"Architecture as a social and urban art in the very best sense," The New York Times calls it. "A symbol of the belief that human expressiveness has practical purpose," says The Christian Science Monitor.

Such is the lavish praise accorded the Arts for Living Center, designed by Lo-Yi CHAN '54 to bring together the performing and visual arts programs of New York's Henry Street Settlement House. An aesthetic triumph in itself, the building becomes part of the program. From the welcoming arc of its open plaza, with shallow steps echoing the front-stoop socializing of its traditionally immigrant, perennially poor, lower East Side neighborhood, to the colorful art displays clearly visible to the passerby, the Center beckons young and old to its lively melange of music and dance, film and drama, crafts, graphics, sculpture and painting. In an area where conflict is often the norm of schools and streets, ethnic diversity brings enrichment rather than clash to the Center, its fluid plan offering privacy with involvement, stimulating community pride and cross-fertilization of the arts.

The Arts for Living Center typifies the service-oriented structures that have won professional laurels for the young firm of Prentice and Chan, Ohlhausen and, for Chan, a 1972 community-service award from the JFK Library for Minorities. The partners have come to specialize in "buildings with a social basis" - public housing, civic centers, museums, libraries through a natural gravitation toward commissions for clients who share their values. "Any building inevitably reflects society, or it is doomed to failure," Chan points out. "We have found we can do better with buildings that contribute to society in meaningful and worthwhile ways." In the Arts for Living Center, for example, "we had everything going for us; the goals were strong and clear."

Born in China, Chan came to Hanover by way of Hawaii at the age of ten, when his father, Wing Tsit Chan, joined the Dartmouth faculty. He still recalls the culture shock, exemplified by the remarkable discovery that snow fell in flakes, not snowballs. In college, he took a modified art major with liberal infusions of engineering, working closely with Ted Hunter '38, a lasting influence even more in the realm of ideals than in techniques. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, Chan took his master's degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, interrupting the course for Army service.

Before striking out on his own, Chan worked for five years with I.M. Pei, "learning more than I had in graduate school." Architecture is best taught, he contends, by "the Typhoid Mary System" - exposing novices to experts and hoping the skill is infectious. "You can teach analysis in business school, for instance," he says, "but architecture is a synthesis, learned best through casework and problem-solving." Chan is familiar with both sides of the process, as a former part-time lecturer at Columbia's graduate school and visiting critic at Cornell.

While each architectural problem offers its own challenge whether it be the design of the Roosevelt Island-Manhattan tramway, a campus plan, a welfare center, an exurban residence, or a union vacation house or the renovation of an old factory for a community center - the greatest Chan has yet encountered is Hospice, an institution for the incurably ill. Still in design stage, in consultation with physicians and nurses from the Yale-New Haven medical complex, Hospice has as one purpose no less than "changing the attitude of society toward death." As people have lived longer to die of degenerative diseases and the small nuclear unit unequipped to care for the terminally ill has replaced the extended family, Chan suggests, the dying have been relegated to institutions which on the whole have served their needs badly. Even the medical profession, geared to cure, basically regards death as defeat, he adds; it can assuage pain, but may cope inadequately with patients in extremis and their families. In his design, Chan is trying to create an environment that adds dignity and meaning to the last of life. At Hospice, the four-bed wards with low partitions will provide privacy without isolation; the floor plan will be so arranged that immobile patients may find compensation through visual contact with activity; even their beds will be so oriented to windows that, seeing time in new perspective, they can better observe its daily passage. Dealing with the unavoidable paradox of dying as an integral part of living, Chan finds that "every answer brings a new question."

About such "rare talents" as his, a Dartmouth professor wrote in 1954, "... one hopes that they will be brought to fruition, and in some measure justify our work and our hopes." Chan's designs - living art for the art of living - surely justify those hopes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

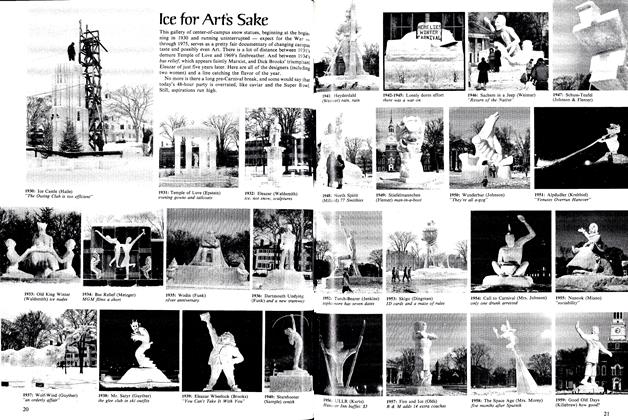

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Article

ArticleWinter Games

February 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

February 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

APRIL 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleFalling Dominoes

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMan in the Flying Machine

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

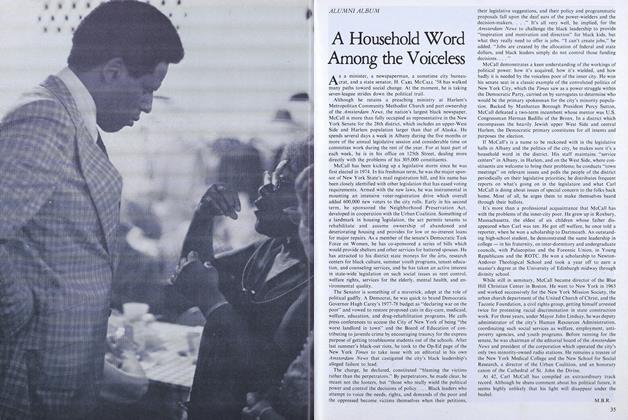

ArticleA Household Word Among the Voiceless

MAY 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R.