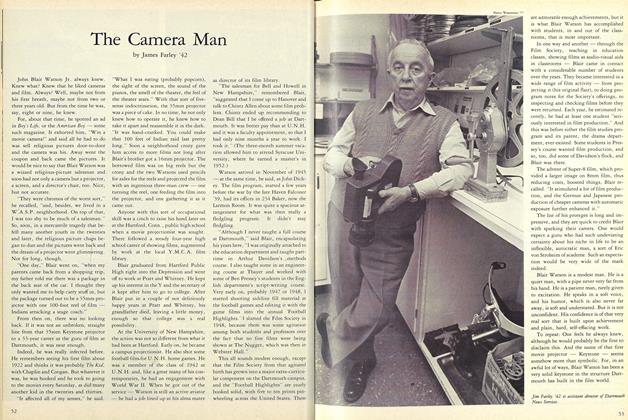

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

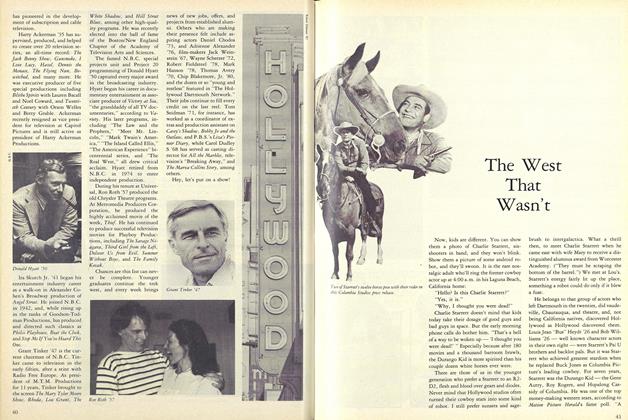

FeatureThe West That Wasn't

November 1982 By R.E. -

Feature

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWebster in the Raw

NOVEMBER 1999 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CHOOSE A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By BARBARA MURPHY '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Cover Story

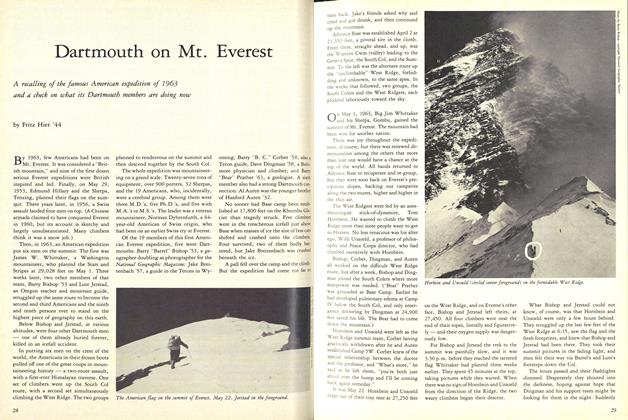

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mt. Everest

MAY 1983 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham