GIVE HARRY ACKERMAN '35 another half century, and he might qualify for the title of "grand old man of television." But for the nonce both he and the medium lack the credentials of age and time for such a patriarchal relationship. "Godfather" is out - connotation has all but removed that epithet from the lexicon of respectability. Perhaps "pappy of the sitcom" will have to do.

Judging from the misnamed "sneak previews" and the teasers that have assaulted our eyes and ears since mid-summer, this is to be television's "season of the sci-fi," featuring a clutch of latter-day Star Wars in electronic combat with other new shows blatantly derivative of what the moguls deemed the hottest item of last season.

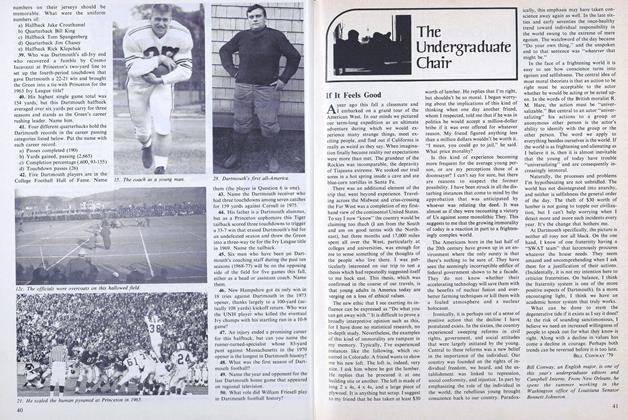

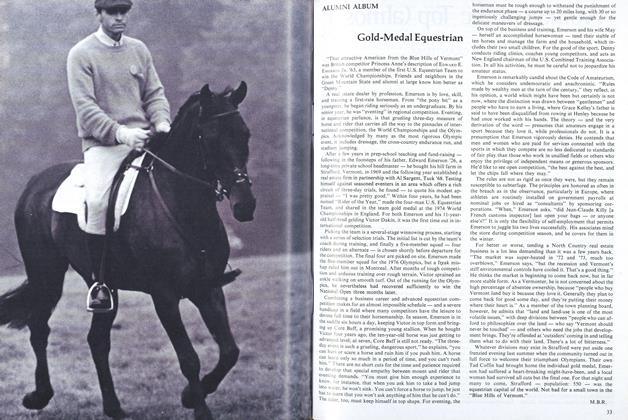

What will follow the space epics, the ethnics, the leering late-night soaps Ackerman declines to predict. "But what I think television needs," he says, "is a return to family-oriented situation comedies, in the vein of what Bewitched, The Flying Nun, and Hazel [front runners in the Ackerman stable] once represented." His wife Elinor Donahue, who played Robert Young's daughter on Father Knows Best (shown opposite with Ackerman in their Beverly Hills garden), has a new series called PleaseStand By, which he hopes may be "a bellwether in that direction."

Ackerman should know. His track record for picking winners is legend, and he has seen just about all there has been to see in the relatively brief history of the medium. Gunsmoke and Amos andAndy were his babies, on radio and TV; he has supervised the Jack Benny, Ed Wynn, Edgar Bergen, Donna Reed, and Paul Lynde Shows;, he has loved Lucy, been both Bewitched and Menaced by Dennis; he has accumulated a Sister Eileen, a Bachelor Father, and an Occasional Wife; he has "co-created" Love on a Rooftop, though not with The Farmer's Daughter. His mantel boasts two Emmies, and he has the unique honor of having been twice elected president of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences - an achievement )ie cherishes above the academy's awards. No other producer has been singled out for the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters cup. He holds the all-time record for series hands-down, having developed 20 in all, seven of which were on the air contemporaneously.

A number of notable specials - among them, Blithe Spirit, ABell for Adano, The Caine Mutiny Court Martial - have borne the Ackerman stamp, but the series are where his heart is. His personal favorites are Bewitched and Hazel, the latter winning Shirley Booth an Emmy and both contributing to Ackerman's reputation for attracting spectacular acting talent to the sitcoms.

"I have always derived a particular kick out of acquiring just the right performer for a given part," he says, "and I think that has had a great deal to do with the success of many of my series." When he first approached Booth's manager with the proposal to star her as everybody's favorite cartoon domestic, Ackerman recalls, the man was outraged at the suggestion, but the actress was delighted at the part. Even though Agnes Moorehead's Hollywood reputation was based solely on dramatic roles in movies, Ackerman recruited her as Endora, the witchy mother-in-law, because "I knew she was a superb commedienne, having cut my eyeteeth as associate producer of The Phil Baker Show, where Aggie was one of his three comedy stooges."

Ackerman went straight from Dartmouth into the advertising business, in the days when agencies actually produced entire programs for their client-sponsors. He directed the original LoneRanger and other such golden oldies as The Kate Smith Hour,The Aldrich Family, and Sceeen Guild Theatre, on his way to becoming Young & Rubicam's vice president for radio and television operations. He went to CBS in 1948 as executive producer, became vice president in charge of network programs, then turned down the presidency of CBS television to remain in production.

After leaving the network in 1956 to form his own company, Ackerman merged it two years later with Screen Gems, Columbia Pictures' TV subsidiary, which made him vice president and executive producer, with an interest in all the series he supervised. Two years ago he went independent again with Harry Ackerman Productions, a firm which produces and sells shows to the networks. Harry Ackerman Productions is currently working on a two-hour movie for ABC and a half-hour series called "You'reOnly Young Twice" for syndication.

Like any conscientious parent, Ackerman faces up to the family's frailties as well as its virtues. Network ownership of the medium, he charges, has had a "deleterious effect" on television, dulling innovation and creativity. "The principal thing wrong . . in my opinion," he says, "is that both series and TV movies are constructed to network-dictated formulas, which result in a deadened feeling of sameness with each season."

"In general, I don't think that commercial television has materially improved since the Newton Minnow 'wasteland' days," he laments, adding that, "I am not sure anything more can be done about bettering commercial television, which is almost totally an advertising-oriented force. What I look forward to with hope is the considerably widened choice of programming which will be available to viewers with the spread of cable systems."

Among his other attributes, Harry Ackerman is an iconoclast, ruinous to our firmly held image of show-biz executives as a parcel of egotistical cut-throats. Even TV's own offerings this year depict them as just as villainous as we had always known them to be. Then along comes Ackerman - a trustee of the Motion Picture and Television Relief Fund, a director of the Los Angeles Music Center, member of the original Hopkins Center Advisory Board - and spoils the whole thing. Not only that, but even his colleagues and co-workers have officially declared him a kind and gentle man. They were all there, 1,000 strong, at a vast love-in put on by the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters - Edgar Bergen and George Gobel; Jay North, Dennis grown up, and Eve (Miss Brooks) Arden; Fibber McGee and Elizabeth Montgomery (without the nose twitch). It's getting so you can't believe in anything any more.

But Ackerman collects more than kudos. He is a knowledgeable historian and renowned collector of letters and documents - relating particularly to the French and Indian Wars and the American Revolution - and of other memorabilia. He owns, for instance, President Lincoln's legal wallet and his pen knife, a letter complete with drawings by Paul Gauguin about Van Gogh's death, and a check written by Charles Lindbergh in payment for the Spirit of St. Louis. Youthful summers at the family cottage on Upper Lake George, New York, near Fort Ticonderoga, provided the initial stimulus for his fascination with American history, Ackerman says, and a holograph letter of Wilkie Collins, offered with a special edition of The Moonstone, started him collecting in earnest years ago in New York.

Unlike the medium he loves, Harry Ackerman and his productions - series and movies, six children ranging down to ten years of age, community enterprises, and the collector's enduring quest - seem unlikely ever to be afflicted by that "deadened feeling of sameness."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

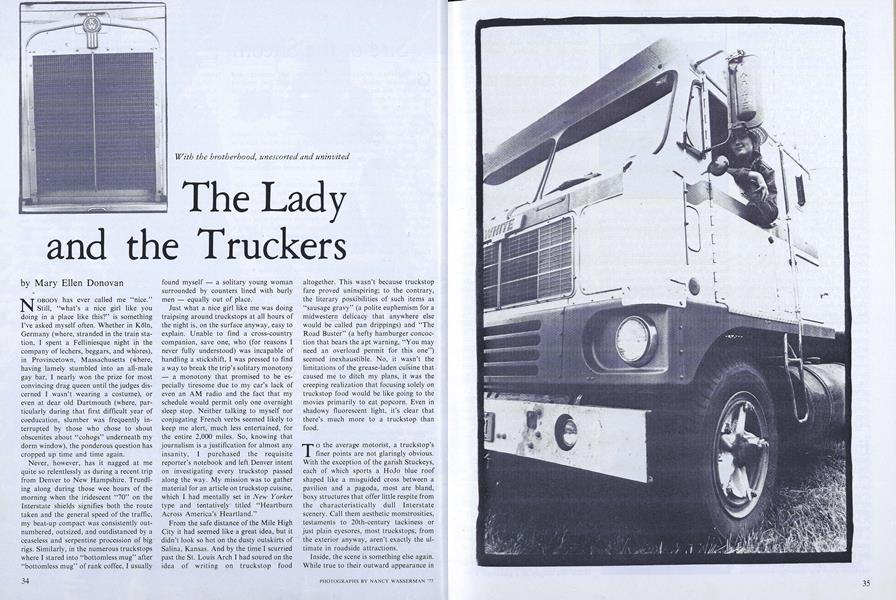

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

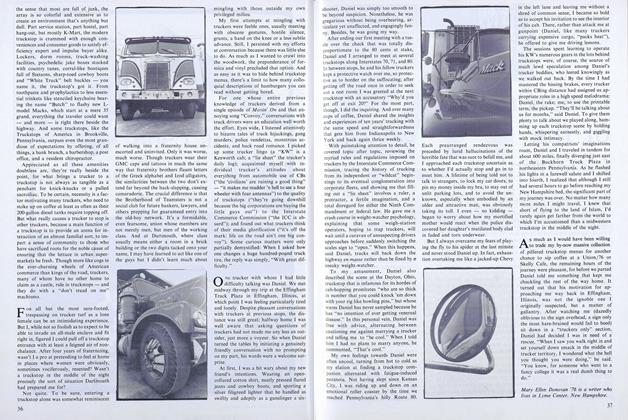

FeatureBeauty and the Beasts

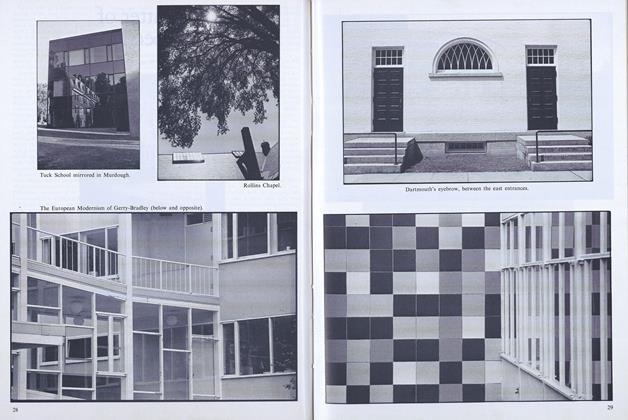

October 1978 By William Morgan -

Feature

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

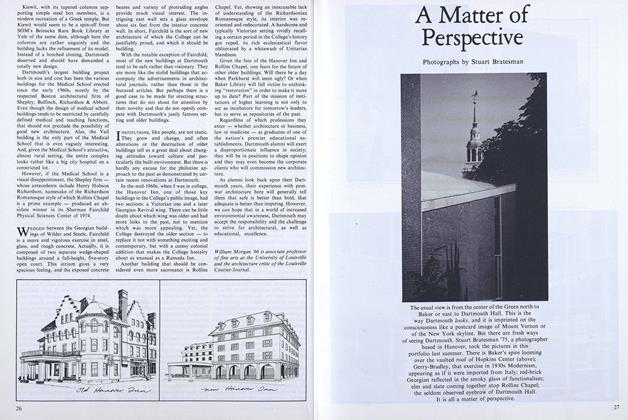

FeatureA Matter of Perspective

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

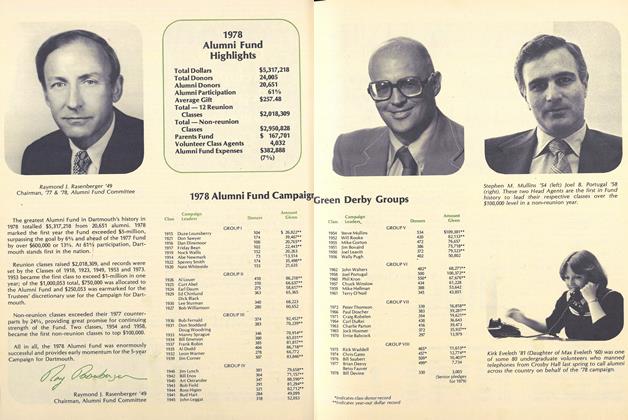

ArticleOffice of Development Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1978

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

APRIL 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleConservator by Design

February 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleM for Mystifier

March 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOf Ancient Mariners... and Monsters of the Deep

September 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

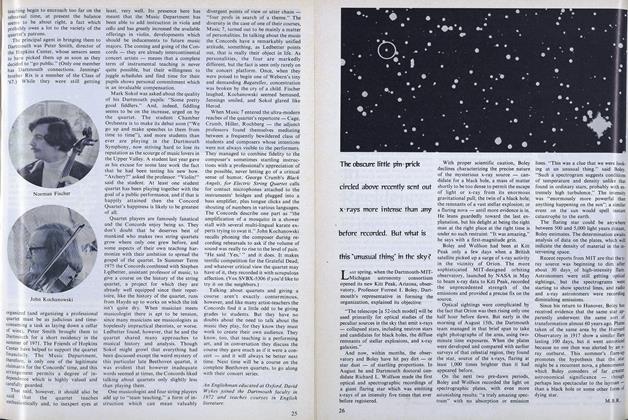

ArticleThe obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky?

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT TUCKER'S RESPONSE, ACCEPTING THE NEW DARTMOUTH HALL IN BEHALF OF THE TRUSTEES

AUGUST 1906 -

Article

ArticleAnother Dartmouth Club!

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1930 Endows Lectureship

APRIL 1972 -

Article

ArticleWayne Pirmann: Problem Solver

NOVEMBER 1970 By J.D. -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Clubs

January 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37