The young man who occupied room No. 20 Wentworth Hall, and who took his board in the neighborhood at Miss Murphy's for 11 shillings a week, was no ordinary Dartmouth student in the fall of 1839. His face bore marks of strong character; his features were rough-hewn and rugged, with high cheek bones, and his nose was distinctly aquiline. He was now in his senior year, and he had come a long way from his modest beginnings at his home in western New York. For few Indians in his day had ever gone to college, and even fewer had gone to Dartmouth. The man was Maris Bryant Pierce, a Seneca chief, whose Indian name, Ha-dya-no-doh, or Swift Runner, was that given him at the Allegany [sic] Reservation where he was born in 1811.

Pierce had been born, however, in a turbulent age in which the Senecas had progressively lost their homeland, piece by piece. The Sullivan expedition during the American Revolution had destroyed most of the Seneca settlements in the Genesee country and had driven the Senecas farther west north west to Niagara and other areas of western New York. After the war, white pressures on Indian lands increased, and by 1797, the Senecas had given up all lands east of the Genesee. In the same year, unscrupulous white negotiators, led by Robert Morris, a financier of the American Revolution, pressured and induced the Senecas to sign the Treaty of Big Tree, whereby the Nation was deprived of all remaining lands in western New York. Morris had held pre-emptive rights (the legal right of first purchase) to these lands, some 200,000 acres, for which he paid the sum of $100.000 At the same time, the Senecas were forced onto eleven reservations which historian Anthony Wallace aptly termed "slums.in the wilderness."

Yet Maris Pierce as a young boy had attended a Quaker school adjacent to the Allegany Reservation, and later spent two years at Fredonia Academy. His early education continued at another academy in Homer, Cortland County, after which he spent some time in Rochester, where he was converted to Christianity by the Presbyterian Church. His pre-college studies ended in a school located in Thetford, Vermont, following which he was admitted to Dartmouth College. During these early educational years, however, the Pierce family moved closer to Buffalo, and the Buffalo Creek Reservation, or Dyosyowan, some five miles from the city, came to be regarded by Pierce as his home until its abandonment in 1845.

Pierce's conversion to Christianity doubtless attracted the attention of evangelical missionary societies, for Pierce, at the age of 25, was sponsored by the Society in Scotland for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge to enter Dartmouth College in 1836. This evangelical Christian society had been founded in 1709 by Scotch Presbyterians, and had had brief missions among Mohawks, Oneidas, and Delawares of New Jersey throughout the 18th century. By 1800, their mission work included some Senecas. Part of the rationale of the Society for sending Pierce to Dartmouth may have come from their belief that Indians as missionaries might succeed among their own people, where whites had failed. However this may be, it is Pierce's years at Dartmouth that form the substance of this article. There a promising young Seneca from western New York was about to enter a white institution of higher learning.

Pierce, however, was not the first Native American to enter college in New Hampshire; Reverend John Sergeant had established an all-Indian school at Housatonic in 1748, followed by Eleazar Wheelock's school in 1754. But Wheelock believed that Indians should associate with English youths in a mixed school, and should be removed entirely from native influences. From this school, later named Moor's Indian Charity School in honor of its benefactor, eventually emerged Dartmouth College. As president, Wheelock's first draft of its charter indicated that Dartmouth was being founded to educate "Youth of the English, and also the Indian tribes in this land in reading, writing, and all . . . liberal Arts and Sciences." But educating English youths remained a subordinate purpose in his educational plans; Wheelock hoped to attract large numbers of Indians to the new institution, yet he proceeded to operate a liberal arts college that graduated Only three Indians in the 18th century and eight in the 19th.

Pierce's enrollment at Dartmouth in 1836 must have marked a rather drastic arid perhaps traumatic change in his way of life and daily routine. First years in college are often difficult under the best of circumstances; Pierce found himself in an environment quite different from that in which he had received his early white education, and the Dartmouth academic calendar at this time far different from today's may have proven baffling even to whites inured to the complexities of non-Indian civilization.

At this time, and throughout the presidency of Rev. Nathan Lord (1828- 63), the following college calendar prevailed. The fall term began about September 1, and ran until November 25; this was followed by a seven weeks' vacation (until about January 24), after which a winter term of seven weeks began. During this period, those students teaching were not required to attend. The spring term started about March 21, and this lasted until Commencement, the last Wednesday in July. The spring session was punctuated, however, by a two-weeks' vacation in May. After Commencement, a fourweeks' vacation ensued until the beginning of the new fall term. The structure of this academic calendar worked, nevertheless, to Pierce's advantage, for it allowed him time away from campus in which he popularized and advanced the cause of the Six Nations, particularly the Senecas, with white audiences. It also permitted him to go on occasion to Washington to work for legislation beneficial to his people. The first order of business for Pierce, however, was academic work.

In his first two years he took courses designated as Languages and Mathematics, yet Pierce himself refers to having attended daily lectures in minerology and chemistry accompanied by experiments. Perhaps his interest in minerology was stimulated by the oil reserves, long used by Senecas for medicinal purposes; these were located on the Oil Spring tract, just north of the Allegany Reservation. Other classes attended consisted of anatomy, and lectures on drugs (opium) and alcoholic intoxication. Yet studies in the humanities and physical sciences and biological sciences did not preclude work in the social sciences, for Pierce reports having studied Jean-Baptiste Say's Political Economy.

During Pierce's years at Dartmouth, the marking system was based on a scale of one to five one representing the highest achievement. His transcript for his freshman year indicates a rather pedestrian performance, yet this may be owing to the necessary adjustments to college life and routine; some improvement was made in his sophomore year which he ended with a 2.8 average. In any event, his two final years in college were marked by much better academic work, and President Lord remarked that Pierce "... had finished his course in college very honorably." Elsewhere, Lord described Pierce as "intelligent, pious, stable, and a good scholar." John Tawse, Secretary to the Scotch Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, was also pleased with Pierce's college work, and observed that he "is altogether as interesting a young man as ever I saw, and I trust from his talents, his sound principles, and the knowledge he has acquired, he will prove a great blessing to the Nation of Indians to which he belongs...."

While studies occupied much of his time, still Pierce found opportunity for recreation, as have many generations of college students. In the late 1830s, diversions at Dartmouth often consisted of forays into the countryside and picnics in the surrounding areas. On one such occasion, a group of young men and women, including Pierce, visited Enfield, New Hampshire, where a Quaker village was located. A picnic, refreshments, and boating on Mascoma Lake occupied the group on this excursion, during which Pierce remarked that he had had a "jolly time." He had been accompanied on this outing by a Miss Thompson, whom he described as "lively and agreeable," though he had not expected to have an especially good time. Still the group had been sociable and had shown "good sense," and nothing unpleasant had been said during the outing. Yet Pierce followed this statement with the remark that

"there was something [unpleasant] said which might as well or better not to have been spoken," but he does not elaborate upon it. It leads one to conjecture that perhaps some derogatory remark had been made concerning the "savage Indian."

On another occasion, the Dartmouth College phalanx, a primitive sort of ROTC, held muster on the green, and Pierce carried the standard, as he had done the previous year. The group proceeded to Norwich, Vermont, where they saluted one Captain Partridge, who made a short speech and treated the company to a glass of wine.

As Pierce's senior year drew to a close, graduating seniors were assigned topics on which they were to speak at Commencement; understandably, Pierce's topic was "The Destiny of the Aborigines of America," a subject in which he expressed great interest. Unfortunately, there is no record of what Pierce said at Commencement, but there is ample evidence that his years at Dartmouth were filled with a concern for the fate of the Seneca Nation, that of the Six Nations, and for that matter, the future of all Native Americans.

While erosion of Seneca lands had begun with the Treaty of Big Tree in 1797, it was during Pierce's sophomore-junior years that the infamous Treaty of Buffalo Creek was signed between the Ogden Land Company and the Senecas. In 1810, the Holland Land Company, which had eventually bought Morris' land holdings, had sold the pre-emptive rights to the Seneca reservations to the Ogden Land Company, and pressure was now brought on New York Indians to sell their reservations. As early as 1826, the Senecas had sold all five of the Genesee reservations, most of Tonawanda, about one-third of Buffalo Creek, and one fifth of Cattaraugus. During the next 12 years, further pressure was brought on the Senecas to induce them to vacate their reservations and to remove west of the Mississippi to lands in Kansas. Through bribes, threats, and misrepresentation, the Senecas signed the Treaty of Buffalo Creek in 1838, an agreement which stipulated that they leave their reservations and emigrate to Kansas. Yet because of widespread opposition to the treaty by Senecas, Quakers, and others, it was renegotiated in 1842, and the Senecas were allowed to retain Cattaraugus, Allegany, and what remained of Tonawanda reservations.

So it is easily understood that Pierce, at Dartmouth during the negotiations which led to the Treaty of Buffalo Creek, must have been tremendously upset and disturbed at the proceedings underway in western New York. His Nation and his home were threatened with removal and possible destruction. Accordingly, he undertook to make known to whites, wherever possible, the culture and achievements of the Six Nations, and to gain white sympathy for the Native American.

The flexibility of the Dartmouth calendar provided him with the needed time to accept speaking engagements. Probably the most notable speech Pierce delivered was to a large, enthusiastic crowd at the Baptist Church of Buffalo on August 28, 1838. He had returned to western New York before the beginning of his junior year, and used the occasion to gain an eloquent address on behalf of the American Indian and the Seneca Nation in particular. It is the only speech Pierce made which appeared in printed form and has survived to the present day. *

The first portion of Pierce's address was devoted to a detailed exposition of the cultural and social achievements of the Native Americans, thereby attempting to counter white criticism which stressed the belief that the Indian was incapable of either understanding or accepting the social and cultural values of a "higher," more civilized white society. In the latter part of his speech, he dealt with the question of Indian removal to the trans-Mississippi west, a move he strongly opposed. He concluded his memorable remarks with an appeal to the dictates of common sense and common honesty, and asked "on behalf of the New York Indians and myself, that our white brethren will not urge us to do that which justice, humanity, religion not only do not require but condemn." Yet as is often the case, those who should have heard Pierce's arguments and appeal were not there to hear them; it is unlikely that any manipulator of the Ogden Land Company was in the audience of the Buffalo Baptist Church that night.

Yet sizeable opposition by Senecas and segments of whites to the Treaty of Buffalo Creek continued, and Pierce, in his two remaining years at Dartmouth, did his utmost to win white support for the cause of the Senecas. Other gatherings were addressed at Parsippany, New Jersey, where he spoke to a large, interested, and enthusiastic audience in March, 1840. There Pierce explained the Six Nations to the church congregation, and spoke of their manners and customs. He also displayed Indian handicrafts which included wampum, moccasins, wallets, and work bags for women. He did this in an effort to disprove the frequent claim made by white historians that Indian women were indolent. Indeed, on an earlier occasion, Pierce had argued with a college chum over women's rights, which he strongly upheld: "It is my sincere belief that the rights of women should be sacredly kept and freely exercised by them, but I do not agree with them acting in the same capacity with men." Could he have possibly have read Rousseau's Essay onInequality?

Pierce found other occasions to popularize the cause of the Senecas and others of the Six Nations. Early in May 1840, he delivered a lecture to the citizens of Woodstock, Vermont on the ancient Iroquois Confederacy, in which he discussed their habits, customs, religion, and festivals. Not long before Commencement, Pierce also spoke to the Philomatheon Society at Meriden Academy on much the same subject; his hope was that it might help whites arouse themselves from their lethargy and look at the wrongs committed against his people. But days at Dartmouth were growing short.

As Commencement approached, Pierce was occupied with graduation activities, but a sense of sadness overcame him as he observed members of the senior class of 80 prepare to leave for their homes.

Where shall I go, [he asked himself,] where is my home, that I can call it my own? To the West? No where I was born. [?] Shall it be my native home and remain inviolate? I hope it was so, but also, it is not so. Our people are in the state of a great dilemma to go or stay but must go, says the government of the U.S. Humanity speaks: they may stay. They ought to enjoy the home of their fathers.

Leaving Dartmouth for the last time, Pierce started in mid-August for Buffalo Creek Reservation, where he arrived after a trip of four days which took him through Rutland, Albany, and Rochester. Once returned to the reservation, Pierce and other Seneca chiefs undertook to deal with problems arising from incursions on Seneca lands by the Ogden Land Company.

While Dartmouth had given Pierce an education which better enabled him to deal with the avarice and rapacity of whites, he must have felt that further preparation was advisable to protect his people from continuing white assaults. For almost two years after his return to Buffalo Creek, he read law in the Buffalo offices of Tillinghast and Smith, following which he returned in 1842 to his Nation to assist them in the compromise treaty with the Ogden Land Company. In the following year, Pierce married Mary Jane Carroll, the daughter of a British army office, in Utica, New York; the newly married couple spent their first two years together at Buffalo Creek, and when this reserve was abandoned in 1845, they removed to Cattaraugus where they remained for the rest of their lives.

Pierce's later years were occupied with continued efforts not only to protect the rights of his people, but to promote the general welfare of his Natiorp As an interpreter and secretary for the Seneca Nation, he played an important part in dealing with such matters as Indian emigration, timber sales, and relations with both the Ogden Land Company and the Quakers. He also had a significant role in the Seneca political revolution of 1848, which brought the elective system to the Nation. Maris Pierce was also a strong advocate of education for both pagan and Christianized young Senecas that would fit them for useful work in life; he opposed the use of alcohol and attempted to Christianize his people so far as possible. And through his education and continued contacts with whites, he strove to create a better understanding by whites of his own people. Maris Pierce was an individual whose feet were planted in two cultures; he was eclectic in the sense that he chose that which was best in both worlds. He used his knowledge and his abilities to insure the continuation of both the Seneca Nation and its culture. If, in today's parlance, Pierce could be termed a student activist during his college days, his cause was a worthy and justifiable one. Dartmouth College has good reason to be proud of this Native American graduate a man who was a credit to his alma mater and a leader among his people.

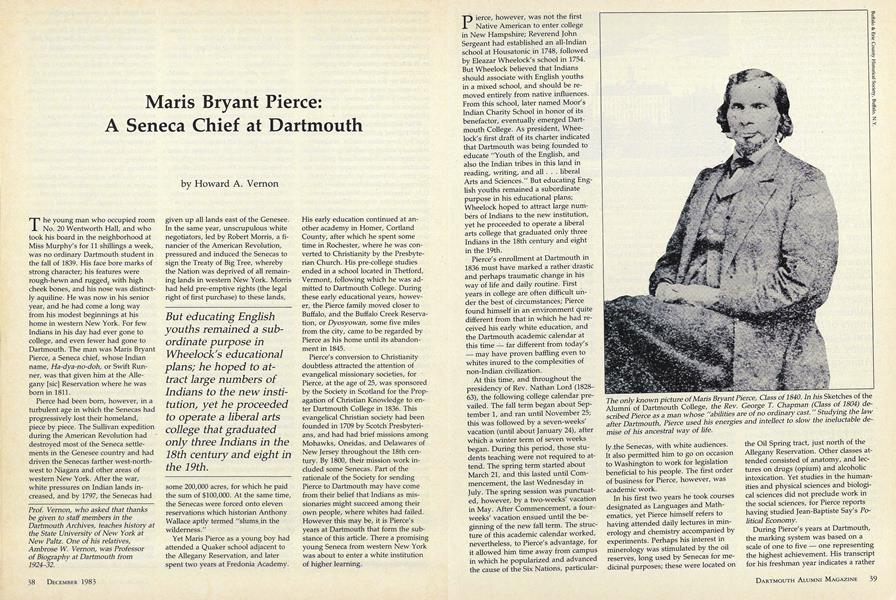

The only known picture of Maris Bryant Pierce, Class of 1840. In his Sketches; of the Alumni of Dartmouth College, the Rev. George T. Chapman (Class of 1804) described Pierce as a man whose "abilities are of no ordinary cast. Studying the lawafter Dartmouth, Pierce used his energies and intellect to slow the ineluctable demiseof his ancestral way of life.

Dartmouth Row in 1840, the year of Maris Pierce's graduation. The woodcut, whichis reproduced from the frontspiece of The Dartmouth, was executed by John SmithWoodman of Durham, a member of the Class of 1842. As the editors of The Dartmouth noted, "It is considered as correct a representation of the College as ever beenpublished."

Prof. Vernon, who asked that thanksbe given to staff members in theDartmouth Archives, teaches history atthe State University of New York atNew Paltz. One of his relatives,Ambrose W. Vernon, was Professorof Biography at Dartmouth from1924-32.

But educating Englishyouths remained a subordinate purpose inWheelock's educationalplans; he hoped to attract large numbers ofIndians to the new institution, yet he proceededto operate a liberal artscollege that graduatedonly three Indians in the18th century and eight inthe 19th.

His Nation and his homewere threatened with removal and possible destruction. Accordingly,Pierce undertook tomake known to whites,wherever possible, theculture and achievements of the Six Nations,and to gain white sympathy for the NativeAmerican.

Maris Pierce was an individual whose feet wereplanted in two cultures;he was eclectic in thesense that he chose thatwhich was best in bothworlds.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

December 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

December 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

December 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

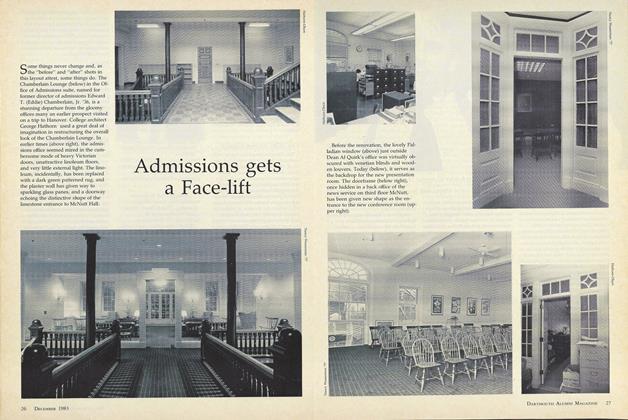

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

December 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

Sports

SportsSports

December 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Article

ArticleFlamboyant Rabbi

December 1983 By Laurie Kretchmar '84

Features

-

Feature

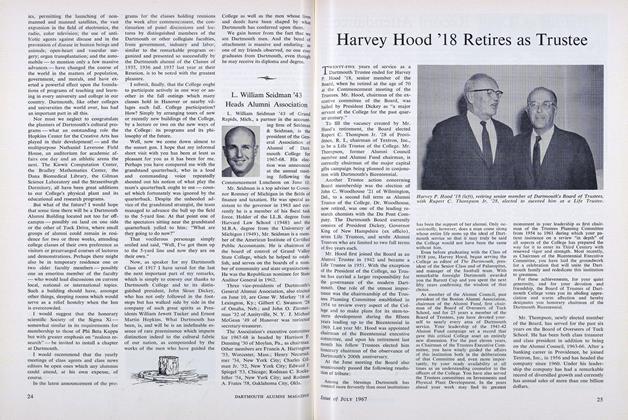

FeatureHarvey Hood '18 Retires as Trustee

JULY 1967 -

Feature

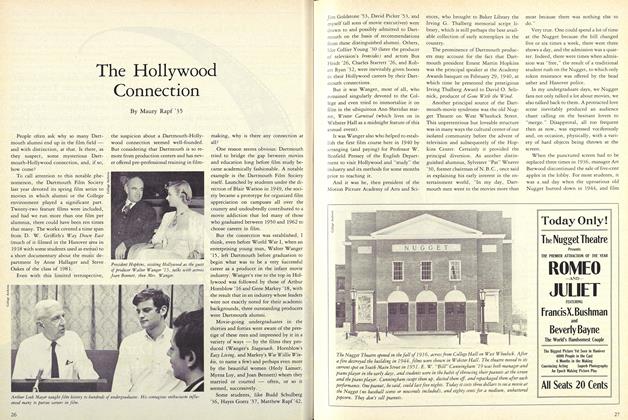

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2012 By Llewelynn Fletcher ’99 -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureOne on One

MARCH 2000 By Mel Allen -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO READ A POET

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT FROST -

Feature

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

DECEMBER 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD